photo © Muhammad Ahmed, 2008

by Farah Ahamed

“If you find my stories dirty, the society you are living in is dirty. With my stories I only expose the truth.” ~ Saadat Hassan Manto

Saadat Hassan Manto was born in 1912 in the Punjab, British India. After the Partition in 1947, he migrated to Pakistan where he died in 1955. During his short life he produced twenty-two collections of short stories, one novel, five series of radio plays, three collections of essays, and two collections of personal sketches. He always wrote in Urdu but some of his most famous works have been translated into English. He is now considered to be one of the best short story writers from South Asia, and in 2015 a biographical drama film Manto was released celebrating his life and work.

Like D.H. Lawrence, to whom he has frequently been compared, Manto was a popular but also controversial character because of what he wrote about and the explicit nature of his language. His stories, usually satirical in tone and minimalist in style, were published at a time when both India and Pakistan were very conservative. They explore the taboo aspects of relationships such as sex and violence, and also depict the socio-political features of a culture that constrained and harmed both men and women. These were published in his series Letters to Uncle Sam and Nehru. Many of his writings were banned by both Indian and Pakistani governments for being unpalatable, but he continued to write in his own style about the darker aspects of life.

He started his literary career translating the works of Victor Hugo, Oscar Wilde, Chekov and Gorky, and their combined influence helped him locate his own writing. His first story, ‘Tamasha’, was based on the Jallianwala Bagh massacre at Amritsar. Though his earlier works tended towards leftist ideas, his later work is bleak in its depiction of the human psyche. He wrote of himself:

Manto … runs off from fragrance, chasing filth. He hates the bright sun, preferring dark labyrinths. He has nothing but contempt for modesty but is fascinated by the naked and the shameless. He hates what is sweet, but will give his life to sample what is bitter. He does not so much as look at housewives but is entranced by the company of whores. He will not go near running waters, but loves to wade through slush. Where others weep, he laughs; where they laugh, he weeps. Evil-blackened faces he loves to wash with tender care to highlight their features.

In 1945, Manto’s stories ‘Kali Shalwar’, ‘Dhuan’ and ‘Bu’ were tried under Section 292 of the Indian Penal Court and, although he was acquitted from both cases, he felt misunderstood and humiliated. This sense of isolation increased throughout his life.

In 1945, Manto’s stories ‘Kali Shalwar’, ‘Dhuan’ and ‘Bu’ were tried under Section 292 of the Indian Penal Court and, although he was acquitted from both cases, he felt misunderstood and humiliated. This sense of isolation increased throughout his life.

In 1948, he produced a film in Bombay based on the life of the nineteenth Century Urdu poet Mirza Ghalib, which later won a National Award. However, before the film was completed, and against the advice of colleagues who believed he would thrive in India, Manto decided to move to Pakistan due to the insecurity he felt as a Muslim after the Partition. His anxiety and restlessness worsened as he discovered that the landscape of Lahore that he had known pre-independence no longer existed. Again, he felt like an outsider. Lahore was in a state of turmoil following the influx of hundreds of thousands of refugees arriving in a state of destitution after surviving the long trek, only to discover that the government had made no provisions for food, or shelter. Aside from the lack of humanity from the State and those around him, Manto also found that the ruling class in Pakistan was moving to an interpretation of Islam, which was, to his mind, hypocritical and insincere.

Like his favourite poet Ghalib, Manto was an alcoholic gambler and a spendthrift. When his wife had him admitted to a mental institution in Lahore for treatment, it was the biggest blow of his life. “I feel like I am always the one tearing everything up and forever sewing it back together,” he said. This idea of devastation and the struggle for reconstitution is apparent in his stories where he strives for literary effect, not through a grand narrative arc but through a simple narration of a series of small incidents. His characters are not defined by the way they look, but by their actions in the present moment. His descriptions are not sensory observations but rather unsentimentally observed settings for particular events. He wrote:

For me, remembrance of things past has always been a waste of time, and what’s the point of tears? I don’t know. I’ve always been focussed on today. Yesterday and tomorrow hold no interest for me. What had to happen, did, and what will happen, will.

This ever-present sense of fatality and impotency in the face of larger events, combined with the trajectory of his own life, colours all his writings.

After Manto was released from the mental institute he wrote ‘Toba Tek Singh’, which is considered his masterpiece. It was published in Phundne in the year of his death and several English translations are available. The story is told from an omniscient point of view in a dead-pan tone as the narrator describes darkly comic events that culminate in a tragedy. The story illustrates the activities of lunatics in a Lahore asylum and is a satire and an indictment of the political systems and processes that produced the Partition; it opens:

Two or three years after the Partition, it occurred to the governments of India and Pakistan that, along with the transfer of the civilian prisoners, a transfer of inmates of the lunatic asylums should also be made. In other words, Muslim lunatics from Indian institutions should be sent over to Pakistan, and Hindu and Sikh lunatics from Pakistani asylums should be allowed to go to India.

The story is not told chronologically. The first two paragraphs are about the exchanges taking place at the Wagah border, where the inmates are waiting to be transferred. The story flashes back to the moment when the inmates were first told about the proposed exchange and then, in the closing scene, moves back to the border again. The narrator says the inmates ‘did not have all the facts’, the guards are ‘illiterate’, and every one, deranged or not, has to obey a higher authority. The inmates do not know where Pakistan is, or where its boundaries are, and they know of the country’s founder, Jinnah, only in passing. The disorientation of the mad men is heightened by the question of whether they are in India or Pakistan, and if they had been in Pakistan, how is it that they are in India now when they had not moved from the asylum at all. Manto describes the encounters between the inmates, their conversations and actions, including a man stripping off his clothes in protest because his lover lives across the new border, and the feeling of abandonment by two Anglo Indians who realise the British have left India.

The main character is Bishan Singh, an inmate from the Toba Tek Singh district, in the Punjab province of Pakistan. Bishan was brought to the asylum fifteen years earlier, in iron chains, when he suddenly went mad. His family used to visit him regularly, even though he hardly spoke to them, but since the Partition their visits have stopped and Bishan Singh’s condition deteriorates. He is desperate to know if Toba Tek Singh, where he owned a piece of land, is now in India or Pakistan. He asks everyone he can this question, in a barely intelligible string of gibberish. One Muslim inmate, who believes he is God, tells him he is too busy to answer him. Bishan is visited by an old Muslim friend and he asks him the same question, but his friend is at a loss too, and this enhances Bishan’s despair. This is all just a few days prior to the transfer.

In the final part of the story, the lists of patients are exchanged between the two sides, and lorries packed with inmates are sent to the border at Wagah. There, Bishan Singh asks one of the officials, “Where is Toba Tek Singh?” “Pakistan,” the officer laughs. On hearing this Bishan tries to escape and runs off. He is captured by the soldiers and forcibly returned to the checkpoint. He is then told Toba Tek is in India. But Bishan Singh is adamant and protests incomprehensibly that he must know for sure before he goes anywhere. So he stays on one spot between the wired fence borders of Pakistan and India ‘as if no power in the world could move him’, and before day break he lets out a cry and dies ‘in the middle, on a stretch of land that had no name’.

In the final part of the story, the lists of patients are exchanged between the two sides, and lorries packed with inmates are sent to the border at Wagah. There, Bishan Singh asks one of the officials, “Where is Toba Tek Singh?” “Pakistan,” the officer laughs. On hearing this Bishan tries to escape and runs off. He is captured by the soldiers and forcibly returned to the checkpoint. He is then told Toba Tek is in India. But Bishan Singh is adamant and protests incomprehensibly that he must know for sure before he goes anywhere. So he stays on one spot between the wired fence borders of Pakistan and India ‘as if no power in the world could move him’, and before day break he lets out a cry and dies ‘in the middle, on a stretch of land that had no name’.

The themes of ownership, belonging, migration, national identity, statelessness, family and home are at the core of the story, alongside a critique of the political and administrative structures of inhumane governments. The story reflects Manto’s own struggles and sense of impotency in the face of these forces. The biting satire shows not just the impression the asylum had on him, but also his realisation of the collective madness around him. The sense of isolation and cynical view of society reflected in his writing was heightened by his numerous court cases, reproaches and cultural alienation. In ‘Why I Write Essays’, he wrote:

…I thought a glass of lassi would be refreshing. In the shop I noticed the fan was on, but turned away from both customers and the owner. I asked why it was so. The owner glared and said: ‘Can’t you see?’ I looked. The fan was pointed in the direction of a poster of our great leader, Muhammad Ali Jinnah. I shouted, ‘Pakistan Zindabad!’ and left without the lassi…

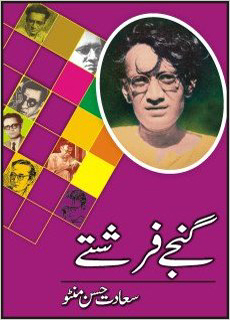

In Pakistan, while Manto was at his most creative, he was also under extreme financial pressure to make a living from his writing. The only paper that published his articles regularly was Daily Afaq where he contributed accurate sketches of Pakistani actors and literary figures which were later compiled in his book Ganjay Farishtay (Bald Angels). Some of his writings from that period are also the most eloquent and scathing critiques of the Transition. In 1950, he wrote the short story ‘Thanda Gosht’, based on the communal violence he had witnessed. It was immediately banned by the Pakistani government and he was sentenced to imprisonment and fined. Two more of his stories about violence against women, and a farce about a couple’s attitude towards sex, were also charged with being obscene. In his writings, he refused to turn away from any aspect of humanity or life, whether tragic or comic. He told the stories of prostitutes and pimps, highlighted the use of violence against women and drew attention to their sexual slavery.

Towards the end of his life, Manto grew more restless and, like the characters in Toba Tek Singh, he felt an acute sense of both real and figurative displacement and dislocation. In his notes he wrote:

…the bitter truth is that so far I have failed to find a place for myself … that is why I am always restless … that’s why sometimes you find me in a lunatic asylum, other times in a hospital. I have yet to find a niche…

At a time when borders have electric fences, and refugees are fleeing in their thousands, Manto’s ‘Toba Tek Singh’ has particular relevance and poignancy.