photo © Tony Armstrong, 2015

by Sophie Reid

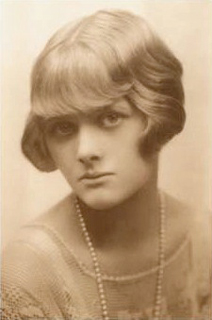

Dame Daphne du Maurier was born in 1907 and started her writing life with short stories. Her first published story, ‘And Now to God the Father’, came out in 1929 in The Bystander. After publishing her first novel, The Loving Spirit, in 1931, du Maurier moved to Cornwall, staying there until her death in 1989. The county was the inspiration behind many of her most famous books. During her lifetime, du Maurier published six short story collections, as well as seventeen novels and several non-fiction works.

I first discovered du Maurier through her novels, but her short stories offered something different to me as a young reader. As good short stories should, they deliver complete worlds, ask questions, and leave you wanting more. Many explore themes of what it is to be human, the darkness in our minds, and the darker sides of life.

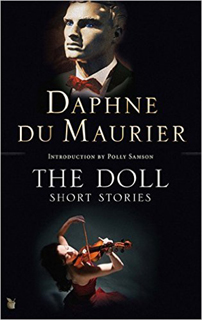

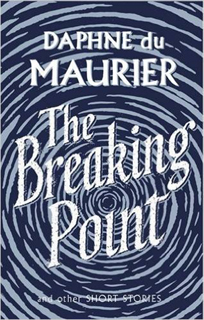

Over the years, du Maurier has experienced a resurgence in popularity thanks to Virago Books reprinting her backlist, including non-fiction and short stories. When I started reading her work, only Rebecca was readily available in print. Now, her writing is studied at universities, dramatised for TV, and discussed all over the world. There have even been new collections published, consisting of rediscovered short stories: The Breaking Point and Other Stories (2009), and The Doll: Short Stories (2011), which includes her earliest published works.

Over the years, du Maurier has experienced a resurgence in popularity thanks to Virago Books reprinting her backlist, including non-fiction and short stories. When I started reading her work, only Rebecca was readily available in print. Now, her writing is studied at universities, dramatised for TV, and discussed all over the world. There have even been new collections published, consisting of rediscovered short stories: The Breaking Point and Other Stories (2009), and The Doll: Short Stories (2011), which includes her earliest published works.

On rereading the stories, I find myself lost in the foreboding and unsettling world that du Maurier inhabits. Her writing is dark and much of the subject matter twisted. Nothing quite turns out as you expect. Her short stories showcase this more acutely than her novels: the limited space available seems to have allowed her to play with forms and ideas, which she later translated to her longer works.

‘The Happy Valley’, first published in 1932 and recently reprinted in The Doll: Short Stories, contains some of the themes and locations used later in Rebecca. The dream-like state that the main character finds herself in seems to echo the dreams of the second Mrs de Winter, who dreams of Manderley and the house left to ruin. The story opens with the character dreaming of the happy valley:

…she would find herself walking down a path, flanked on either side by tall beech trees, and then the path would narrow to a scrappy muddy footway, tangled and over-grown, with only shrubs about her – rhododendron, azalea, and hydrangea, stretching tentacles across the pathway to imprison her.

To readers familiar with Rebecca, these dreamlike images are recognisable. It is clear that these early stories helped lay the groundwork for future novels, planting seeds in du Maurier’s brain, enabling her to see what worked, and what didn’t. Polly Samson, in the introduction to The Doll, writes of these early stories:

…heartless males and hapless females dictate that there are to be no happy endings, show[s] a clear-eyed young mind with scant faith in the possibilities of love and marriage.

This persists throughout du Maurier’s work; there is rarely a happy ending: the women are often helpless, and the men brutal and self-obsessed.

This persists throughout du Maurier’s work; there is rarely a happy ending: the women are often helpless, and the men brutal and self-obsessed.

Many of du Maurier’s short stories stick in my mind for their uncanny themes: ‘The Apple Tree’ sees a widower believe that the spirit of his late, neglected wife is trapped in an apple tree; ‘The Pool’ evokes puberty in a secret, magical world; the main character of ‘The Blue Lenses’, Marda West, after eye surgery, sees those around her in the animal form that represents their true nature. As she realises that it isn’t a prank played on her by the doctors and nurses, Marda grows unsettled.

No, they could not be wearing masks. The kitten’s surprise and resentment had been too genuine. And the staff of the hospital could not possibly put on such an act for one patient, for Marda West alone – the expense would be too great. The fault must lie in the lenses, then. The lenses, by their very nature, by some quality beyond the layman’s understanding, must transform the person who was perceived through them.

The surprise and unease of the character makes for unsettling reading. It seems clear that the lenses are at fault, but then how and why? What the character sees through them is a reflection of the true nature of the characters around her and, as a reader, this makes you stop and consider those around you.

The Breaking Point and Other Stories, the collection that includes ‘The Blue Lenses’, contains stories that were written at a time in du Maurier’s life when she was under great stress due to her husband’s breakdown. In her introduction to the collection, Sally Beauman writes:

The stories here reflect and echo that psychological stress, it runs through them like a fault line […] these stories are jagged and unstable; they constantly threaten and alarm; they tip towards the unpredictability of fairy tale, then abruptly veer toward nightmare. They are elliptic, awkward – and they are fascinating.

It is clear that du Maurier didn’t write fairy tales; she wrote stories that get under your skin. She is an author you think you know – thanks to the enduring popularity of Rebecca, Jamaica Inn, and Frenchman’s Creek – and often, both author and work are wrongly dismissed as ‘romantic’. And yet, there’s something different in her short stories, something that makes you stop, gasp, and puzzle over the thread of the story; something that makes you want to go back to the start and read it again. They’re uncomfortable, and in their pages du Maurier shows that she is anything but a romantic novelist.

It is clear that du Maurier didn’t write fairy tales; she wrote stories that get under your skin. She is an author you think you know – thanks to the enduring popularity of Rebecca, Jamaica Inn, and Frenchman’s Creek – and often, both author and work are wrongly dismissed as ‘romantic’. And yet, there’s something different in her short stories, something that makes you stop, gasp, and puzzle over the thread of the story; something that makes you want to go back to the start and read it again. They’re uncomfortable, and in their pages du Maurier shows that she is anything but a romantic novelist.

On writing these stories, du Maurier, in her letters to Oriel Malet, published as Letters from Menabilly in 1992, referred to intense periods of ‘brewing’ the stories and letting them form in her mind, before committing them to paper. Reflecting on one story, ‘Borderline Case’, du Maurier wrote:

…it’s rather an awful story really. The end, I mean. My next story, ‘The Way of the Cross’ will be the most difficult. The Jerusalem one, a bunch of people who all find their cross when they get there.

These stories were published in a collection alongside ‘Don’t Look Now’ in 1971, entitled Not After Midnight. The insights into the workings of du Maurier’s writing suggest the amount of work and thought she put into each individual story, as well as the length of time taken to create each one.

Sadly, although her novels are widely known and loved, du Maurier is not remembered for her short story collections. Of them, only ‘The Birds’ and ‘Don’t Look Now’ really remain in the wider public consciousness, made famous by the horror films (directed by Alfred Hitchcock and Nicolas Roeg, respectively), and few people are aware of the fact that both of these started life as short fictions.

Du Maurier’s writing has followed me for most of my life. When, at the age of thirteen, I discovered Rebecca, I was drawn into her world, devouring every piece she had written – from novels and short stories to plays and biography. Her short stories, in particular, have had a great impact on my own writing: they are a masterclass in unsettling your readers and their expectations. As I’ve grown older and gone back, time and time again to du Maurier’s work, I find that there is something different in the stories on each reading, something that makes me look at the world in a different way, and to reconsider what I think I know. Her writing makes me look under the surface and into the depths, and each time I return, I’ve changed a little.