photo crop © Carly Lyddiard, 2012

*

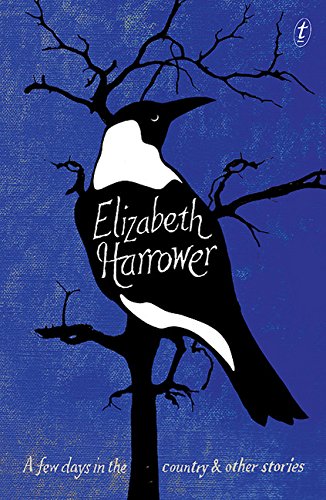

In this longlisted essay from the 2016 THRESHOLDS Feature Writing Competition, Nicole Mansour appreciates the murkier side of Australia in Elizabeth Harrower’s A Few Days in the Country.

~

Beyond the Barren Landscape

by Nicole Mansour

Australia: a vast island continent, composed of remote red desert bathed in endless sunshine, edged by countless miles of golden beaches, tinted with the honey-pine scent of eucalyptus, the morning laugh of kookaburras.

Aside from Australia’s colonial heritage and the ancient traditions of our indigenous peoples, it is the images of sunshine and coast, desert and rainforest, that are most often burned into the retina of anyone gazing too long into the sundrenched archives of Australia’s cultural past. One would be forgiven for remembering only the squinty-eyed larrikins, the Aussie battlers and bushrangers of an earlier, more dangerous time; they’d be further excused for remaining unaware of a murkiness, an opacity, so often concealed – though never lost – beneath an ever-glaring sun. Few Australian writers, in my opinion, traverse these dim corners of ambiguity, or unearth this more uncommon caliginosity from far beneath its exterior, in either their characters or their writing – Murray Bail and Gerard Murnane are notable exceptions. Elizabeth Harrower is another.

Harrower’s recent short story collection, A Few Days in the Country, is a fine reflection of an old-fashioned Australia, of an amiable but sometimes dim middle-class, of loneliness and melancholy, and of people with a quiet desire to linger among the shadows.

Born in Sydney in 1928, Elizabeth Harrower began writing after she moved to London in 1951. Her first novels were published upon her return to Australia during the late 1950s, and most of the short stories in this collection – or at least versions of them – were written during the 1960s.

Now, decades later, Harrower is finding international critical acclaim, much of it the result of her novel In Certain Circles. This was also written in the 1960s, but withdrawn from publication by Harrower at the last moment. When the novel was eventually published in 2014, a shining review by James Wood in The New Yorker garnered Harrower a revival of adoration that was sadly long overdue, both at home and abroad.

Now, decades later, Harrower is finding international critical acclaim, much of it the result of her novel In Certain Circles. This was also written in the 1960s, but withdrawn from publication by Harrower at the last moment. When the novel was eventually published in 2014, a shining review by James Wood in The New Yorker garnered Harrower a revival of adoration that was sadly long overdue, both at home and abroad.

A Few Days in the Country is a small but compelling collection of short fiction that brings together twelve stories that invoke images of mid-twentieth century Australia: small-minded, middle-class Australians, marginally wary of foreigners, still inexorably linked to the ‘old country’. But the stories also challenge these images, daring to excavate below the surfaces of sand and sunshine. Full of sharp, social observation, her stories have a gentle meanness and a cutting irony; they are full of lonely women, and intolerant men, of characters longing for a world beyond the brightly lit one in which they are living.

In the opening story, ‘The Fun at the Fair’, a young girl is taken to the fairground by her uncle and his girlfriend, only to discover the emptiness of human relationships. Disappointment with relationships is also a theme in ‘Alice’, in which the title character endures a lifetime of feeling inferior, due to both her mother’s lack of affection and her husband’s infidelity. It is not until an unexpected encounter with a young bride that Alice finally discovers the possibility of acceptance and change.

Oh, but she wished, she wished there were someone she could tell. Then, in the middle of this tremendous wish, Alice paused: a great thing was beginning to happen to her. A new thought appeared in her mind, yet Alice recognised it as if it had always been there. The thought said, But I know. I know.

After this she looked the same, and her circumstances didn’t alter, but she was a different person altogether.

The two young women in ‘The City at Night’ fare better, finding friendship as an unexpected consequence of their confessions of loneliness. And in ‘English Lesson’, an undefined insult, and the almost intolerable hurt pride that results, leads Laura to a moment of epiphany and self-enlightenment.

The closing, title story, ‘A Few Days in the Country’, is perhaps the most deeply psychological of the collection. Here, the protagonist, a pianist named Sophie, unexpectedly finds herself accepting an invitation to stay at her acquaintance’s country house. She blames an uncharacteristic impulse to escape Sydney living: ‘Suddenly the city just– got me down.’ Sophie’s pensiveness lingers throughout the narrative, as she meditates on life, human behaviour, and suicide.

It was unanswerably true that she had placed herself in the hands of death; she was in the airy halls of death now, with all formalities complete except the last one. Everywhere there was the certainty, the expectation, that she would make the final move at any moment. And it was so clear that the alternative to death was something worse.

In the end, Sophie finds herself at the train station embarking upon her return journey to the city, still haunted by thoughts of death, but with a resilience that remains undaunted.

But of all Harrower’s tales, it was ‘The Beautiful Climate’ that resonated with me most of all. It tells the story of eighteen-year-old Del Shaw who, together with her docile mother, obediently follows the instruction of the unpredictable and domineering Hector Shaw. The family spend their weekends at a seaside cottage that Mr Shaw has recently purchased and which, later, he independently contrives to renovate and sell. He promises the two women that the sale of the cottage will finance a voyage to Europe, to the ‘old country’, but, when the cottage still hasn’t sold after six months, Del becomes doubtful of the intended journey, and the subsequent liberation from her stifling family she hopes it will offer.

But of all Harrower’s tales, it was ‘The Beautiful Climate’ that resonated with me most of all. It tells the story of eighteen-year-old Del Shaw who, together with her docile mother, obediently follows the instruction of the unpredictable and domineering Hector Shaw. The family spend their weekends at a seaside cottage that Mr Shaw has recently purchased and which, later, he independently contrives to renovate and sell. He promises the two women that the sale of the cottage will finance a voyage to Europe, to the ‘old country’, but, when the cottage still hasn’t sold after six months, Del becomes doubtful of the intended journey, and the subsequent liberation from her stifling family she hopes it will offer.

She lay in a deckchair on the deserted side veranda and read in the mellow three o’clock, four o’clock sunshine. There was, eternally, the smell of grass and burning bush, and the homely noise of dishes floating up from someone’s kitchen along the path of yellow earth, hidden by trees. And she hated the chair, the mould-spotted book, the sun, the smells, the sounds, her supine self.

They came unto a land in which it seemed always afternoon.

“It’s like us, exactly like us and this place,” she said to her mother, fiercely brushing her long brown hair in front of the dressing table’s wavy mirror. “Always afternoon. Everyone lolling about. Nobody doing anything.”

This evocation of languid emptiness, and Del’s frustration at being unable to evade its sultriness and confinement, echo my own feelings and experiences: it’s as if the possibility of creating something valuable seems insurmountable in the face of such a bare, repressive, and remote landscape; departure offers a promise of something left unfulfilled by sea and sunshine.

For most of my adult life I have undertaken to live outside of Australia. During those years when I have inhabited Sydney (like Harrower’s, my home town) or Melbourne, I have yearned to live elsewhere. Always have I blamed this longing for dissent on my country’s seeming lack of culture, the emptiness perpetually evoked by its barren landscape, its ‘mateship’ sensibility. I have a dubious memory of overhearing Australian author Murray Bail once describe our homeland – while sitting in an Italian café in inner Sydney – as ‘too thin, too brightly lit’. Those words have remained with me over the years, both in and away from Australia. Inarguably, they capture something of my country’s youth, its apparent vacuity, its immutable glare. Of course, it is always easier to criticise than to praise, and the grass is perpetually greener on the other side of the fence.

One might conceivably experience Harrower’s stories as domestic nuance, as simply depicting a small corner of Australia’s past, and, in many ways, this perception may be true. But it is the way in which Harrower executes her characters and their landscapes, their complexities and isolation that makes her writing so compelling. There is an unsettling truth in her work that seems to unearth something deeper and more ambiguous, perhaps even sinister, lurking underneath the obvious radiance and illusive triviality. It may be difficult to catch sight of under the dazzling noon-day sun, but as the afternoon rolls on into evening, and those cloudless blue skies fade to peach, you may find yourself catching sight of something more capacious hovering in the shade of a Moreton Bay fig tree. And suddenly that barren landscape doesn’t seem so empty after all.

~

Originally from Sydney, Nicole Mansour is a graduate of the Actors Centre Australia and is currently completing a BA in literature. She is a former inhabitant of Buenos Aires, London, Melbourne and Hong Kong, an occasional visitor to Japan and New Zealand, and was once a tourist in New York; in all these places (and others) she has taken many photographs (on film) and written fragments of stories (as yet unpublished). Like Susan Sontag, she loves to read the way other people love to watch television.

Originally from Sydney, Nicole Mansour is a graduate of the Actors Centre Australia and is currently completing a BA in literature. She is a former inhabitant of Buenos Aires, London, Melbourne and Hong Kong, an occasional visitor to Japan and New Zealand, and was once a tourist in New York; in all these places (and others) she has taken many photographs (on film) and written fragments of stories (as yet unpublished). Like Susan Sontag, she loves to read the way other people love to watch television.