photo © tomy pelluz, 2005

by C. D. Rose

I’m in a second-hand bookshop somewhere. I bend down before over-stacked shelves high-piled with broken-spined paperbacks that smell of sadness. I’ve developed quite an eye over the years, rapidly able to discern wheat, chaff and everything in between and, while my eyes scan the shelves, I pick out something unusual: a thin white spine, on it a few words in orange caps, And Other Stories. Immediately, I think there’s something wrong here, something must be missing. So I lean forward and slip the book from the shelf.

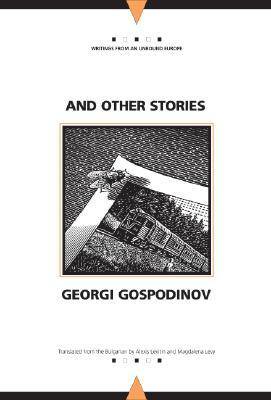

No mistake – this book is called nothing more than And Other Stories. Written by someone I have never heard of, and whose alliterative name seems initially unpronounceable: Georgi Gospodinov.

There’s a single picture on the black and white cover, a drawing of a photograph of a train (with a fly on it – the reasons for the fly become only obvious much later in the reading of the book). I am obsessed by stories about trains, and by stories about photographs. I feel strangely chosen. A few minutes later, and a mere 75p lighter, I take the book home, make a pot of tea and start on my find.

The first story, ‘Peonies and Forget-Me-Nots’, takes less than a few minutes to read, but encompasses lifetimes. A man and woman meet by chance at an airport, only a few hours before her departing flight. They know immediately that they are destined:

He thought that he would never meet another woman like this one, who would be capable of reading his thoughts, with whom he would want to spend the rest of his life in this café.

And, yes, she feels the same way. They have too little time to waste ‘in beating around the bush and making boats’, so rapidly invent their entire lives together, what they have been, and what they will be. Two pages and fifty years later, she leaves and he sees his reflection in a glass door, ‘his hair turned suddenly white and those stooped shoulders of an old man’.

And, yes, she feels the same way. They have too little time to waste ‘in beating around the bush and making boats’, so rapidly invent their entire lives together, what they have been, and what they will be. Two pages and fifty years later, she leaves and he sees his reflection in a glass door, ‘his hair turned suddenly white and those stooped shoulders of an old man’.

It is one of the most perfect stories I have ever read, doing exactly what a short story can do best, and what only a short story can do: encapsulate lifetimes in minutes. In three pages, Gospodinov has pulled my heart out, reconfigured it, and stuffed it back.

I turn the page, realising how my afternoon will now be spent, and read the second story. It’s called ‘A Second Story’. A man meets a woman on a train and starts to tell her a story in order to impress her. As he tells the story, the woman seems both attentive, yet curiously disengaged. It matters little, as the narrator loves his tale so much he goes ahead with it – it is a story that his grandfather told, an incident that had happened to him on a train involving a Bulgarian and a Hungarian, misrecognition, smoking and lingusitic confusion – and then, at the end, the woman responds. Her line, one line only, is both utterly crushing, absolutely hilarious and reflects on the tale the narrator has told perfectly.

No, I’m afraid I can’t repeat it. You have to be there.

What I will say is that I usually mistrust twists in the tail, cheap narrative turns, stories that only mean something when you get to their last line. But Gospodinov is aware of this, and takes the whole reason why you’ve felt cheated by such stories so many times in the past into account, and accounts for that too. That’s why the line is so strong.

My tea has gone cold by now so I make another pot and start Googling. While I am a fan of neglected classics, the forgotten, lost and obscure, Georgi Gospodinov’s And Other Stories turns out to be not as obscure as I expected. Gospodinov, I find, is a well-respected Bulgarian writer, author of a novel called Natural Novel, in his late-forties, prize-winning, widely-translated. I curse the narrowness of the Anglo-Saxon reading world, switch the computer off, and read on. I love this book even more, already, only two stories in.

I rarely read short story collections in one go. But this book compels me. Perhaps it is the brevity of each of the pieces – the longest, ‘Gaustine’, stretches to an epic seven pages – most of which have the length of a long breath, that draws me to turn the page and begin again. A few hours later, I too am fifty years older.

I rarely read short story collections in one go. But this book compels me. Perhaps it is the brevity of each of the pieces – the longest, ‘Gaustine’, stretches to an epic seven pages – most of which have the length of a long breath, that draws me to turn the page and begin again. A few hours later, I too am fifty years older.

These stories, edited to the quick, leaving only the raw stump of what tales are, contain multitudes. Gospodinov deftly uses the whole gamut of narrative devices – framing situations, boxes-within-boxes, digressions and regressions – to make each tale hold far more than a few pages could reasonably seem to take.

‘The Eighth Night’ begins: ‘One night his great-grandfather took his sheep to graze far away from the village, in a sheltered clearing near a grove.’ So far, so Bulgarian-short story. But it then veers away to describe a series of lectures given by Borges, reflections on what deafness might mean, and how a story may be remembered, or forgotten. It ends far from the sheltered clearing of the first line.

‘Blind Vashya’ is the story of a woman who is not blind at all, but who can see the past through her left eye, and the future through her right one. This parable about memory and knowing feels ancient – on first reading, I felt I knew this story already – yet utterly modern at the same time. Its precise, paratactic prose – ‘Vasha was blind. Everybody called her Blind Vasha. She barely left her house’ – averse to adjectives, works so hard that a simple mention of cherry trees and blackberry bushes gives a huge splash of colour. Its cadence is that of an expert storyteller reciting an oft-told tale, the rhythm of the words marked out by the teller over time. It ends with a direct address: ‘And if you, the reader of this story…’ – a device which, again, is very postmodern, yet also bringing us back to that village sage imparting difficult wisdom.

In ‘The White Pants of History’ Gospodinov takes something as simple and as basic as a bar-room tale and uses it to illuminate the course of European history: the narrator’s father washes his underpants, and finds himself engaged by opposing militia. These stories are all rooted in the told tale, the overheard conversation, an anecdote or joke. They have a postmodern knowingness, a knowingness rooted in the fact that they are pre-modern. They are supremely self-aware – often, the narrator halts the narrative to point out where you have been, where you are, and where you are going. And they manage to conjure the voice of the teller in a way that is almost uncanny – in part, this is thanks to the wonderful translation by Alexis Levitin and Magdalena Levy.

Were this story perfect, I would have found this book on a train heading from one nowhere town to another, or it would have been gifted to me by a stranger met in a bar somewhere in Bulgaria. Yet finding it by chance in a shop filled with the detritus of other people’s lives is almost as apt. Such is the best home of so many stories.

~

C. D. Rose is the editor of The Biographical Dictionary of Literary Failure (Melville House), and author of ‘Arkady Who Couldn’t See and Artem Who Couldn’t Hear’ (Galley Beggar Singles) and ‘The Neva Star’ (Daunt). He is currently studying for a PhD in the short story at Edge Hill University.