photo © Antoine Robiez, 2013

by Aimee Gasston

Elizabeth Bowen, born in Dublin in 1899 and keeping pace with the twentieth-century as it progressed until her death in 1973, was an extraordinary writer. Or, as Hermione Lee put it in her 1999 ‘estimation’ of Elizabeth Bowen, ‘one of the greatest writers of fiction in this language and in this century’. As an English undergraduate at the University of East Anglia, I was lucky enough to be taught Bowen’s novel The Heat of the Day on a course about Blitz literature, alongside Patrick Hamilton and Graham Greene. But, despite her formal experimentation, she was never taught alongside the experimental modernist canon and, when I took an MA in Modernism, Bowen was nowhere to be seen either. As a practising writer, Bowen was compared with her contemporaries Virginia Woolf and Katherine Mansfield, as well as more historical heavyweights, Jane Austen and George Eliot. This reputation is not widely sustained today and this peculiarity is likely linked to the strangeness of her fiction. Because Bowen’s writing does not come with the caveat of (culturally-improving) complexity implicit to the work of Kafka, Beckett, Joyce and Woolf, it is possible that readers have felt ambushed, even assaulted, by the effort her rich sentences demand, and have beaten a bemused retreat.

It is not only her literary style that is extraordinary, but also her literary subjects, which often verge on the supernatural. Reading through Bowen’s collected short fiction, you will find ghosts, crimes and hauntings. There are hauntings that are paranormal as well as those which more abstractly explore the past’s moulding of the present. In a lecture given at the Unterberg Poetry Center in New York, in 1954, Bowen said ‘[t]he world is haunted and insecure’ – it is this world that all her writings reflect, but perhaps especially so her stories which naturally operate within the terrain of the liminal, rather like their Anglo-Irish creator. Looking back at her collection The Demon Lover and Other Stories from 1945, Bowen described the way in which the stories were written almost of their own volition, admitting them to be ‘[o]dd enough in their way’ and some ‘very odd’ (Collected Impressions, 1950). She almost suggests that these stories are ghosted in their own way, perhaps written by a haunted glove similar to that which featured in the 1952 story ‘Hand in Glove’.

Elizabeth Bowen’s commitment to the short story was extraordinary. Best known for her novels, she has said, according to Lee, that she would give up any of these for her short stories. I do not know of another novelist who holds the short form in such deservedly high esteem. Her introduction to The Faber Book of Modern Short Stories is frequently quoted with good reason – it is as salient an introduction to twentieth-century short fiction as one could hope for. In this essay she highlights the affinities between short fiction and the cinema, seeing each of these new art forms as an ‘affair of the reflexes, of immediate susceptibility, of associations not examined by reason’ and sharing a number of formal innovations. She posits the overriding objective of the short form as ‘necessariness’ and believed it should share an essence of feeling crystallised in style also found in poetry, that ‘valid central emotion of inner spontaneity of the lyric’.

Elizabeth Bowen’s commitment to the short story was extraordinary. Best known for her novels, she has said, according to Lee, that she would give up any of these for her short stories. I do not know of another novelist who holds the short form in such deservedly high esteem. Her introduction to The Faber Book of Modern Short Stories is frequently quoted with good reason – it is as salient an introduction to twentieth-century short fiction as one could hope for. In this essay she highlights the affinities between short fiction and the cinema, seeing each of these new art forms as an ‘affair of the reflexes, of immediate susceptibility, of associations not examined by reason’ and sharing a number of formal innovations. She posits the overriding objective of the short form as ‘necessariness’ and believed it should share an essence of feeling crystallised in style also found in poetry, that ‘valid central emotion of inner spontaneity of the lyric’.

Elizabeth Bowen’s sense of vision and form was extraordinary. She believed that the short story should be ‘composed, in the plastic sense, and as visual as a picture’. Before she became a writer, Bowen planned to be a painter, attending the LCC School of Art in London’s Southampton Row for two years at the age of twenty, and she would later maintain the best of her writing to be ‘verbal painting’, as noted by Victoria Glendinning, in Elizabeth Bowen: Portrait of a Writer. Even early stories, such as ‘The Contessina’ from 1926, bear this hallmark, offering voluptuous visual feasts throughout:

The sun was going down, the lake was of liquid flame with great cold blue shadows like swords stabbing across it. The hills were blue and sharp, the air crystal. The sleek oars swung and dipped to their reflections rhythmically […] The level sunshine crept along the air and brimmed with gold the little dints of mirth and pleasure in the Contessina’s cheeks, and drew a curve of gold along the brim of her hat.

This piece brims over itself, bursting giddily with sensuous surface detail tempered by the starker, bathetic threat of physical sexuality or violence ominously suggested by the sword-like shadows. The repetition of the word ‘brim’ in the context of the Contessina’s hat reminds us of its meaning as brink or periphery – many of Bowen’s stories deal with characters who are marginalised in some way, or otherwise ‘on the edge’, for example, Hermione in ‘The Easter Egg Party’ who ‘sat in the glass dome of her own inside world, just too composedly’, or the deaf Queenie in ‘Summer Night’. Like the best of short stories (and poetry), they also leave the reader full with a sense of being on the brink of discovery or revelation.

Bowen also has an extraordinarily keen sense of place; psycho-geography in her fiction is sometimes more important than the characters placed into it. As she wrote to Virginia Woolf: ‘places are so very exciting: the only proper experiences one has’, with ‘the advantages of short stories [being] that means a different place every time’. The story ‘Ivy Gripped the Steps’ dedicates its first three pages to place, describing in minute detail a house fallen into ruin. Its sentences are long and intertwined, like the ivy it describes:

One was left to guess at the size and the number of windows hidden by looking at those in the other side. But these, though in sight, had been made effectively sightless: sheets of some dark composition that looked like metal were sealed closely into their frames […] Had not reason insisted that the lost windows must, like their fellows, have been made fast, so that the suckers for all their seeking voracity could not enter, one could have convinced oneself that the ivy must be feeding on something inside the house.

These sentences are hard work, knotted, hampering and frustrating to the reader who desires a plot to roll out before them but is instead left to ponder the boarded windows of a house they may not yet care about. These opening pages not only successfully conjure a strangulated sense of place and waste, but also of what it is to read Bowen: in the words of Andrew Bennett and Nicholas Royle, from Elizabeth Bowen and the Dissolution of the Novel, the effort it requires to be ‘knit up’ by her prose. The openings also challenge the brave reader to penetrate Bowen’s ‘dark composition’, to pry open the windows, revivify the ruins and make stories with her.

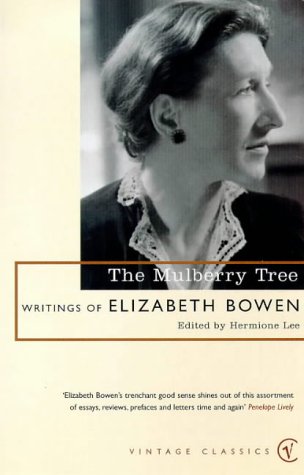

Elizabeth Bowen’s style is extraordinary, it is eccentric. One of the things Bowen admired in Katherine Mansfield was her capacity to make ‘glass-transparent’ prose using a style ‘so flexible as to be hardly a style at all’. In Mansfield’s stories ‘[t]here are’, states Bowen, in writings now collected in The Mulberry Tree, ‘no eccentricities’. For all the affinities these two writers shared, the same cannot be said of Bowen. Whether she was aware of it or not, Bowen was a decidedly queer writer, and ‘queer’ is a word that beats like a rhythm through her stories. Her style is contingent, some readers find that it gets in the way – A. G. Macdonell described it, in an article for The Observer, as ‘like a giraffe in a drawing-room’ because you ‘could not overlook its presence but you would find it hard to account for’. Yet this is also the delight of Bowen. Some of the oddest prose in Bowen’s work is not only its most striking but its most meaningful. One such moment occurs in ‘Tears, Idle Tears’, in which an older girl meets a boy in a park. Thinking about him as he retreats, she conceives of his eyes with devastating clairvoyance as ‘wounds, in the world’s surface, through which its inner, terrible unassuageable, necessary sorrow constantly bled away and as constantly welled up’. Or, in ‘The Cat Jumps’, we are given the more comedic but equally savage: ‘She would be there, densely, smotheringly there. She lay like a great cat, always, over the mouth of his life’. Elsewhere, in ‘A Love Story’, Bowen offers us this irrational yet meaningful description: ‘He switched the lights off, folded his arms, slid forward and sat in the dark deflated – completely deflated, a dying pig that has died.’

Elizabeth Bowen’s style is extraordinary, it is eccentric. One of the things Bowen admired in Katherine Mansfield was her capacity to make ‘glass-transparent’ prose using a style ‘so flexible as to be hardly a style at all’. In Mansfield’s stories ‘[t]here are’, states Bowen, in writings now collected in The Mulberry Tree, ‘no eccentricities’. For all the affinities these two writers shared, the same cannot be said of Bowen. Whether she was aware of it or not, Bowen was a decidedly queer writer, and ‘queer’ is a word that beats like a rhythm through her stories. Her style is contingent, some readers find that it gets in the way – A. G. Macdonell described it, in an article for The Observer, as ‘like a giraffe in a drawing-room’ because you ‘could not overlook its presence but you would find it hard to account for’. Yet this is also the delight of Bowen. Some of the oddest prose in Bowen’s work is not only its most striking but its most meaningful. One such moment occurs in ‘Tears, Idle Tears’, in which an older girl meets a boy in a park. Thinking about him as he retreats, she conceives of his eyes with devastating clairvoyance as ‘wounds, in the world’s surface, through which its inner, terrible unassuageable, necessary sorrow constantly bled away and as constantly welled up’. Or, in ‘The Cat Jumps’, we are given the more comedic but equally savage: ‘She would be there, densely, smotheringly there. She lay like a great cat, always, over the mouth of his life’. Elsewhere, in ‘A Love Story’, Bowen offers us this irrational yet meaningful description: ‘He switched the lights off, folded his arms, slid forward and sat in the dark deflated – completely deflated, a dying pig that has died.’

Bowen’s style was undeniable, as palpably present and contingent as life itself. Absurd, delightful, terrifying; Bowen’s stories reflect a world which turns regardless, one which is perhaps best viewed from the periphery. Her passion for the short story stemmed from its elastic ability to capture all of this. In her own words: ‘The short story, as I see it to be, allows for what is crazy about humanity: obstinacies, inordinate heroisms, “immortal longings”.’ Bowen perhaps chose to be wedded to the short story as they had so much in common. Both are crazy, obstinate, inordinately heroic.

~

Aimee Gasston is finalising her PhD at Birkbeck, University of London, where her research focuses on modernist short fiction and material culture. She won the fourth Katherine Mansfield Essay Prize and has published articles on literature and snacks, cannibalism and phenomenology. She also writes short fiction and works in the field of information rights in the public sector.

Aimee Gasston is finalising her PhD at Birkbeck, University of London, where her research focuses on modernist short fiction and material culture. She won the fourth Katherine Mansfield Essay Prize and has published articles on literature and snacks, cannibalism and phenomenology. She also writes short fiction and works in the field of information rights in the public sector.

I enjoyed this essay. It raised some interesting questions; not least, for me, what is ‘culturally improving’ about complexity? I’ll chew on that, with me butty!