photo © Dan Eckert, 2011

by David Frankel

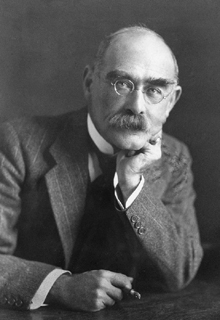

Written in 1904, ‘Mrs Bathurst’ is a story that doesn’t fit readily with a modern reader’s expectations of Rudyard Kipling. There is no imperialism or the fairy tale charm of The Jungle Book. Instead, it is filled with unease and an air of melancholy that set it apart from all but a very few of his other stories. It relates most closely to his ghost stories, many of which seem unsophisticated and predictable to a contemporary audience. They are full of plot twists and images that have, over the years since their publication, become clichés of the genre. ‘Mrs Bathurst’, however, is a genuinely unsettling story with a mysterious ending that stays with the reader.

The story begins when the narrator, an official of some kind, visits the British Fleet in South Africa and finds himself temporarily stranded in a small harbour town. Chance meetings with old acquaintances result in a group of four men, two marines and two civil servants, spending an afternoon in a deserted railway siding miles from the nearest town. This place – literally at the end of the line – forms the backdrop for a conversation about their experiences in the far-flung outposts of the British Empire.

In this, as in many of his stories of this period, Kipling goes to great lengths to show us just how isolated the men are. As the men relate different stories the location hops about more than is usual in the context of a short story, but the places they speak about are always on the edge of the sprawling empire where ‘civilisation’ is the most thinly stretched.

These far-flung locations reflect Kipling’s own experience. He was born in Mumbai in 1865 and, after a period of schooling in England, he enthusiastically returned to India at the age of sixteen. In many of his stories – a good example being ‘At the End of the Passage’ – the characters find themselves far away from ‘civilisation’, living lives ruled by imperial codes of behaviour or military regulation, in places where such ways of life are completely alien and always on the point of coming adrift.

The dialogue, with its accents, slang and naval and military references, paints a vivid and convincing image of the men. The conversation between them is adversarial and strewn with misunderstanding, building a sense of unease from the start. As the conversation continues, they begin to discuss a deserter from the Marines called Vickery, known as Click because of the noise made by his false teeth. The story that emerges from their conversation is one of Click’s obsession with a woman, the eponymous Mrs Bathurst, and his eventual undoing.

The dialogue, with its accents, slang and naval and military references, paints a vivid and convincing image of the men. The conversation between them is adversarial and strewn with misunderstanding, building a sense of unease from the start. As the conversation continues, they begin to discuss a deserter from the Marines called Vickery, known as Click because of the noise made by his false teeth. The story that emerges from their conversation is one of Click’s obsession with a woman, the eponymous Mrs Bathurst, and his eventual undoing.

The conversation is, to begin with, full of small offshoots from the main narrative. The lengthy and seemingly meandering opening is partly due to the framing narrative which requires a more elaborate scene setting. Like many of Kipling’s supernatural tales, this lengthy and almost banal opening has a flattening effect that belies the strange events that will unfold. The build-up of tension works because there is a sense of something about to happen: a secret to be revealed. By its nature, the framed narrative implies that whatever we are about to be told is a story worthy of re-telling.

In the case of ‘Mrs Bathurst’, the framed narration of the story performs another important service; it allows Kipling to get away with not revealing everything, enabling him to create a sense of mystery without leaving the reader feeling deceived. This forces the reader to consider the possibility that the narrator(s) may be untrustworthy. They are, we soon realise, recounting a story of which they have only partial knowledge. Most of Click’s story is related by Pyecroft, the only member of the group previously unknown to the central narrator, and he openly admits to his own unreliability – “I’m only giving you my résumé of it all because all I know is second ’and so to speak, or rather I should say, more than second ’and.”

Click, described by Pyecroft (presumably ironically) as ‘a superior man’, is not a promising romantic hero. Injuries have left him scarred and wearing wooden teeth. As a character he is both tough and unstable: at one point he threatens to kill Pyecroft in such a way that his friend does not doubt the threat. Despite all this, his vulnerability is evident throughout the story. He struggles to communicate his evident love for Mrs Bathurst to his friend, but we see the strength of his feeling through the unravelling of his sanity.

Although we have a clear picture of the grizzly Click, Kipling provides barely any description of Mrs Bathurst. She is introduced to us as the keeper of an Auckland boarding house and pub, frequented by the servicemen on sojourn in the port. She has a legendary status among the men for her kindness and charm but, realistically, the marines who recall their memories of her don’t have the vocabulary to convey them.

One of the party picks Pyecroft up on this, drawing the reader’s attention to the lack of concrete description, ‘I don’t see her somehow’. Yet we are left in no doubt of the impression Mrs Bathurst makes on those who meet her: Sergeant Pritchard, after confessing that he can barely remember any of the “’undreds” of women he has been intimate with, admits that he ‘…can remember every time that he ever saw Mrs B’. Pyecroft then provides us with the closest we are offered to a description of the woman: “So can I […] how she stood an’ what she was sayin’ an’ what she looked like. That’s the secret. ’Tisn’t beauty, nor good talk necessarily. It’s just It.”

The lack of physical description allows her to become a blank canvas onto which the reader projects an image, but, more than that, the characters’ inability to describe what it is about her that captivates every man that meets her gives her an unreal, mythological quality, even though she is only a landlady. We know she is desirable not because of any description that is offered, but because she is desired by the men in the story.

Having established the myth of Mrs B and her unlikely relationship with Click, the crux of the story comes when Pyecroft accompanies Click to see the new modern spectacle of a cine-reel in a travelling circus. The film being shown is called ‘Home and Friends’, showing images of England and London, including a sequence in which a train arrives and disgorges its passengers onto a busy platform – a further reminder for the characters (and readers) that they are a very long way from home. Mrs B’s legend is further established when, to the amazement of the men, she appears in the film and is immediately recognised by many of them. “She looked out, straight at us with that blindish look […] she walked on till she melted out of the picture like – like – a shadow jumpin’ over a candle.”

Having established the myth of Mrs B and her unlikely relationship with Click, the crux of the story comes when Pyecroft accompanies Click to see the new modern spectacle of a cine-reel in a travelling circus. The film being shown is called ‘Home and Friends’, showing images of England and London, including a sequence in which a train arrives and disgorges its passengers onto a busy platform – a further reminder for the characters (and readers) that they are a very long way from home. Mrs B’s legend is further established when, to the amazement of the men, she appears in the film and is immediately recognised by many of them. “She looked out, straight at us with that blindish look […] she walked on till she melted out of the picture like – like – a shadow jumpin’ over a candle.”

For Click, the film acts as a summoning of the ghostlike Mrs B, an image emphasised by her ‘blindish look’ and the way she melts out of the picture. The effect on him is immediate. He is plunged into an obsessive longing for her and begins counting the minutes until he can return for the next evening’s screening. This goes on for the next few nights, each time accompanied by Pyecroft who becomes increasingly worried and fearful of Click’s mood. Matters are brought to head when Pyecroft inadvertently asks, “I wonder what she was doing in England… Don’t it seem like she was lookin’ for somebody?” When the circus packs up and leaves town, Click is left haunted by the idea that Mrs B was looking for him and is filled with a desperate urge to find her.

In several of his stories, Kipling uses ‘modern’ technology as a trigger for the supernatural. The story of Mrs Bathurst revolves around technology that had an enormous impact on Kipling’s world, physically and, most importantly in this context, psychologically. Trains appear in every stage of the story: the framing narrative, the cine-reel, and Click’s story. Faster transport allows us to travel greater distances but, in doing so, it isolates us from those we leave behind and this is particularly poignant here. The cine-reel too is at the core of the story. The effect of the first motion pictures on their audiences is well documented. This is brought into focus when Pyecroft says, “The pictures were the real thing… alive an’ moving.” The idea of a person’s moving, ‘living’ image being captured in time is a potent one.

Mrs Bathurst is not a story of the supernatural, but if a ghost is an image of a person frozen in time, then Mrs B’s film appearance fits perfectly. In Kipling’s most famous ghost story, ‘They’, the word “ghost” is never used, despite the presence of what are clearly the ghosts of children. Both ‘They’ and ‘Mrs Bathurst’ are filled with the same sense of loss, and in both the spectre that haunts the protagonists is, in reality, an absence.

Finally, after being sent up country to oversee a military shipment, Click deserts and disappears. This is made more mysterious by the fact that his time in the navy is almost over. We conclude, as the narrator does, that he has run away to find Mrs B, driven half mad by her image in the film. At this point Hooper, one of the other men present, reveals that the charred bodies of two people were found beside a railway deep in the rainforest. They had been killed and burned to charcoal by a lightning strike and remained in position, one standing and one crouched beside the first. Click is identified as the standing figure by his tattoos and false teeth which are now in Hooper’s waistcoat pocket, a souvenir of the ghastly discovery.

The end of Mrs Bathurst is haunting and genuinely discomforting. No attempt is made to explain how Click might have come to be on a rail line deep into the interior of Africa. Nor is it ever proven that the second figure is that of Mrs Bathurst. It is certainly what the narrator and his group believe, and the reader is led to this conclusion by the structure of Kipling’s narrative. The idea is given force by the song from a passing picnic party as the men discuss the identity of the bodies:

“Underneath the bowyer, ’mid the perfume of the flower,

Sat a maiden with the one she loves the best.”

But maybe we and the narrators are both led to the same unfounded conclusion by the trail of coincidental clues.

We, like the men in the story, want the tale to resolve itself and we search for the resolution in the story’s many clues. In this case, our hope for an ‘easy conclusion’ is confounded by the obvious question of how Mrs Bathurst came to be on a train track in Africa. This doubt is given some weight by the somewhat enigmatic quotation from a fictional play – Lyden’s ‘Irenius’ – that prefaces the story. The ‘excerpt’ appears to have little to do with the story, except for the line, ‘She damned him to death and knew not that she did it’, which implies that Mrs B never knew Click’s fate.

The mysterious ending might, in some ways, leave the reader unfulfilled and it has been suggested that Kipling, a ruthless cutter of material, made the story impossible to understand by over-cutting. However, we wouldn’t bother trying to interpret the story if it failed to engage us emotionally. Ultimately, we are hooked into the story because it shows guilt, obsessive love, desertion and tragedy in the lives of very ordinary people at the mercy of accident and coincidence. As Mr Pyecroft points out, “Even a sailor as an ’eart to break”.

Maybe the point of Kipling’s story is that neither the narrators nor we the readers can ever really know the content of other people’s experience – the characters in the story see only flashes of each other’s lives and piece together the rest. Perhaps Kipling was trying to suggest that we will only ever see each other from a distance, unable to get close enough to understand each other, as Pyecroft saw the figures in the cine-reel: “When anyone came down too far towards us that was watchin’, they walked right out of the picture, so to speak.”

~

David Frankel recently completed an MA in Creative Writing at the University of Chichester and was awarded the Kate Betts Memorial Prize. His stories have been published in anthologies and magazines including The London Magazine and Lightship Anthology. He has been short and longlisted for a number of prizes, including The Willesden Herald Short Story Prize, the Fish Memoir Prize and the Hilary Mantel Short Story Prize. When he isn’t writing, he works as an artist.

David Frankel recently completed an MA in Creative Writing at the University of Chichester and was awarded the Kate Betts Memorial Prize. His stories have been published in anthologies and magazines including The London Magazine and Lightship Anthology. He has been short and longlisted for a number of prizes, including The Willesden Herald Short Story Prize, the Fish Memoir Prize and the Hilary Mantel Short Story Prize. When he isn’t writing, he works as an artist.