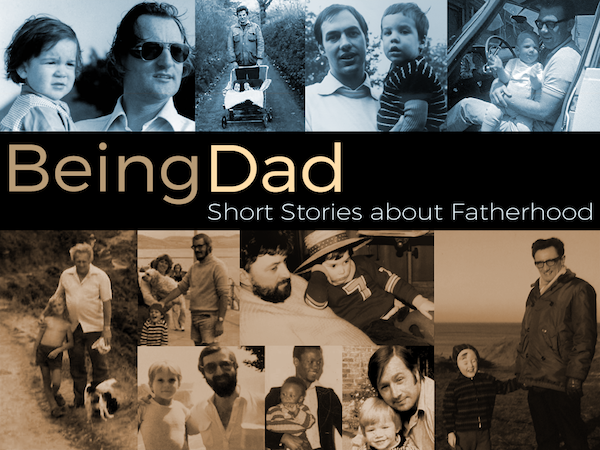

photo © Being Dad

The Being Dad crowdfunding campaign was a success and the anthology has been funded. Just days before it closed, we caught up with contributing author Dan Powell, to find out a little more about this unusual short story project and Powell’s short story writing…

~

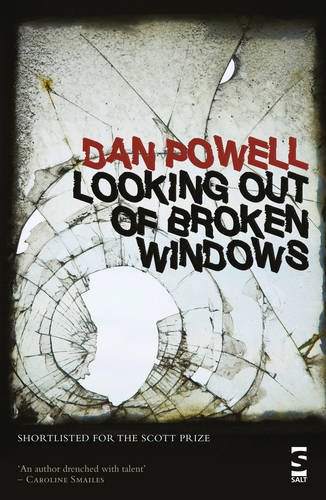

Dan Powell is a prize-winning author of short fiction whose stories have appeared in the pages of Carve, New Short Stories, Unthology, The Lonely Crowd and The Best British Short Stories. His debut collection of short fiction, Looking Out Of Broken Windows, was shortlisted for the Scott Prize, longlisted for the Edge Hill Prize, and is published by Salt. He teaches part-time and is a First Story writer-in-residence. He has stories forthcoming in both Being Dad: Short Stories about Fatherhood (Tangent Books, March 2016) and The End: Fifteen Endings to Fifteen Paintings (Unthank, April 2016). He procrastinates at danpowellfiction.com and on Twitter as @danpowfiction.

Dan Powell is a prize-winning author of short fiction whose stories have appeared in the pages of Carve, New Short Stories, Unthology, The Lonely Crowd and The Best British Short Stories. His debut collection of short fiction, Looking Out Of Broken Windows, was shortlisted for the Scott Prize, longlisted for the Edge Hill Prize, and is published by Salt. He teaches part-time and is a First Story writer-in-residence. He has stories forthcoming in both Being Dad: Short Stories about Fatherhood (Tangent Books, March 2016) and The End: Fifteen Endings to Fifteen Paintings (Unthank, April 2016). He procrastinates at danpowellfiction.com and on Twitter as @danpowfiction.

~

Being Dad is an anthology of brand new fiction about fatherhood, put together by short story writer and former Litro editor Dan Coxon. After meeting many writers within the short story community who were fathers, he realised that few had written about their experiences. Coxon chose to pursue crowdfunding for this project because publishers tend to shy away from short story anthologies. The Kickstarter campaign was to raise funding to cover costs for the initial print run, and to pay the writers for their work – Toby Litt, Dan Rhodes, Nikesh Shukla, Courttia Newland, Nicholas Royle, and many others are involved.

*

Vicki Heath talks with Dan Powell:

*

Vicki Heath: Let’s start with a question about writing, for a change: how do you write? Laptop? Pencil? In an attic? At the kitchen table while your kids do their homework?

Dan Powell: I am fortunate enough to have a study, small though it is, to work in. I have a standing desk with my laptop hooked up to an external display where I do most of my work. The standing desk is one of the Varidesk ones that you can set for standing or sitting, so I alternate during a writing session, every twenty-five minutes or so. I do most of my work straight to computer but will write in a notebook (always with a Space Pen) or on my typewriter (I have an old 1950s Bluebird set up next to my standing desk). I often first draft on the typewriter as it forces you to really think about each word and sentence in a way that the easy delete of a word processor doesn’t. As for when I write, I write whenever I can. I am lucky enough to have a few days each week to focus on my writing, but I also often wake early to get an hour or two in before the kids are up, particularly at weekends and during school holidays. I’d love an attic room to write in though.

VH: I’m really looking forward to the Being Dad anthology; from the sample of stories I’ve seen, it’s going to be an impressive read. What appealed to you about the project and its crowdfunding campaign?

DP: I’ve been a stay at home dad for over ten years. Even now, while I am teaching part time, I am the main-carer for the kids during the week, so fatherhood is at the core of what I do on a day to day basis. It is a theme that I touch on in a lot of my work, but as Dan Coxon, editor of Being Dad, has pointed out before, there’s not really a vast amount being published on the subject. When he approached me about contributing to the project, it struck me as exactly the sort of thing I would love to read and, even better, to be part of. I haven’t read any of the other stories in the collection yet, and I can’t wait to get my hands on a copy and dig in to the other writers’ perspectives on the subject.

VH: Your story for Being Dad, ‘A Father’s Arms’, moves carefully between the vulnerabilities of being both a father and a son. When you were asked to write a story for the collection, did you immediately think this was the way to go?

DP: Because the subject of fatherhood is something so close to me, I struggled for a while about how exactly to approach writing something for the collection. I attempted a couple of more fictional stories but it felt a little like faking it. I may end up going back to those ideas and trying them again, but for this project I wanted to write something a little more grounded in the realities of being a father. My own father died about two years before my eldest child was born. To me the two events, the passing of my father and my own becoming a father, are linked, and I have felt his absence keenly with the arrival of all my children. I knew before I began writing that the narrator’s father was going to be a presence in the story, that the story would be about being a father and a son, as, after all, all fathers are sons.

DP: Because the subject of fatherhood is something so close to me, I struggled for a while about how exactly to approach writing something for the collection. I attempted a couple of more fictional stories but it felt a little like faking it. I may end up going back to those ideas and trying them again, but for this project I wanted to write something a little more grounded in the realities of being a father. My own father died about two years before my eldest child was born. To me the two events, the passing of my father and my own becoming a father, are linked, and I have felt his absence keenly with the arrival of all my children. I knew before I began writing that the narrator’s father was going to be a presence in the story, that the story would be about being a father and a son, as, after all, all fathers are sons.

VH: I understand that ‘A Father’s Arms’ is quite autobiographical; what was the writing process like?

DP: Many of the events in the story are taken directly from my life, though they have been fictionalised, of course. The process of writing this story was different from any other I’ve written, though. I started by writing short snippets of scenes, just in an attempt to get a glimpse of what it was I might want to say about fatherhood. Once I had five or six of these scenes, I looked closely at each one to see how they overlapped, what linked each of the different events. I only knew I really had a story when I hit on the non-chronological structure, which allowed me to move the scenes around for, I hope, best effect. Most often my writing process is quite linear, writing from beginning to end of a piece, but this was more sporadic, like flashes of memory. Hopefully in the reading it reflects the way one memory can spark another and how a memory can feel suddenly very present.

VH: Where is the line drawn between you and your character? And, for that matter, between your children and your character’s children?

DP: The names have been changed, but most things that happen in the story happened in life. That said, I have played around with structure and detail to make a more cohesive narrative. Even where I have changed things, and I haven’t changed all that much, there is an emotional truth that I took directly from that moment and kept close watch on. When my wife read the story she was a little surprised by how close a reflection of our lives it is, but she also said it would be a great thing for our kids to read when they’re old enough to appreciate it.

VH: It’s quite a choking story, as the narrator longs for his deceased father’s presence whilst struggling through various hospital visits with his own children. In ‘Half-mown Lawn’, your story collected in The Best British Short Stories 2012, heartbreak for one who has died is equally prevalent – if not more so – is it difficult to write these very moving scenes?

DP: It is and it isn’t. The more moving scenes of both those stories are amongst the quickest and easiest I have produced in terms of the simple mechanics of putting words on paper. These kinds of scenes tend to unfold suddenly for me, as if in real time, and they take little longer to write in first draft than they take to read. The moment unfurls quite naturally as I draft. That’s not to say I don’t struggle with other kinds of scenes. I do. Every day. But these scenes have an energy and a force that seems to impel them towards their climax. It’s in the edit that these scenes become difficult. Trying to shape the raw emotion on the page so that every sentence is building just enough, that is where these scenes become difficult. I rework and rework them because I want to be sure they aren’t cheap, that they aren’t just taking an easy tug on the reader’s heart strings. I know I’m on to something when I’m reading the twelfth edit of a scene and it still puts a lump in my throat, still brings a tear to my eye.

VH: The narrator’s father in ‘A Father’s Arms’ is described as being ‘a new man before all that new man crap in the Eighties’. There’s also a condescending nurse in the story, who belittles the narrator, largely because he’s the one taking the baby for her jabs, not the mother. Are perceived gender roles in parenting an important theme for you to explore in your writing?

DP: I think my awareness of perceived gender roles and the difficulties of challenging them came at a young age. My dad was really hands on. He worked nights when I was little and took care of me and my brother and sister during the day, while Mum was working. He must have been shattered but I only remember him being fun to kick around with. He helped with the household chores and always preferred being home to being anywhere else. He used to get quite annoyed about the whole new man thing when they became a popular image. He really was a new man before new men existed.

It’s weird to think that, thirty years later, this kind of thing can still be a big deal for some people. My wife is the main wage earner and provides for our family. She is a brilliant mother, yet many times she has faced disapproval regarding her undertaking this traditionally male role. When my youngest lad was in hospital for an op at the age of one, I stayed with him for the three days he was there, as I was the one at home with him at the time. Many of the staff in the ward found this remarkable and, while they were friendly and helpful with me, there was a real coolness when my wife came in for visits. There was a definite judgement going on, some of the staff were clearly looking at her and wondering what kind of woman doesn’t stay home to care for her child.

As for me, I have faced the kind of belittling that my narrator has to deal with many, many times. Most people are genuinely open to the idea of parents switching traditional roles but that only serves to make those less enlightened individuals more annoying when you do come across them. And don’t get me started on the popular advertising stereotype of the clueless dad.

VH: Did becoming a dad change the themes and preoccupations of your stories?

DP: Becoming a dad has influenced my writing in many ways. Most obviously in those stories that feature parent-child relationships at the fore, but it also had a more practical impact. Before I had young children sucking up huge swathes of my waking life, I was a world class procrastinator. I put off writing, knowing that I could always find time tomorrow. As a result, I got very little done. As soon as my eldest came along it became apparent that there wouldn’t always be time tomorrow, so I began squeezing every bit of writing time out of today. Also, my kids inspire me every day. I’ve written loads of stories that I would never have been able to write had they not come into my life. In that regard, ’A Father’s Arms’ is just the latest example. They help me see the world and my place in it with fresh eyes.

VH: You are, of course, a familiar name here on Thresholds – incredibly, three times shortlisted and twice runner-up in our annual Feature Writing Competition – is the study of writing crucial to you as a story writer?

DP: Absolutely. A writer needs to read, everything and anything. If you want to write short stories you need to read them. I love digging into great stories, initially for the sheer reading pleasure, but I go back to the ones that stick in my head, to take them apart and see how they tick. There are so many great short stories, I feel like I’ve only scratched the surface of what is out there and always enjoy discovering new work and new writers. So, yes, the study of good writing is crucial; it helps me see me how much further I have to go with my work.

VH: You’ve written about Chekhov, Norwegian author Kjell Askildsen, graphic story writer Yoshihiro Tatsumi, and Swedish author Stig Dagerman for Thresholds – but who is your ultimate writing inspiration?

DP: Chekhov has perhaps influenced me more than any other writer, at least so far as short fiction goes. His early comic and surreal tales showed me how to incorporate humour and oddness into more realistic stories without it seeming jarring, and the way he melds the comic and the tragic into a cohesive whole is something I continue to attempt from time to time.

DP: Chekhov has perhaps influenced me more than any other writer, at least so far as short fiction goes. His early comic and surreal tales showed me how to incorporate humour and oddness into more realistic stories without it seeming jarring, and the way he melds the comic and the tragic into a cohesive whole is something I continue to attempt from time to time.

That said though, I take inspiration and guidance from a whole host of writers. I think that’s how you stumble toward your own style, your own voice. You read widely and take little bits from each of your influences until, finally, hopefully, it all filters through you into something new.

Edgar Keret, Aimee Bender and Adam Marek have shown me how to explore the weird within otherwise realistic settings. Amy Hempel, Raymond Carver and Kjell Askildsen have shown me how less can break the reader’s heart more. Right now, I am reading a lot of William Gay and I’m in awe of the perfect shapes of his stories. I’m trying to work out how he writes such gut-wrenching endings. His writing, sentence by sentence, is some of the best I’ve ever read, so I am savouring his collection and planning to dig back into the stories there to catch a glimpse behind the curtain.

VH: Your debut short story collection, Looking Out of Broken Windows, was published by Salt. Was it easy to find a publisher?

DP: Being published by Salt has been a real surprise and a pleasure. A surprise because, though the collection was shortlisted for the 2013 Scott Prize, Kirsty Logan’s collection won the prize and the publishing deal. A few days after the prize announcement, Jen at Salt contacted me and asked if I would like to publish with them anyway. It still feels a little unreal that my debut collection of stories is out there and being read.

VH: Since the collection, you’ve written a novel – can you sum it up in one sentence?

DP: The Mechanics of Impact tells the story of a career teacher who one day, seemingly out of the blue, assaults a student, and explores both the causes of the devastating event and its consequences.

VH: Sounds good! And is there another short story collection in the pipeline?

DP: I am currently putting together a collection of stories under the title All Men In Disguise. It’s themed around ideas of masculinity in the 21st Century. I have about seven stories ready to go, but want a good few more before I start selecting the best combination of stories for this one. It’s shaping up nicely though.

VH: Dan, thanks so much for this insight into the Being Dad project and your writing. We look forward to hearing more when the book comes out next year.

~

Find Being Dad at Kickstarter, on Facebook and on Twitter @BeingDadStories.

With thanks to Dan Coxon.