photo © Anna, 2011

by Alan McMonagle

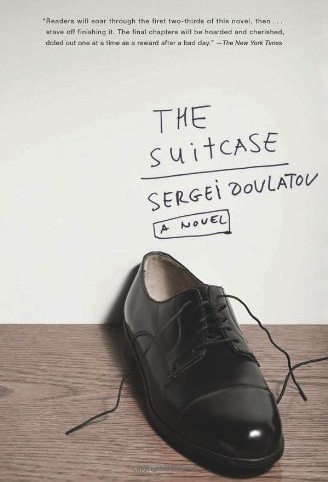

One day in the early nineteen eighties the Russian émigré-writer Sergei Dovlatov opened the door of a seldom-used closet in his Forest Hills apartment in New York City. From inside the musty space he withdrew a long-forgotten plywood suitcase. The lock was broken, a piece of clothes line held it closed. It was the suitcase he had taken with him upon fleeing the USSR several years previously. He opened the suitcase and beheld what amounted to eight different items: some Finnish crêpe socks, a pair of half-boots, a decent double-breasted suit, an officer’s belt and a poplin shirt, a jacket belonging to one Fernand Léger, a winter hat and a set of driving gloves.

These items, by turn, become the players in Dovlatov’s collection of stories The Suitcase, as the author’s alter-ego proceeds to inventory the circumstances under which he came into possession of them.

It is very much these circumstances that take centre stage and give these stories their humorous, fraught and compelling energy. The stories are set in the 1960s, in that great Russian literature city of Leningrad. It is a Russia of socialist ideology: the thought police are watching your every move; big brother hovers. However, rather than merely railing against the oppressive system, Dovlatov upends expectations by embracing the terms of his existence as further demonstration of the human condition and of the absurdity inside us all. His approach is original and delightful, and chastises the circumstances of his life without raising a word in anger or positioning his alter-ego narrator as an embittered casualty.

The stories, then, are perfectly suited to their first-person narrative viewpoints – favouring characterisation and situations over plot, the lend-me-your-ears tone gives the impression that these mordantly comic tales are for you and no one else. The atmosphere of the stories is fraught, chaotic, yet compellingly human. Take the confessional tone of ‘The Nomenklatura Half-boots’. Two master stonemasons, who take a nice sideline in vodka swilling and ridicule, take on the narrator as their apprentice. Securing an important commission (to be ready on the occasion of an auspicious visit), they set about creating a masterpiece while simultaneously attempting to maintain their vodka intake. They are broke and need the money. They cannot work without drinking. They cannot drink without a tricksy journey from their underground workshop to the nearest bottle shop. Theirs is a road ever-spiralling, and every twist and turn is a treat, shot through with subtle irony and hilarious observation.

Once I visited the studio of a famous sculptor. His unfinished works loomed in the corners. I quickly recognised Yuri Gagarin, Mayakovsky, Fidel Castro. I looked closer and froze – they were all naked. I mean, absolutely naked. With conscientiously modelled buttocks, sexual organs and muscles. I felt a chill of fear.

“Nothing unusual,” the sculptor explained. “We’re realists. First we do the anatomy, then the clothes…”

The story set-ups are brilliant. In ‘The Finnish Crêpe Socks’, the narrator joins an increasingly incompetent gang of black marketers. ‘An Officer’s Belt’ hilariously regales the efforts of two prison guards, bumbling and inept, asked to escort a prisoner pretending to be crazy. The oh-so-autobiographical-sounding ‘A Poplin Shirt’ recounts how, as a little known writer, the narrator meets his wife for the first time, and how he tries to impress her by taking her to a literary salon frequented by the most famous writers of the time. Eventually, one of these writers notices the narrator and acknowledges a piece of his writing before offering a damning verdict: “I read your humour piece in Aurora. It’s crap.” As with other stories, it is such moments of light-touch pathos that elevate these self-deprecating situations.

The story set-ups are brilliant. In ‘The Finnish Crêpe Socks’, the narrator joins an increasingly incompetent gang of black marketers. ‘An Officer’s Belt’ hilariously regales the efforts of two prison guards, bumbling and inept, asked to escort a prisoner pretending to be crazy. The oh-so-autobiographical-sounding ‘A Poplin Shirt’ recounts how, as a little known writer, the narrator meets his wife for the first time, and how he tries to impress her by taking her to a literary salon frequented by the most famous writers of the time. Eventually, one of these writers notices the narrator and acknowledges a piece of his writing before offering a damning verdict: “I read your humour piece in Aurora. It’s crap.” As with other stories, it is such moments of light-touch pathos that elevate these self-deprecating situations.

Dovlatov’s alter-ego fares out little better in ‘A Decent Double-Breasted Suit’. Here, under the guise of his journalist credentials, he attains a dubious role accompanying a suspected spy to the theatre. He has nothing suitable to wear and the KGB officer on his case insists that the newspaper our narrator works at coughs up the price of a new suit. By the end of the story, our narrator has secured a high-fashion suit and a few more ‘gigs’. However, we are never in doubt that this little piece of good fortune has come at a larger, soon-to-reveal-itself cost. And so it goes.

In ‘The Winter Hat’, to his eternal dismay, not one, but three of the narrator’s female friends fall in love with his brother. In ‘The Driving Gloves’ the unsuspecting narrator is given the role of Tsar Peter the Great in a short film a newspaper colleague wants to make, satirising the paralysis-inducing political system. And, for all the wit and playful banter on display, ‘Fernand Léger’s Jacket’ makes us slowly aware of the fragile sensibility sustaining this prince-and-the-pauper fable.

All my conscious life I was drawn instinctively to damaged people — the poor, or hooligans, or budding poets. I tried making respectable friends a thousand times, always in vain. It was only in the company of savages, schizophrenics and scoundrels that I felt confident.

And yet, for all the disappointments and missteps and frustrated ambitions and plans gone awry, for all the broken promises and thwarted dreams, Dovlatov never allows his narrators to position themselves as victims. Nor are his adversaries ever quite the villains of the piece. If there is one essential truth trying to break through the chaotic world of his writing, it is that the terms of our existence are often unfair, harsh and even cruel – but, hey, let’s get on with it.

There is so much awareness and knowing and instinct in any of Dovlatov’s stories. He avoids obvious epiphany and easy exits, preferring instead to conjure miracles from the seemingly banal. He dares his alter-egos into unsafe territory and is hilariously scathing when things don’t work out:

No wonder my wife says, “You’re interested in everything except conjugal obligations.” By ‘conjugal obligations’ my wife means sobriety, first and foremost.

~ ‘The Driving Gloves’

His women are tough, demonstrative and unafraid to act. Meanwhile, his men drink, flirt, bumble from moment to moment, dice with authority and, by extension, a regime that can snuff them out like chaff in a breeze. Life in a Dovlatov story is moment-by-moment chaos, fraught with casual cruelties, self-mockery and spirited defiance. And then, when you least expect it, tenderness seeps through, with a tantalising hint at lurking vulnerability; a yearning for another, brighter world.

I saw the sky, enormous, pale and mysterious. So far away from my problems and disappointments. So pure. I gazed at it in admiration until a shoe kicked me in the eye. And everything went dark…

~ ‘The Winter Hat’

As well as having a sense of chaos in his stories, Dovlatov is also mordantly funny. He is a master of that oh-so-tricksy thing, the non sequitur, and his feather-weighted pathos can break your heart without your knowing what is happening to you. Woody Allen said that comedy equals tragedy plus time and I have a feeling he ‘borrowed’ this line from one of the great Russians. But I think comedy and tragedy run together, co-exist; the one throws light on the other. In Dovlatov’s case, his bleak humour is always a nod-and-wink to the illogicality of human behaviour and to the walls we continually build around ourselves. And despite the antic humour there is a film of regret – scarcely visible, but there – hovering over these stories, along with layers of earnestness that more celebrated writers have seldom achieved.

I used to drink a fair amount; consequently, I hung out in some strange places. That made many people think I was sociable, whereas all you had to do was sober me up to see my sociability vanish.

~ ‘A Poplin Shirt’

These disparate elements (humour, chaos, regret, earnestness) perfectly lend themselves to Dovlatov’s hinterland of vodka bars, black markets and dodgy pawnshops; corrupt officials and turncoat friends; petty thieves, inept swindlers and deals gone sour. The course of each story has a mind of its own: it can stray off, jerk suddenly in surprising and unexpected directions, and then, just like that, we’re back on familiar ground again, delighted to have been smuggled into the sideshow.

These disparate elements (humour, chaos, regret, earnestness) perfectly lend themselves to Dovlatov’s hinterland of vodka bars, black markets and dodgy pawnshops; corrupt officials and turncoat friends; petty thieves, inept swindlers and deals gone sour. The course of each story has a mind of its own: it can stray off, jerk suddenly in surprising and unexpected directions, and then, just like that, we’re back on familiar ground again, delighted to have been smuggled into the sideshow.

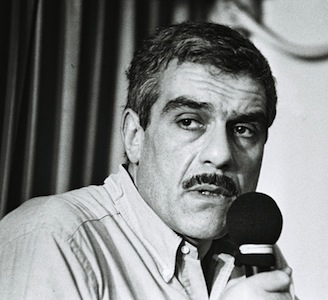

For years Dovlatov’s writing was banned in his home country. He often had to resort to smuggling his manuscripts out of the country, with authors prepared to run the risks and punitive consequences. Then, beginning in 1976, he began to find an audience among Russians in the West, after which a period of intense harassment by Soviet authorities ensued. In 1978, he emigrated to the United States. Dovlatov’s stories started to appear in English in the 1980s and he was championed by the New Yorker, which published nine of his stories between 1981 and 1989. He finally settled in Forest Hills, New York, where he died in 1990 at the too-soon age of forty-eight, leaving a legacy of twelve published books. The wonderful American commentator in all things literary, Francine Prose, said, ‘One wishes that he’d lived longer, been published sooner, given us more’.

Above all, what endears me most to Dovlatov’s stories is his remarkable ability to be simultaneously engaged in and removed from the world:

‘People floated past like fish in an aquarium.’

~ ‘The Finnish Crêpe Socks’

I think there is something noble, too, in the conception of this collection, something that bears witness to a crazy time in the lives of a censored citizenry; something pure and true, a magic that renders The Suitcase a collection that is more than the sum of its parts, and a fitting testimony to a life lived under duress. Every time I read these stories, I feel a kinship with them and their preoccupations. In his afterword, Dovlatov wrote: ‘There’s a reason every book, even one that isn’t very serious, is shaped like a suitcase.’ And, to me, this collection is a suitcase worth unpacking time and time again.

~

Galway-based Alan McMonagle has published two collections of short stories, Liar Liar (Wordsonthestreet, 2009) and Psychotic Episodes (Arlen House, 2013). Last year, his radio play, Oscar Night, was produced and broadcast as part of Irish radio’s Drama on One season. He has just completed his first novel.

Galway-based Alan McMonagle has published two collections of short stories, Liar Liar (Wordsonthestreet, 2009) and Psychotic Episodes (Arlen House, 2013). Last year, his radio play, Oscar Night, was produced and broadcast as part of Irish radio’s Drama on One season. He has just completed his first novel.