photo © Renaud Camus, 2012

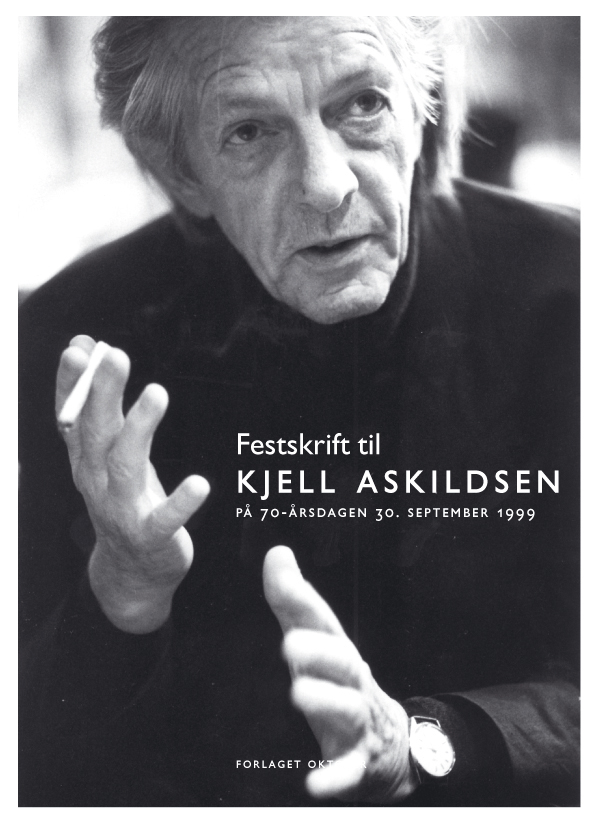

In his essay, a runner-up in the 2015 THRESHOLDS International Short Fiction Feature Writing Competition, Dan Powell considers the themes of Norwegian author Kjell Askildsen’s short stories.

Comments from the judging panel:

‘A compelling examination of the Norwegian writer Kjell Askildsen and the recurrent appearance in his work of emotionally truncated middle-aged male protagonists’; ‘a clear and engaging discussion of Askildsen’s writing style and the content of his stories’; ‘a sensitive analysis of a collection of complex stories ’.

*

Dan Powell is a prize-winning author of short fiction whose stories have appeared in the pages of Carve, New Short Stories, Unthology and The Best British Short Stories. His debut collection of short fiction, Looking Out Of Broken Windows, was shortlisted for the Scott Prize, longlisted for the Edge Hill Prize, and is published by Salt. He teaches part-time and is a First Story writer-in-residence. He procrastinates at danpowellfiction.com and on Twitter as @danpowfiction.

Dan Powell is a prize-winning author of short fiction whose stories have appeared in the pages of Carve, New Short Stories, Unthology and The Best British Short Stories. His debut collection of short fiction, Looking Out Of Broken Windows, was shortlisted for the Scott Prize, longlisted for the Edge Hill Prize, and is published by Salt. He teaches part-time and is a First Story writer-in-residence. He procrastinates at danpowellfiction.com and on Twitter as @danpowfiction.

*

Nothing is the way it used to be, yet everything is like before, or Kjell Askildsen’s Veranda Variations

by Dan Powell

If there were only one truth,

you couldn’t paint a hundred canvases on the same theme.

~ Pablo Picasso

Variation, a technique most widely employed in the fields of music and visual art, sees the artist repeat material in an altered form, creating new works that circle key themes, ideas and motifs. Rather than simply covering the same ground over and over, variation exposes untrodden paths to the truths hidden within a theme. While most writers revisit key themes and tropes in their work, it is rare to see a writer embrace variation to the extent that a fine artist or classical composer might. Norwegian author Kjell Askildsen is one such rare author who places variation at the compelling centre of his work, using the technique to delve deeply into the dark hearts of his many middle-aged male protagonists.

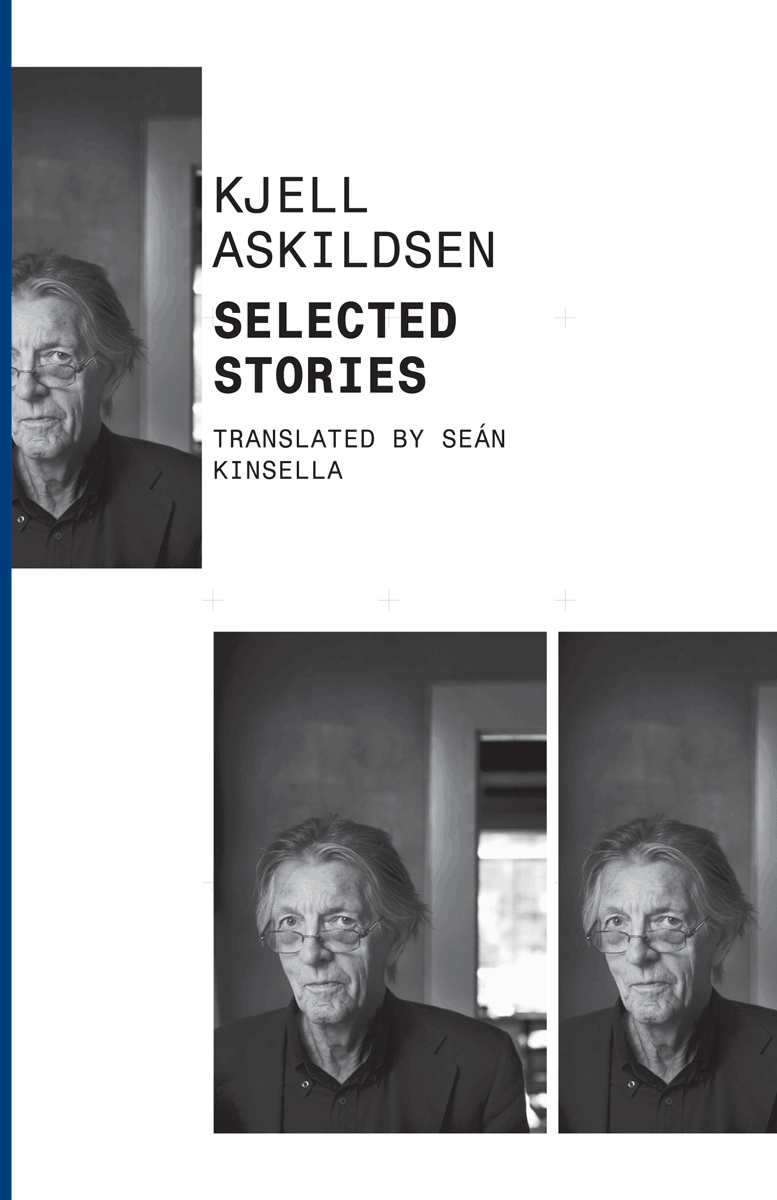

Kjell Askildsen’s Selected Stories, beautifully translated by Sean Kinsella, contains fictions from four collections published between 1982 and 1996. Fittingly, these stories are enfolded within a minimalist white cover, bearing clean, simple typography and three versions of a black and white author headshot, each variation cropped differently, subtly altering the focus of the image. This carefully considered yet simple cover design prepares the reader for the stories within.

The map of Askildsen’s fictional world is adorned with warnings: here be minimalism, repetition, variation and precise, stark prose. His stories, like his sentences, allow no clutter. Most of the fictions collected here span no more than eight or nine pages. Description is terse, practical, and verges on the perfunctory. Dialogue is strained, repressed. Any insight into a character’s motivations comes almost purely from the observation of surface action alone. Rarely does Asklidsen allow the reader access to his male narrator’s thoughts and feelings, and when he does, only the tip of the emotional iceberg is revealed. The bulk remains hidden, lurking beneath the surface, ready to sink everyone and everything it touches, the stories’ protagonists most of all.

Throughout this collection, Askildsen does not divert from his handful of central themes: the emotional inadequacy of middle-aged men; male sexuality; the anxieties of intimacy; repressed desires and the damage they inflict; the crushing suffocation of middle-age; the necessity, in long-term relationships, for lies and things best left unspoken. Instead, he circles them obsessively, each variation on his themes a new attempt to illuminate further the frustration and despair roiling inside his central character trope – the middle-class, middle-aged, suburban, white male.

Each story follows a middle-aged male protagonist as he negotiates the hazardous terrain of an unhappy marriage, or strained family relationships, and all find themselves in the grip of sudden, overwhelming despair:

I was seized by an inexplicable feeling of anxiety

~ from ‘A Great Deserted Landscape’

He felt a sudden sense of desertion, of confinement almost

~ from ‘The Unseen’

I became gripped by a feeling of anxious desertion

~ from ‘The Dogs of Thessaloniki’

Emotions bleed in and out of stories written over the course of more than a decade. Askildsen’s tendency to revisit situations – a number of the stories feature men obsessing over their sisters – and even to reuse character names while exploring these similar situations, heightens this effect. It makes each successive story unique, and yet part of some larger mesh-and-merge of plot and setting, character, relationship,  emotion and action. In the absence of other collections of his work in English translation, it is difficult to ascertain just how pervasive this focus is throughout the whole of Askildsen’s oeuvre, but, judging by the sheer proliferation of similarities in theme, subject and character in this sample of stories, it is reasonable to suppose his focus on such themes is typical of his work.

emotion and action. In the absence of other collections of his work in English translation, it is difficult to ascertain just how pervasive this focus is throughout the whole of Askildsen’s oeuvre, but, judging by the sheer proliferation of similarities in theme, subject and character in this sample of stories, it is reasonable to suppose his focus on such themes is typical of his work.

The narratives, in addition to their cognate themes, also play out against a backdrop of cognate settings. The reader is repeatedly taken into train station bars, marital bedrooms, and, most often, the verandas of quiet, suburban homes. But, at the edges of the ordered homes and landscaped gardens these men have worked to build around themselves, shadowy woods and undergrowth lurk, providing a not completely unsubtle metaphor for the dark emotional state pervading Asklidsen’s narrators. Unable to truly act within the confines of their lives, these men lie in order to effect fleeting escapes to local bars, or hide in the bushes, behind curtains, behind sunglasses, even, so they can observe the women in their life undetected. Askildsen repeatedly subverts the idea of the veranda, and by extension the home, as a relaxing, intimate space. Instead, he depicts an emotional minefield that his protagonists – one after another, after another – must remove themselves from, rather than risk the explosions that result from the slightest wrong word or mis-step. Ironic then, that these small escapes are often met with insult and even injury, a trope revealed in the opening story, ‘Martin Hansen’s Outing’, which ends with the title character being violently mugged in a train station toilet and rushed to Accident and Emergency.

Even when physically successful, these escapes fail to satisfy, and Askildsen’s men resort to fantasy to slip the emotional shackles of their failed relationships. The most harmless imagine simply leaving their partner, while others play voyeur or slip away to bedrooms in order to masturbate over a female acquaintance or relative. The narrator of ‘The Dogs of Thessaloniki’, in a sudden, unguarded thought about his wife, reveals his true, most deeply hidden desire, when he thinks, ‘if only she were dead’.

Askildsen is unafraid to examine the darkness of the hearts that beat behind the shirts and pullovers of his middle-aged narrators. Multiple protagonists fantasise about their sisters-in-law or sisters, one confronts the reader with his desire for the teenage daughter of a friend, and another reveals a salacious interest in a rape scene in a novel he is reading.

Yet Askildsen does not present these scenes to titillate. His spare, subdued prose underlines the sad, grubby nature of such fantasies and highlights the desperate and despairing emotional state of the men compelled by them. Each time a protagonist manages to temporarily free himself from the constraints of his emotionally stagnant relationships, his lusts, desires and obsessive compulsions assert control and entrap him anew. Askildsen seems to suggest that their damaged state has less to do with the broken nature of their intimate relationships and more to do with something inherently broken at the core of middle-aged men.

Just as they are unable to truly deal with their emotional crises, Askildsen’s narrators, apathetic and pathetic to a man, prove equally unable to deal with more tangible problems. In ‘The Dogs of Thesaloniki’, the narrator’s unwillingness to face up to his own lack of feeling towards his wife, is seen in his ineffectual attempt to clean a puddle of vomit deposited by some unseen passer-by outside the front gate of his house. He sprays the puddle of sick with a hose, but succeeds only in moving the mess four or five meters away from the gate. His relief at getting ‘a bit of distance from the filthy mess’ speaks volumes about the physical and emotional distance he keeps from his wife throughout the story. The narrator in ‘Where the Dog Lies Buried’ can barely bring himself to approach the partially decayed corpse of a dog that he discovers under a basement flap of his house. At first, he only manages to cover it and drag it to  the end of the garden. When, finally, he buries the corpse, its decomposition contaminates the soil of a nearby vegetable patch, just as arguments with his wife, fuelled by the situation with the dog, further curdle their already soured relationship.

the end of the garden. When, finally, he buries the corpse, its decomposition contaminates the soil of a nearby vegetable patch, just as arguments with his wife, fuelled by the situation with the dog, further curdle their already soured relationship.

Communication in the stories is almost non-existent. These emotionally repressed men rarely if ever say what they feel, or even what they mean. Their speech is terse and laced with frustration and irony, and Askildsen uses this sparse dialogue to highlight his characters’ unspoken desires. It is rare to find an unattributed piece of dialogue throughout these pages. The terse, rattling nature of what the characters say, so often short bursts of two, three, or perhaps a handful of words that fire back and forth, and the constant barrage of he-said-she-said-he-said-she-said, emphasises the banality of what the characters are saying, while simultaneously highlighting the fast moving current of subtext.

Asklidsen further heightens this effect by avoiding the use of inverted commas when punctuating speech. This stylistic choice emphasises the suffocation his characters feel. Just as the lives of his protagonists are compressed and constrained by the banal awkwardness of their situations, their words and actions are crammed together into blocks of text that almost overwhelm the reader with their density. The longer exchanges between these inhibited and frustrated characters, almost – but not quite (Askildsen’s control of his form is too great) – lose the reader in the crushing emotional claustrophobia with which his characters struggle.

If all this sounds unremittingly bleak, Askildsen’s endings provide little in the way of consolation, respite or resolution, but that is not to say they fail to satisfy. At the ends of his stories, as with all aspects of his fiction, Askildsen is concerned more with variation than innovation. His male protagonists remain trapped, their failures to effect change exposed in final, terse exchanges of dialogue. The first story, ‘Martin Hansen’s Outing’, once again sets the tone, closing with: ‘This doesn’t change anything, she said. No, I thought. Does it? she said. No, I said.’

Similarly, ‘The Unseen’ ends as night falls:

He looked at her, her features were almost erased. She said: It’s getting a bit chilly. I think I’ll go inside. Are you going to sit here for a while? He nodded. A little longer, he said.

Each story in the collection ends on a variation of this trope, with Askildsen saving his darkest take on the reassertion of the status quo for the collection’s closing story, ‘Everything Like Before’. Carl, the most sympathetic of Askildsen’s protagonists and a man no longer able to physically satisfy his wife Nina, plucks up the courage to leave her after she forces him to watch while she flirts with and kisses another man. Carl almost escapes but, inevitably, is sucked back into their damaged relationship when Nina seduces him. Their situation is first visibly reasserted – she literally wraps Carl around her little finger – then verbally reinforced:

Just before he came, she issued an inarticulate cry, and a prolonged trembling passed through her body. He didn’t know what to believe, but he knew what she wanted him to believe.

He felt sad and empty.

She lay twirling his hair around her finger.

–Now everything’s like before, isn’t it? she said.

He thought about it.

–Yes, it is, he said.

Throughout his Selected Stories, Askildsen’s revelatory power lies not in what he shows the reader. In fact, his imagery – the dead dog, the repeated use of woods and overgrowth as metaphors for the dark internal spaces where desire lurks, and, yes, the twirling of hair in the final story – often errs toward the obvious. In all the muted beginnings, middles and endings of this stark, clean-lined, orderly journey into the heart of darkness of the middle-aged (Norwegian) male, it is what is unsaid that resonates long after each final full stop. While the protagonists of these bleak but compelling fictions warily circle their intimacies, the reader sits on the edge of Asklidsen’s veranda of variation, gazing in, unseen, snatching up the glimpses of honest emotion, however dark, preserved in the suffocating amber of dissatisfaction and compromise. It is the compelling central tragedy of all Askildsen’s characters that they, like so many of us, are trapped in situations where ‘nothing is the way it used to be’, yet ‘everything is as before’.

2 thoughts on “Nothing is the way it used to be, yet everything is like before”

Comments are closed.