photo © chris lott, 2013

In her essay, shortlisted for the 2015 THRESHOLDS International Short Fiction Feature Writing Competition, Susmita Bhattacharya makes a connection with ‘Rowing to Eden’ by Amy Bloom.

Comments from the judging panel:

‘In this eloquent and revealing essay, the writer reflects on her own vulnerability and demonstrates how literature has the power to sustain us through the most challenging of circumstances’; ‘a poignant exploration of the power of short fiction to mirror and also to contain the chaos of our lives, while reminding us of the fragile humanity we share’.

*

Susmita Bhattacharya is from Mumbai, India. She received an MA in Creative Writing from Cardiff University. Her debut novel, The Normal State of Mind (Parthian), was published in March 2015. Her short stories have appeared in several literary journals in the UK and internationally, on BBC Radio 4, and have been nominated for the Pushcart Prize. She lives in Plymouth with her husband and two daughters, and facilitates creative writing in the community. She blogs at susmita-bhattacharya.blogspot.co.uk

Susmita Bhattacharya is from Mumbai, India. She received an MA in Creative Writing from Cardiff University. Her debut novel, The Normal State of Mind (Parthian), was published in March 2015. Her short stories have appeared in several literary journals in the UK and internationally, on BBC Radio 4, and have been nominated for the Pushcart Prize. She lives in Plymouth with her husband and two daughters, and facilitates creative writing in the community. She blogs at susmita-bhattacharya.blogspot.co.uk

*

From One’s Own Perspective: ‘Rowing to Eden’ by Amy Bloom

by Susmita Bhattacharya

In the summer of 2014, among all the exciting things that were to happen in my life, like turning forty and launching my debut novel, I was diagnosed with breast cancer. It was so sudden, so random, without any previous symptoms, that I could not even own it.

Through the eight months of intense treatment, the cancer consumed me: physically, mentally and emotionally. I was on a carousel of drugs, side effects, bouncing back and hunkering down again. And one thing that affected me most was that I stopped writing. I had visions of taking to my bed during chemotherapy and writing a tome, considering that I had all the time in the world. Not one word emerged. The brain refused to move out of its chemo-induced fog to indulge in any creativity. So in an attempt to stay engaged with writing, I kept on reading. Books helped me escape to a place that was not ‘here’. I escaped from my prison, my own body, to sunny India, to the inside of a doctor’s mind, and a full American big top romance. I read plenty of short stories, as they were quick to finish and easier to concentrate on.

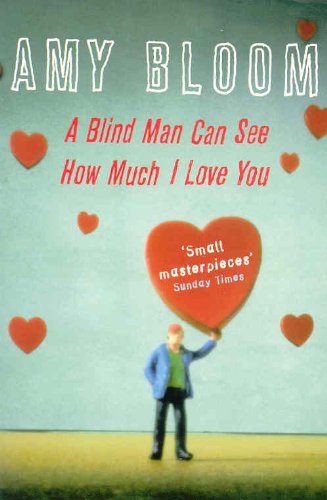

One of the stories that totally understood my situation and me was Amy Bloom’s ‘Rowing to Eden’ from her collection A Blind Man Can See How Much I Love You. Though set in the United States, it managed to connect with me and my cancer experience and I realised that, regardless of geography and culture, the human mind and heart are the same; the complexities of relationships remain.

The story follows the lives of three friends: husband and wife, Charley and Mai, and Mai’s best friend, Ellie. Mai is undergoing treatment for breast cancer, while Ellie was treated for the same a couple of years before. Charley is caught in the crossfire of trying to be helpful and empathetic to Mai and getting in the way.

The story follows the lives of three friends: husband and wife, Charley and Mai, and Mai’s best friend, Ellie. Mai is undergoing treatment for breast cancer, while Ellie was treated for the same a couple of years before. Charley is caught in the crossfire of trying to be helpful and empathetic to Mai and getting in the way.

What makes me connect to this particular story, among all the other cancer stories I read, is the absence of any sentimentality or bleakness. This is a study of human relationships in the face of problems. There is a coldness of facts, and yet the tongue-in-cheek observations of the cancer patient and her carers often produce a mental chuckle. This story brings to life the actual sensations and experiences I went through while having treatment. The chemotherapy ward, no matter how cheerful the nurses and the casual camaraderie between the patients, will always bring a chill to the bone.

…as soon as the saline starts, the fat little bag hung on the curling candelabrum that holds all the drugs, each pouch attached with nursery-blue clips and clamps, clear tubing leading to the pump […] Once they have been through the saline and the Benadryl and the Zoloft, it’s time to get down to business, and the business of Taxol is a small well of fire at the entry point, shooting up Mai’s arm like a gasoline trail.

There are lists, clinical cold lists of all the paraphernalia needed for treatment. Bloom goes into every tedious detail, by which she cleverly indicates the tediousness of the whole process. Once the body is blasted by toxins, the mind cannot function through the chemo-fog and lists become one’s life. Lists of medication. Lists of side-effects. Lists of what to mention to oncologists at consultations. Lists of what to do on good days. Lists of what to do once the treatment is over. I have my lists, on scraps of paper, on an excel sheet, behind supermarket receipts, in my journal. Mai and Elli have their lists too. As does Charley. Lists of stuff to take to the chemo ward. Lists of what Mai can or cannot eat. Do or cannot do. The list of cancer books. The drugs. The lists of women in the waiting room in various stages of hair loss. I love that particular list, because somehow women often grab that opportunity to make a statement.

Women in scarves, women in floppy denim hats, women in good wigs, even enviable wigs, and women in wigs so bad they would look better in sombreros…

Cancer immediately brings on a disconcerting or traumatic side effect – the loss of hair. Given that it will grow back, perhaps in better condition than it previously was, I looked upon it as an experience to make the most of, given I had no choice. So here was my chance to look upon my bald self, try on wigs and scarves and hats and not be daunted by the bald head staring back from the mirror. I became aware of presenting myself stylishly, choosing my clothes and make-up with care. Something I had not bothered with pre-cancer. But Ellie looks at Mai’s bald head and feels bad. And Mai, in her dreams, has a head full of hair and her two breasts intact.

Every time Ellie looks at Mai, she misses her silver-blond braid and is grateful that her eyebrows, narrow gold tail swipes, have held on. Mai’s naked head has a pair of dents halfway up the back, and a small purplish birthmark behind the left ear, and although her skin has amazingly been soft and poreless, the disappearance of her fine body hair is a little jarring to both of them…

But, just beneath the surface of this story, the three characters are involved in an intricate dance: the husband and the best friend trying to possess Mai, owning her illness, trying their best to make it better… and failing.

Bloom’s training as a social worker and psychotherapist has definitely influenced her in writing a story that brings out emotions and subconscious actions without the need for words. Though she says in an interview with Richard Godwin, on The Slaughterhouse, that her profession does not help her with the actual writing, it has allowed her to ‘listen to people talk, to refrain from interrupting them, and to resist jumping to conclusions’.

Bloom’s training as a social worker and psychotherapist has definitely influenced her in writing a story that brings out emotions and subconscious actions without the need for words. Though she says in an interview with Richard Godwin, on The Slaughterhouse, that her profession does not help her with the actual writing, it has allowed her to ‘listen to people talk, to refrain from interrupting them, and to resist jumping to conclusions’.

She puts her observations down in words with great accuracy and boldness. So we cringe when Charley ‘puts his hands up in the air and clicks his fingers’ every time Mai goes to hospital for chemotherapy. He is not his normal self, forcing himself to look cheerful, be funny for Mai’s benefit. But she doesn’t want to acknowledge his efforts. She ignores him, because ‘the person with cancer does not have to be amused’. She will not look upon her husband’s face, as she doesn’t want to see the vulnerability, the sense of loss that he projects on her. They dance around the cancer, refusing to talk about it, to make it a part of their reality. Their relationship is being tested as they have not been intimate since the diagnosis. ‘The privilege of cancer is that Mai is allowed to close her eyes, as if she is all worn out from surgery and chemo, and not look at Charley’s lonely, frightened face.’

How true those words. Cancer becomes the excuse – one size fits all, for everything. One can curl up into a shell, lock the world outside and live on an alternative planet. No one is allowed in there, because suddenly the only person one is aware of is oneself. The body and the mind points inwards, through aches and pains, though anxiety and fear; one looks out for oneself. Others come second.

And then there’s Ellie. Years of friendship with Mai make her believe she is more in charge of Mai than Mai herself. And since she has experienced the same cancer before, she believes she is qualified to be in charge. Also, being a lesbian gives Ellie the permission to be close to Charley, to not bother with social etiquette on how to behave with the best friend’s husband because it-is-safe-I-am-a-lesbian.

Charley and Ellie have their own unique relationship. In fact, they seem to be more comfortable in each other’s company than with their respective partners because both of them are happy to sit back and watch their partners take action.

It was with Charley, not Mai, that Ellie dressed the comatose football captain in drag and tied him to his bed; it was Charley and Ellie wading through Thomas Hardy and toasting marshmallows while Mai and Ellie’s girlfriend skied Mount Snow until dark; and even now it is Charley and Ellie dancing for hours at endless Cushing weddings and anniversaries.

Charley and Mai cannot have an open conversation about her illness and, in the end, Charley turns to Ellie, Mai’s best friend and his partner-in-crime for most things, to talk about Mai’s condition and to see, for the first time, what the scar looks like, to touch the ‘red-blue braid of scar tissue’, to superimpose Mai’s image onto Ellie and kiss her wound. Here, at last, Mai and Ellie merge into one, and Charley can hold what he cannot have. Mai has so far refused to show him her naked body and Ellie is the pathway to Mai’s agony. Her illness. Her shame.

And with this, Bloom creates a mirror image. I find myself looking at me. How I must have shut out my loved ones, spiralling into my own illness and self-absorption. And with this, Bloom also shows me that everything is not black and white. We are all human beings giving into weakness, to illness. And it’s alright. In the end, we are not perfect. We have to make do with what we can, in order to survive.