photo © Rebecca Peplinski, 2010

In his essay, shortlisted for the 2015 THRESHOLDS International Short Fiction Feature Writing Competition, Stephen Devereux finds hints of Tennessee Williams’ personal life in his story ‘The Resemblance between a Violin Case and a Coffin’.

*

Comments from the judging panel:

‘Highly engaging with a mature insight into the work of Tennessee Williams’; ‘a well-crafted and polished essay’; ‘a subtle and nuanced enquiry, which offered me a fresh glimpse of Williams’ daring on the page and his achievement as a story writer’.

*

Coming Out in Print: Tennessee Williams’ ‘The Resemblance between a Violin Case and a Coffin’

by Stephen Devereux

It is almost half a century since I first read Tennessee Williams’ Collected Stories. There was much in them that I did not understand then, but some of the language and images remained with me, somehow. One of those blurred images was of a violin case that was said to resemble a coffin. I have read several of those stories again recently; it was like seeing a half-remembered landscape from a distance.

Tennessee Williams’ prose pieces are little read today. Maybe his output as a dramatist is so celebrated, so frequently performed, that it entirely overshadows his short stories. Those readers and critics who are aware of Williams’ fifty or so short stories tend to regard them as either preliminary sketches for his plays, or little more than an autobiography presented in short story form. It is true that several of the stories have the seeds of the plays within them. The Night of the Iguana, for instance, was a short story before it was rewritten as a play. Many of the stories do, indeed, make use of subject matter that parallels Williams’ life and experiences, but this is equally true of his plays. Ultimately, critical neglect banishes what is unread to obscurity. With this essay I’m doing my bit to drag a little morsel of Tennessee Williams’ prose back into the light.

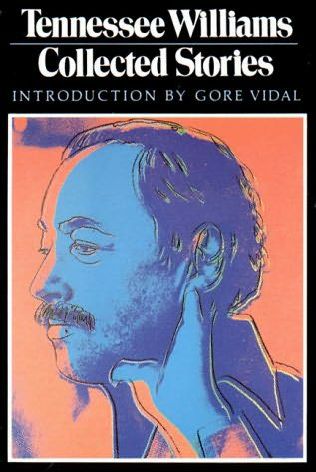

Williams rarely makes use of narrators whose voice is distinct from his own. His narrators are storytellers who drop down from the lofty, detached safety of omniscience to share with the characters their hopes, their delusions, their anguish and their failings. In the introduction to Collected Stories, Williams’ long-time friend and lover Gore Vidal puts it more boldly: ‘No, he is not a great story writer like Chekhov, but he has something rather more rare than mere genius. He has a narrative tone of voice that is totally compelling.’ His story ‘The Resemblance between a Violin Case and a Coffin’ was one of those that puzzled me so long ago. Reading it once more validated Vidal’s insight.

The young boy in the story is called Tom, which was Williams’ real name, and he lives, as did Williams, with his sister, his mother and his grandparents. Although never stated, the narrator’s voice is clearly that of Tom as an adult. From the outset, this is a rite of passage piece that looks back tenderly at Tom’s tortuous realisation  of the nature of his sexuality. Or, it might be truer to say, his realisation of the nature of sexuality, since much of the story is also taken up with Tom’s sister’s coming of age. In the story, she is never named but is undoubtedly closely modelled on Williams’ sister Rose, who was the inspiration for several of his characters, most notably Laura Wingfield in The Glass Menagerie – also both a story and a play.

of the nature of his sexuality. Or, it might be truer to say, his realisation of the nature of sexuality, since much of the story is also taken up with Tom’s sister’s coming of age. In the story, she is never named but is undoubtedly closely modelled on Williams’ sister Rose, who was the inspiration for several of his characters, most notably Laura Wingfield in The Glass Menagerie – also both a story and a play.

From the other side, now, of the revolution that transformed attitudes towards sexuality, some of Williams’ formulations and circumlocutions seem coy, evasive even, to modern readers. However, the euphemisms, the dualities and hyperboles in ‘The Resemblance between a Violin Case and a Coffin’ actually succeed in conveying far more convincingly the young Tom’s uncertainties and desires than the politically correct, unambiguous language of today could. Tom the child cannot be more explicit about his desires since he does not comprehend them. The adult Tom, however, knows what his younger self did not, so it is the child’s attempt to understand himself that is so poignantly expressed. At the moment of writing, the adult grapples with the emotions and events that formed him in childhood. We explore this double perspective through Tom’s spying on his sister’s violinist friend as they practise a duet. The adult Tom asks:

How on earth did I explain to myself, at that time, the fascination of his physical being without, at the same time, confessing to myself that I was a little monster of sensuality?

His sister’s coming of age works as a kind of cover for young Tom’s realisations about himself. She is two years older and has been Tom’s playmate, his only friend. One morning she appears to him to be utterly transformed. Her mother and grandmother begin to treat her in an entirely different way:

She was escorted to the kitchen table for breakfast as if she were in danger of toppling over on either side, and everything was handed to her as though she could not reach for it.

Tom is never told and never guesses, in this matriarchal household, that his sister has experienced her first menstrual cycle. Tom must discover that she is no longer allowed to play in the yard with him, that he must knock before entering her room, and that he has been cut off, both physically and imaginatively, from his beloved sister and the world they had inhabited. His confusion over the transformation of his sister foreshadows his own confusion over his sexual identity later in the story. Although his sister’s transformation is never explained, it is surrounded in ritual and seclusion, whilst Tom’s must remain hidden.

The language employed by Williams to describe Tom’s sense of separation uses the metaphor of a wounding, along with that of a loss of territory. His sister must leave ‘the wild country of childhood’ to which ‘she had been magically suited’. He describes the ‘protocols’ that now govern his relationship with his sister as ‘the wound [that] turned me inward’. Equally, he feels that the change in his mother’s and grandmother’s attitude towards him is a kind of accusation, as if he had ‘given her a bloody nose or a black eye, except that she wore no bruise, no visible injury’. The imagery of a wounding is used to suggest both his sister’s secret transformation and Tom’s mourning for the loss of her as his sole companion. The lack of any ‘visible injury’ symbolises both the invisibility of the cause of his sister’s mysterious metamorphosis and Tom’s silence in the face of this catastrophe.

Once Tom has accepted that his relationship with his sister has come to an end, the adult Tom describes this as putting away ‘in a box a doll no longer cared for [… that was] the magical intimacy of our childhood together’. This close brother and sister relationship has been frequently re-enacted in Williams’ plays and has provided a rich pasture for psychoanalytical critics to graze.

When Richard Miles comes to the house to practise the piano and violin duet with Tom’s sister, Tom is already in love with Richard because his sister is: ‘She had fallen in love. As always, I followed suit.’ It is not simply that Tom’s love for his now distanced sister is transferred onto Richard, it is his love for her that causes him to see Richard as an object of adulation. This rather improbable explanation, laden with Freudian possibilities, might not have worked with a lesser artist, but Williams’ prose carries it off marvellously. The adult Tom tells us:

Since [my love] was copied from hers, it was probably hers that was greater in the beginning. But while mine was of a shy and sorrowful kind, involved with my sense of abandonment, hers at first seemed to be joyous.

When Tom sees Richard carrying his violin in its case, he is struck by the similarity between the case and ‘a little coffin, a coffin made for a small child or a doll’. The link made here between Richard’s violin case and a coffin recalls the imagined box to which Tom consigned the ‘doll’ of his and his sister’s rapturous childhood.

As Tom secretly watches Richard, his love develops from an idealised to a physical passion. We are presented with several images of Richard, drenched in lyrical, homoerotic visions. The adult Tom remembers what Richard wore:

…a white shirt, and through its cloth could be seen the fair skin of his shoulders. And for the first time, prematurely, I was aware of skin as an attraction. A thing that might be desirable to touch. This awareness entered my mind, my senses, like the sudden streak of flame that follows a comet. And my undoing […] was now completed.

That wonderfully old-fashioned word ‘undoing’ expresses both young Tom’s boyhood shame and the adult Tom’s acknowledgement of the consequences of that boyhood epiphany.

Tom concocts an elaborate method of watching Richard rehearsing with his sister. He lies on the floor of his bedroom and holds the door just two inches open so that his line of sight takes in the parlour below. He has become a voyeur, a Peeping Tom if you will, and the language becomes a little more explicit:

The way that he lifted and handled his violin! First he would roll up the sleeves of his white shirt and remove his necktie and loosen his collar as though he were making preparations for love.

When the time comes for the duet to be played in public, Tom’s sister is so overcome with nerves (and, perhaps, love) that she plays badly, requiring Richard to cover her mistakes. During the performance, Tom experiences a second epiphany: he no longer sees his sister as beautiful:

Her shoulders were too narrow and her mouth a little too wide for real beauty […] her recent habit of hunching made her seem a little like an old lady being imitated by a child.

Does Tom, by seeing his sister in this way, symbolically reject female beauty just as his gaze, earlier had idolised male beauty? So I thought when first reading this story so many years ago. But what of the resemblance between the violin case and a coffin, foreshadowed by the story’s title? I had linked this with the metaphoric ‘burial’ of the ‘doll’ that was Tom’s childhood idyll with his sister, but the story goes quite unexpectedly somewhere else in the last two paragraphs.

Does Tom, by seeing his sister in this way, symbolically reject female beauty just as his gaze, earlier had idolised male beauty? So I thought when first reading this story so many years ago. But what of the resemblance between the violin case and a coffin, foreshadowed by the story’s title? I had linked this with the metaphoric ‘burial’ of the ‘doll’ that was Tom’s childhood idyll with his sister, but the story goes quite unexpectedly somewhere else in the last two paragraphs.

The narrator tells us that Richard Miles ‘faded out of our lives’, that Tom’s sister abandoned her music and the family moved to a northern city. News reaches them of Richard dying of pneumonia. The narrator explains: ‘I am not putting all of these things in their exact chronological order, I may as well confess it, but if I did I would violate my honor as a teller of stories.’ These words trigger a loss of our belief in the narrator’s voice as that of the adult Tom. Now, the voice seems to be that of the professional storyteller, confessing to his manipulation of ‘real’ events. The final unfinished sentence – ‘And then I remembered the case of his violin, and how it resembled so much a little black coffin made for a child or a doll…’ – is horribly frustrating. It’s hard to see how this symbolic resemblance should now be used to symbolise Richard’s death, a death that comes simply as ‘news’. We are never given Tom’s or his sister’s reaction to such disturbing information.

All those years ago, I concluded that there must be some complex aesthetic explanation for the way the story ended that I was just too young to grasp. Now, I see it as a loss of focus that weakens rather than strengthens the cohesion of the narrative told by the adult Tom looking back. We have to accept that this ending was the one Tennessee Williams wanted, though, rather than a throwaway, desperate signing off. This is the ending Williams chose for us.

However, Gore Vidal describes a moment that might throw some light on Williams’ technique. He recounts finding Williams rewriting a story that had already been published. When Vidal asked, “Why rewrite what’s already in print?” Williams replied, “Well obviously, it’s not finished yet.” Obvious to whom, I wonder? Perhaps he regarded every story as unfinished. And now, my older self, still puzzled by that ending, has to confess that he was probably right.