photo © Marco Masciovecchio

by G. F. Phillips

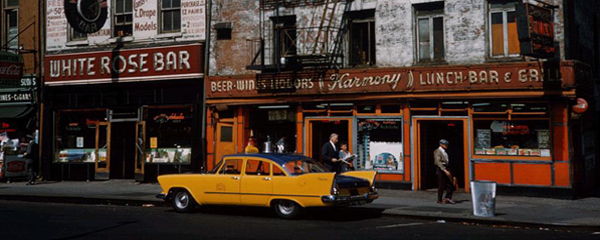

In Raymond Carver’s stories, the character voices tell of the dispossessed, the marginalised, and the American underclass, over a period of twenty-five years, from the early 1960s to the late 1980s. It is a world that conjures up the people’s goal as a means of achieving some kind of ‘American Dream’ in a land made for freedom and plenty. His characters think, speak and act out their shapeless lives, and yet, they share a common language and sense of place, in Carver’s own words, ‘a high premium on clarity and simplicity, not simple-mindedness – which is quite different’. Overall, he tried to make his voices fit the times.

Carver often presents his stories in domestic interiors. As Rene Welleck and Warren Austin suggest, in Theory of Literature, ‘domestic interiors may be metonymic or metaphoric expressions of character’. A good illustration of this can be found in Carver’s story ‘Gazebo’, where the two central characters, a married couple, Duane and Holly, try and run a motel on the back of Duane’s affair with a Hispanic maid, who is in their employment. Previously addicted to alcohol, the couple re-establish their habit, which is no consolation. At continued loggerheads, they talk through their addiction in voices that have lost their sense of direction, value, and higher esteem, only alcohol dulling the pain of Duane’s indiscretion. Duane’s internal voice observes how they manage their live-for-today, inebriated lives. First, he admits he has stopped cleaning the pool, then he stops fixing the faucets, or laying more tiles, or touching-up painting, all because ‘booze’ has got the better of him. Equally, Holly cannot cope with registering the guests properly and seeing to their room service, so much so, that the motel begins to lose custom. After a catalogue of mismanagement, the complaints pile up and the downward spiral intensifies:

The next thing, there’s a letter from the management people.

Then there’s another, certified.

There’s telephone calls. There’s someone coming down from the city.

But we had stopped caring, and that’s a fact. We knew our days were numbered. We had fouled up our lives and we were getting ready for a shake-up.

Holly’s a smart woman. She knew it first.

Duane’s acknowledgment that ‘Holly’s a smart woman’ illustrates how she has a greater insight and awareness of their precarious state before he does. Carver’s use of idiomatic speech shows that his stories are character-led; they learn from first-hand experience. The learning experience here comes in the form of an epiphany. Duane’s foreshadowing – ‘we were getting ready for a shake-up’ – suggests that he is speaking not only about himself but also for Holly. In fact, the epiphany comes in the form of Holly’s memory: she tells how once they drove off the road and up to an old farm to ask for a drink of water. An elderly couple – a farmer and his wife – oblige and they have some cake, as well. Holly remembers more and questions Duane about it:

… later on they showed us around? And there was this gazebo there out back? It was out back under some trees? It had a little peaked roof and the paint was gone and there were these weeds growing up over the steps. And the woman said that years before, I mean a real long time ago, men used to come around and play music out there on a Sunday, and the people would sit and listen. I thought we’d be like that too when we got old enough. Dignified. And in a place. And people would come to our door.

Both the gazebo and the motel are architectural metaphors of the couple’s emotions. The gazebo is a reflection of the way they have treated the running of the motel, with its paint peeling and weeds overgrown. It also reflects the state of flux in which they are living. As for the motel, Holly has lost interest in it because of Duane’s infidelity. Likewise, Duane’s lack of interest in it’s economic potential is because his mistress is still uppermost in his thoughts. The gazebo prompts Holly’s acute remembrance of a happy time together with Duane. The crucial word here is ‘dignified’. Holly has seen in the elderly couple how their future could have been; cultured, safe and secure in their own property – utterly respectable, instead of its present haze, antagonistic and impoverished.

Both the gazebo and the motel are architectural metaphors of the couple’s emotions. The gazebo is a reflection of the way they have treated the running of the motel, with its paint peeling and weeds overgrown. It also reflects the state of flux in which they are living. As for the motel, Holly has lost interest in it because of Duane’s infidelity. Likewise, Duane’s lack of interest in it’s economic potential is because his mistress is still uppermost in his thoughts. The gazebo prompts Holly’s acute remembrance of a happy time together with Duane. The crucial word here is ‘dignified’. Holly has seen in the elderly couple how their future could have been; cultured, safe and secure in their own property – utterly respectable, instead of its present haze, antagonistic and impoverished.

Carver liked to begin his stories with some present crisis. In ‘A Serious Talk’, a household object hints at an ambiguity of feeling in the broken relationship between Burt and Vera: ‘[Her] ashtray was not really an ashtray. It was a big dish of stoneware they’d bought from a bearded potter on the mall in Santa Clara.’ The brevity of the single adjectives that describe both the potter and the ashtray evoke the bleakness of the couple’s relationship.

More than anything, Carver will take the reader to the crunch time in any relationship. Timing is everything. In ‘Will You Please Be Quiet, Please’, Marian is busy ironing, while Ralph is contentedly lounging, when she confesses her past affair at a party to him, probably feeling secure in the knowledge of their long-term relationship. After a few exchanges, he raises the tempo: ‘“Christ!” The word leaped out of him. “But you’ve always been that way Marian.” And he knew at once he had uttered a new and profound truth.’ This sudden outburst hints that he had kept silent about it all along. Silence can highlight a hidden conflict, which is what we see in Ralph.

Carver’s stories also deliver noisy arguments. In the story ‘Little Things’, an ironic duologue takes place between the mother and father of a baby:

She would have it, this baby. She grabbed for the baby’s other arm. She caught the baby around the wrist and leaned back. But he would not let her go. He felt the baby slipping out of his hands and he pulled back very hard. In this manner the issue was decided.

The antagonism at play here is one of self-preservation, often shown in Carver’s stories as something unresolved, even in his endings. In ‘Little Things’, there is stark contrast between the interior and the exterior. From the beginning, the location sets up the narrative: the outside is seen through a window; the snow turns to rain; the dark outside invades the darkness of their relationship inside the house. There is as limited scope for the story as there is with their relationship, because it could be anyone’s domestic row, and that is surely Carver’s point.

Both silence and argument are ways for Carver’s characters to offset the dull routine of their lives, where vulnerability and insecurity lie just under the surface. He is open about their drug-taking, alcohol abuse, and broken marriages, avoiding sentiment and highfalutin prose. These voices of impoverishment, a silent  minority, can all too easily be out-argued and, as a consequence, be outvoted.

minority, can all too easily be out-argued and, as a consequence, be outvoted.

For Carver, the self can be a microcosm of American social prejudice and attitude. There is the all-embracing voice of postman Henry Robinson, in ‘What Do You Do in San Francisco?’, for example – a man who knows everyone’s business in the neighbourhood and so has outspoken verdicts on their personal narratives. His viewpoint comes from a position of strength, out of a sense of duty, and is endemic of the character’s mood. In this story, Henry has gained a particular insight into one young man on his round; his sermonising could be a counterblast against the unemployed in general:

I’m not a frivolous man, nor am I, in my opinion a serious man. It’s my belief a man has to be a little of both these days. I believe, too, in the value of work – the harder the better. A man who isn’t working has got too much time on his hands, too much time to dwell on himself and his problems.

Henry speaks for the everyman – whether the ‘frivolous’, or the ‘serious’ person – about what is expected from an individual, with his ‘work-hard-and-it-will-bring-you-rewards’ thinking. Such is the nature of the postman’s job: he can pass on and reinforce his own prejudice through gossip, thereby belittling the voices on the margins, the impoverished.

So it is that dialogue is an important marker in Carver’s stories. He chooses the natural brevity of everyday speech, where everyone has his or her own lexis. In ‘Nobody Said Anything’, a boy narrator meets a kid on a fishing trip. His rival’s perception is put to the test when the narrator decides to share a trout they both thought they had caught:

I handed the kid the tail part.

“No,” he said, shaking his head. “I want that half.”

I said, “They’re both the same! Now goddamn, watch it, I’m going to get mad in a minute.”

“I don’t care,” the kid said. “If they’re both the same, I’ll take that one. They’re both the same right?”

“They’re both the same,” I said. “But I think I’m keeping this half here. I did the cutting.”

The battle continues. The kid says he saw it first. The boy narrator says it was his knife that cut it. In the end, the narrator has a suggestion:

“I got an idea,” I said. I opened the creel and showed him the trout. “See? It’s a green one. It’s the only green one I ever saw. So whoever takes the head, the other guy gets the green trout and the tail part. Is that fair?”

After much studying of the trout, the kid agrees and says:

“You take that half. I got more meat on mine.”

“I don’t care,” I said. “I’m going to wash him off.”

The brevity in the kid’s voice, his picking up of the boy narrator’s phrase ‘they’re both the same’, the resolute and defiant gesture of ‘shaking his head’, contrasts with the boy narrator’s final persuasive line, which is competitive and to the point. The absurdity is that, equal as they are as peers, Carver makes clear this is about power relations, a struggle for how the loudest of impoverished voices still gets his or her say, regardless of its output or how eloquent it is. When the kid discovers he has more meat on his half of the fish than the boy narrator has on his, he expresses it clearly. But, as far as the boy narrator is concerned, he has resolved the issue.

However, the narrator returns home to another issue: an adult conflict frames the story from beginning to end. The boy narrator’s parents have been arguing about whether the boy’s father has been sleeping around with other women or not. Full of themselves, the parents have no interest in the boy’s captive half fish. The mother sees it as a snake; the father sees it as something worthless to be put in the garbage. In its finality, Carver makes it clear that these impoverished voices, living on the margins, spend much of their time problem solving, which is, ultimately, all about power relations.

~

Gordon Phillips is an Adult Education tutor in Literature on Tyneside. His poems have been published in school textbooks and anthologies like New Angles, Oxford University Press and Enjoying English, MacMillan. His short story, Going Backwards to Go Forwards, was recorded for the audio website, Listenupnorth as well as several of his short poems and prose pieces. Five of his short stories can be read at www.cutalongstory.com He has written articles and book reviews for various magazine including The Good Book Guide and Education Review. Also, he has worked on several collaborations with composers, including a multi-media project with Essex schoolchildren called Five Operas. His most recent project, The Square & Compass, is the setting of sixteen poem to music in the first-ever folksong cycle about the history of St Mary’s Island off the North Tyneside coast. The result is a CD with an accompanying booklet to be released in November 2015 in a joint production between author and composer. In 2011 he won a Northern Voices Award. He is a member of the Society of Authors and the Performing Right Society. More details can be obtained from his website: www.gfphillipswriter.co.uk/