photo © Gustavo Gomes, 2009

by Rajat Chaudhuri

‘Hills Like White Elephants’, ‘The Adventure of a Wife’ and ‘The Lady with the Dog’ are three remarkable short stories about love. But they stand at a distance from the happily-ever-after fairy tale narratives and star crossed lovers of romantic love stories. What ties these stories together and sets them apart from others is an undertow of tension. Tension as a manifestation of the vicissitudes of relationships. The authors of these stories – Ernest Hemingway, Italo Calvino and Anton Chekhov, respectively – explore the ambiguities of relationships, light against dark, setting hope against uncertainties and desperation.

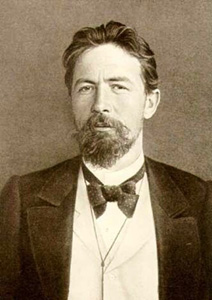

Chekhov’s ‘The Lady with the Dog’ (1899) begins with a chance encounter between two people, Anna Sergeyevna and Dmitri Dmitritch Gurov, both fed up with their conjugal lives. This liaison may or may not transform into love. For Anna, it soon turns to passion laced with guilt, whilst Dmitri, who is twice her age, experiences a slow crumbling of defences. But this is just the beginning. Chekhov evolves both characters, although it is Gurov who undergoes the greatest transformation. Initially incapable of affection, he falls head over heels for Anna. In developing the story further, Chekhov explores the ambiguities of their relationship, employing drama, inner monologues and vivid description.

Chekhov’s ‘The Lady with the Dog’ (1899) begins with a chance encounter between two people, Anna Sergeyevna and Dmitri Dmitritch Gurov, both fed up with their conjugal lives. This liaison may or may not transform into love. For Anna, it soon turns to passion laced with guilt, whilst Dmitri, who is twice her age, experiences a slow crumbling of defences. But this is just the beginning. Chekhov evolves both characters, although it is Gurov who undergoes the greatest transformation. Initially incapable of affection, he falls head over heels for Anna. In developing the story further, Chekhov explores the ambiguities of their relationship, employing drama, inner monologues and vivid description.

Midway through the story we come across a haunting description of the sea. This image of the tireless waves is like a counterpoint to the troubled development of the fledgling relationship between the characters:

At Oreanda they sat on a seat not far from the church, looked down at the sea, and were silent. Yalta was hardly visible through the morning mist; white clouds stood motionless on the mountain-tops. The leaves did not stir on the trees, grasshoppers chirruped, and the monotonous hollow sound of the sea rising up from below, spoke of the peace, of the eternal sleep awaiting us. So it must have sounded when there was no Yalta, no Oreanda here; so it sounds now, and it will sound as indifferently and monotonously when we are all no more.

In the course of the story, nature often presages the mood. Gurov returns to Moscow after Anna has left, and the familiarity of ‘the old limes and birches, white with hoar-frost’ are contrasted with cypresses and palms, which could remind him of ‘the sea and mountains’, and of her.

‘The Lady with the Dog’, which is the longest of these three stories of love, ends without any formal resolution. Gurov and Anna, having found love, stare with trepidation at the difficult and unfamiliar road ahead.

Chekhov, in a letter to publisher Alexei Suvorin, wrote:

You are right in demanding that an artist approach his work consciously, but you are confusing two concepts: the solution of a problem and the correct formulation of a problem. Only the second is required of the artist.

This is what Chekhov does in ‘The Lady with the Dog’. The journey that brings them to the story’s final moment, rife with uncertainty, is what remains with the reader. It is a journey memorable for how it transmutes naked passion into affection and the smouldering embers of love.

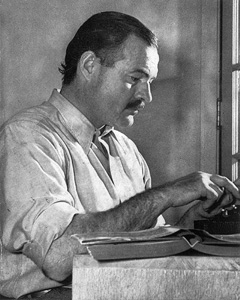

While Chekhov’s story, divided into four sections, has a grand operatic sweep, in Hemingway’s ‘Hills Like White Elephants’ all inessentials are shaved away, leaving something more basic yet memorable and poignant. Hemingway, through the use of crisp dialogue and almost copybook exposition of his iceberg theory, takes us on a different path altogether. He reveals a little about the troubled relationship but he hides more, and meaning in his story is a model of ellipsis and omission.

In this story, Jig and her American lover are taking a train to Madrid, where she is going to have an abortion. The American wants her to have the abortion, while Jig feels nothing will be the same again. The man tries to rationalise the situation and is even prepared to drop the plan if that makes her happy. Jig, however, knows intuitively that a threshold has been breached and what has been lost cannot be reclaimed. While waiting for the train at a rural station, they drink beer and Anis del Toro liqueur.

It is Jig’s innocuous comment that “the hills look like white elephants” – and the man’s response, “I have never seen one” – that brings to the surface the undercurrent of tension in their relationship. Their banter soon deteriorates into a tense exchange of words. While the abortion is not directly mentioned, it gradually becomes clear that this is what they are talking about. The man explains that everything will be ‘fine afterwards’ and Jig reacts with sarcasm. When he says, “I’ve known lots of people that have done it”, she responds, “So have I. […] And afterwards they were all so happy.”

It is Jig’s innocuous comment that “the hills look like white elephants” – and the man’s response, “I have never seen one” – that brings to the surface the undercurrent of tension in their relationship. Their banter soon deteriorates into a tense exchange of words. While the abortion is not directly mentioned, it gradually becomes clear that this is what they are talking about. The man explains that everything will be ‘fine afterwards’ and Jig reacts with sarcasm. When he says, “I’ve known lots of people that have done it”, she responds, “So have I. […] And afterwards they were all so happy.”

As in Chekhov’s story, the landscape emphasises the relationship between the characters. The story begins with a single sentence describing the white hills across the valley of Ebro. A subtle yet powerful description of the moving shadow of the clouds and a glimpse of the river through the trees follows, and this seems to foreshadow the tangible and intangible losses that their relationship will suffer if they go ahead with the abortion. What is also implied in this sharply sculpted story is the inevitable loss of innocence whichever decision they take. The shadow of the cloud gliding across the field is an enigmatic and beautiful image, as well as an evocation of impending darkness.

The girl stood up and walked to the end of the station. Across, on the other side, were fields of grain and trees along the banks of the Ebro. Far away, beyond the river, were mountains. The shadow of a cloud moved across the field of grain and she saw the river through the trees.

“And we could have all this,” she said. “And we could have everything and every day we make it more impossible.”

Echoing Chekhov’s story, uncertainty also plays a part in the resolution of Hemingway’s plot. However, ‘Hills Like White Elephants’ is more ambiguous, in the sense that we do not know whether Jig will finally have the operation. While their tense verbal sparring ends in a sort of reconciliatory tone – with Jig saying, “I feel fine … there’s nothing wrong with me. I feel fine” – there is the lingering possibility that she will not go for the operation, or, if she does, she might leave him anyway. It’s hard to miss the ring of fatalism in those final words; an acceptance of the withering away of love.

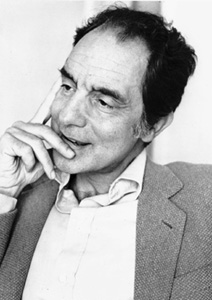

Italo Calvino’s story ‘The Adventure of a Wife’ has a gentler narrative drift. Stefania, whose husband is away, returns to her house early in the morning to find the gates locked. Fornero, the man with whom she spent the night driving in the hills, has dropped her nearby and gone. Before leaving, he had tried to put his arms around her but she stopped him, creating an ambiguity in their relationship.

Now she found the door still locked, and she was alone there in the deserted street, in that early morning light, more transparent than at any other hour of the day, in which everything appeared to be seen through a magnifying glass.

For a moment, Stefania feels a twinge of dismay, but her mood begins to change: ‘…there was something about the early morning air, about being alone here at this hour, that made her blood race not at all unpleasantly.’

She begins to walk towards the neighbourhood bar, which has just pulled up its shutters. She thinks about the night spent driving with Fornero and realises she feels no remorse. ‘Her conscience was easy.’ But has she betrayed her husband by spending the night with Fornero, however innocently? This thought won’t leave her mind, bringing to the fore an emptiness, a lack, in her life as a married woman. It becomes apparent that Stefania didn’t return home because she had been with friends until it got too late, and that she didn’t have the keys. Fornero had driven her around. Although he made advances during the night, she had resisted. Stefania is unsure whether she has crossed a line – maybe it was adultery that she had been looking for?

Before entering the bar, Stefania asks herself, ‘Did she still love her husband?’ and realises that she does, but also that ‘she was a little bit in love with that Fornero’. At the bar she meets three strangers, one after the other: a hunter, a night-owl, and a worker. The hunter wants to take her out for the hunt, the night-owl appears to be curious about her being up at that early hour, while the worker offers her a glass of grappa. It is important to note here that Calvino introduces characters that belong to a different social strata from Stefania, or bear an element of danger, or a life with which she is unfamiliar. The introduction of these characters thickens the mist of uncertainties plaguing Stefania and externalises her inner turmoil.

Before entering the bar, Stefania asks herself, ‘Did she still love her husband?’ and realises that she does, but also that ‘she was a little bit in love with that Fornero’. At the bar she meets three strangers, one after the other: a hunter, a night-owl, and a worker. The hunter wants to take her out for the hunt, the night-owl appears to be curious about her being up at that early hour, while the worker offers her a glass of grappa. It is important to note here that Calvino introduces characters that belong to a different social strata from Stefania, or bear an element of danger, or a life with which she is unfamiliar. The introduction of these characters thickens the mist of uncertainties plaguing Stefania and externalises her inner turmoil.

Calvino, with his quirky yet gentle humour, plays up ambiguities as he leads Stefania through her early morning adventure. What does Stefania really want and does she get it? Has she really betrayed her husband? Is she wracked with guilt when, at the end of the story, she finally manages to get into her house? Calvino hides what drives her, right until the end where a brisk epiphany awaits both Stefania and the reader.

It is evident from our brief survey that these three stories look hard at the tensions that pervade human relationships, each of the protagonists snared in their own very different individual situations. Each plotline, through a journey that is punctuated by ambiguities and internal struggles, leads us towards a climax that is rich with meaning and possibilities. These are stories about the endless mutability of love.