photo by pjotter05

by Kenneth Okpomo

In her review of Helon Habila’s acclaimed novel Measuring Time Melissa McClements posited:

…a crop of exciting new Nigerian writers has emerged in the shaky nascent democracy that followed Abacha’s death in 1998 […] they include Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, author of Purple Hibiscus; California-based political poet Chris Abani; Sefi Atta, author of Everything Good will Come (2005); Uzodinma Iweala, who wrote Beast of No Nation (2005); Caine Prize-winning S.A. Afolabi; and London-based Helen Oyeyemi. And then there is Helon Habila, arguably their leader.

~ from the Financial Times, 9/2/14

Helon Habila was born in Kaltungo in North Eastern Nigeria in November 1967. He tried to study engineering at the Tafewa Balewa University in Bauchi, but was unsuccessful. Following this he resolved to become a writer and gradually committed himself to the writing task. In 1990, he was admitted to the University of Jos where he read English Literature. During his time at university he began to publish short stories and essays.

Habila’s ascendancy into literary fame and stardom did not come by accident or chance; he worked hard for it. In African Writing Online he said, ‘I was always going to be a writer, all my life. I wrote two novels before I turned twenty’. He tenaciously held onto this dream against all odds. When I met him at a 1999 book launch, this young writer exuded an unusual confidence in his literary imbuement. He appeared to me as someone headed for great success and I remember telling other literary enthusiasts to watch out for this writer. None took me seriously, and their reasons were easy to understand. At the time, Habila was working at Hints – Nigeria’s first romance magazine. He did not show any extraordinary promise, and was unable to carve a niche for himself as a romance writer and romantic columnist. The impact of Habila (and other romance writers at that time) was absorbed by the larger-than-life profile of Hints’ editor, Kayode Ajala. Ajala’s vibrant style and overwhelming presence made it difficult for those around him to flourish, and it was not until Habila entered and won the prestigious MUSON Festival Poetry Competition that a turning point in his career was reached.

Habila’s ascendancy into literary fame and stardom did not come by accident or chance; he worked hard for it. In African Writing Online he said, ‘I was always going to be a writer, all my life. I wrote two novels before I turned twenty’. He tenaciously held onto this dream against all odds. When I met him at a 1999 book launch, this young writer exuded an unusual confidence in his literary imbuement. He appeared to me as someone headed for great success and I remember telling other literary enthusiasts to watch out for this writer. None took me seriously, and their reasons were easy to understand. At the time, Habila was working at Hints – Nigeria’s first romance magazine. He did not show any extraordinary promise, and was unable to carve a niche for himself as a romance writer and romantic columnist. The impact of Habila (and other romance writers at that time) was absorbed by the larger-than-life profile of Hints’ editor, Kayode Ajala. Ajala’s vibrant style and overwhelming presence made it difficult for those around him to flourish, and it was not until Habila entered and won the prestigious MUSON Festival Poetry Competition that a turning point in his career was reached.

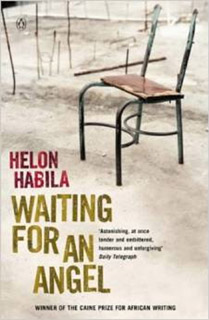

This belief in his creative abilities gave Habila the courage to invest the prize money in the self-publication of his collection of interconnected story stories, entitled Prison Notes. In 2001, Habila entered one of the collected stories, ‘Love Poems’, for the Caine Prize for African Writing and won this prestigious award ahead of numerous established African writers. In 2002, his first novel, Waiting for an Angel, was published by Hamish Hamilton and went on to win the Commonwealth Prize for Best First Novel (Africa Region) in 2003.

Regarded in some quarters as the new Wole Soyinka of Nigerian literature, Habila has now established himself as a formidable writer on the global literary stage. The British Council noted that his work is ambitious in its scope, tackling themes such as politics, corruption, colonialism, coming-of-age, education, history and love. His characterisation is strong and vivid, as is his evocation of both the Nigerian landscape, and the often fragile atmosphere where peace can tip over suddenly into violence.

Many of these themes are encapsulated in ‘Love Poems’. It tells the story of Lomba, a journalist who is falsely accused and arrested by agents of the dictatorial Abacha regime, in the smoldering years of military rule in Nigeria.

When the prison superintendent raids Lomba’s cell, he discovers a carefully concealed roll of papers – Lomba’s secret dairy containing his poems, letters, desultory internal monologues, soliloquies and tortured sentimental effusions to women he had known and admired. Among them, the superintendent finds a poem, ‘Three Words’. He is captivated by it, as it embodies everything he wants to tell a lady he fancies – a teacher, who, he says, has been to the university and has ‘class’, not like other girls. The superintendent re-writes ‘Three Words’ in his own handwriting and presents it to the woman on their first date.

When I hear the waterfall clarity of your laughter,

When I see the twilight softness of your eyes,

I feel like draping you all over myself, like a cloak,

To be warmed by your warmth.

Your flower petal innocence, your perennial

Sapling resilience – your endless charms

All these set my mind on wild flights of fancy:

I add word unto word,

I compare adjectives and coin exotic phrases

But they all seem jaded, corny, unworthy

Of saying all I want to say to you.

So I take refuge in these simple words

Trusting my tone, my hand in yours, when I

Whisper them, to add depth and new

Twists of meaning to them. Three words:

I love you.

The character of Lomba is imbued with a strong survival instinct, and though his body may be imprisoned his mind can still be free – he resorts to writing love poems to old girlfriends and a woman he has never met.

The character of Lomba is imbued with a strong survival instinct, and though his body may be imprisoned his mind can still be free – he resorts to writing love poems to old girlfriends and a woman he has never met.

Depictions of women and love are often integral to Habila’s storylines. During an interview for African Writing Online, Ramonu Sanusi raised the issue about Habila being a feminist, to which Habila responded:

I don’t see myself crusading for the rights of women, but I am also careful never to objectify them or to idealize them […] I grew up surrounded by women, and I learned that they are just as human as any man, so first and foremost I present them as people, not just as women, a people with their strengths and shortcomings and complexities.

Between 1985 to 1998 – a time of despotic military regimes in Nigeria – Habila was just a young boy. The country experienced some hard years when the armed forces were in power. In the same interview with Sanusi, Habila said, ‘I lived through those days and I wanted to write about it, to keep it, as a record of that moment in our history’. In Waiting for an Angel, he talks about the military regime of General Abacha, a disheartening era in Nigeria’s beleaguered political history when journalists were hounded and tried on false charges. The story reflects the brutality of this period, and Habila shows his ability to correlate social realities and creative fiction in an entertaining and compelling way:

“Wait, let me park…” He turns to Lomba. “It is Adam, from the office. He says they just got a report that Dele Giwa has been killed by a bomb.” He turns the car off the road abruptly, veering a bit too far on to the grass verge before coming to a stop.

“Adam, go on. I am listening…”

When he finally puts the phone down, he turns to Lomba. “I don’t believe this.”

Dele Giwa is – was – the founding editor of Newswatch Magazine, and the loudest voice against continued military rule in the country. He was among James’s few close friends. James is staring through the windscreen at the empty road ahead.

“A bomb,” Lomba says, wanting to hear more.

“A letter bomb. It exploded as he unsealed it. He died at the hospital. Bomb. What a way to go,” James says .

[…]

Adam keeps wiping his face with a dirty white handkerchief, and looking over his shoulders through the rear windscreen. He is seated forward in his seat, behind Lomba, his forearm on the back of Lomba’s seat. He still has more to say, “Also, Editor, they said they’ve arrested the editors of the Concord and The Sunday Magazine. Today.”

“All today?”

“Today, sir. You were next in line, sir.”

Lomba’s predicament as a journalist reflects the inherent danger that confronts many Nigerian journalists in the course of their job. As a journalist myself, Lomba’s plight attracted my sympathy.

Habila left his home country in 2002, moving to England to take up an African Writing fellowship with the University of East Anglia – the first of its kind to be established. He later joined the Creative Writing Faculty at George Mason University, Virginia, USA, where he currently teaches Creative Writing and lives with his family. He also teaches on the annual Creative Writing Workshop, led by the Farafina Trust, in his home country of Nigeria – workshops which aim to discover, train and mentor emerging talents in the literary field.