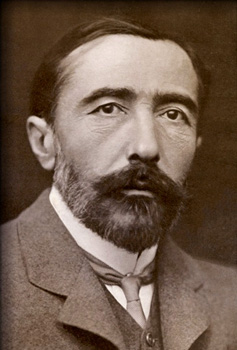

photo by Cinnamon Funch

by Stephen Devereux

Joseph Conrad wrote during a period of dramatic change, in the decades before and after the end of the 19th Century. Where his contemporaries tended to see the new realities that were emerging mostly in terms of status, class, property, manners, urbanisation and industrialisation, Conrad saw colonialism, emigration, cultural conflict, terrorism, crime, revolutions, wars and inter-racial marriage as the topics that should concern writers. His novels and collections of stories were not widely known until after he had written much of his best work. Most are set far from the Victorian drawing rooms of his readers, in remote trading posts in the rain forests of South East Asia, Africa and South American tin mines.

In 1857, Conrad was born in Poland, then under Russian domination. His father was a nationalist who was sent into exile with his family. Orphaned when he was only twelve years old, he decided to go to sea, travelling to Marseille to look for work. He worked on many sailing ships, travelling around the globe, even becoming involved in a smuggling operation for a time. He became a Ship’s Master and only gave up the sea in 1893, after falling ill on a journey up the Congo River. Many of his stories are based on his experiences during this time. He became a British citizen in 1886, but it seems extraordinary that Conrad should have become such a master of the English language, given that he was middle-aged when he was first published and that English was his third language (after Polish and French).

‘Amy Foster’, published in Typhoon and Other Stories in 1903, tells the story of the only survivor of a ship full of East European migrants wrecked off the south coast of England. His depiction of the bodies washing ashore and being laid out in lines by the locals is chillingly similar to contemporary footage of migrants drowned attempting to escape poverty and violence in crowded boats.

‘Amy Foster’, published in Typhoon and Other Stories in 1903, tells the story of the only survivor of a ship full of East European migrants wrecked off the south coast of England. His depiction of the bodies washing ashore and being laid out in lines by the locals is chillingly similar to contemporary footage of migrants drowned attempting to escape poverty and violence in crowded boats.

When we think of a story about survivors coming ashore, what do we imagine? Rescuers waiting on the beach? Warm blankets, hot drinks, ambulances? In Conrad’s take on the familiar story, the survivor comes ashore at night, the locals unaware even that a ship has sunk. He struggles to make his way across muddy marshes and ploughed fields, falling eventually into a pig sty six miles inland. Encrusted with mud, he knocks on doors but is chased away, hit with a whip when he approaches a horse-drawn cart and pelted with stones by schoolboys as he sleeps by the side of the road. The local population see in him whatever they fear most – a tramp, a gypsy, a wild animal, an escaped lunatic. Finally, a farmer (Mr. Smith) knocks him backwards into a woodshed and locks him in. Ironically, he is pleading with Smith for food and water, calling him ‘gracious lord’ in his own language when the farmer assaults him. Time and again, Conrad describes the locals’ hostile reactions to his strange, disturbing language. We are told:

His quick, fervent utterance positively shocked everybody. “An excitable devil,” they called him. One evening, in the tap-room of the Coach and Horses (having drunk some whisky), he upset them all by singing a love song of his country. They hooted him down, and he was pained.

Terrified, he howls in the night, frightening everyone except Amy Foster, the farmer’s servant. She alone believes that there is no harm in him. She creeps out of the house and gives him half a loaf of bread. In the darkness of the woodshed, he kisses her hand. Conrad tells us, ‘Through this act of impulsive pity he was brought back again within the pale of human relations’.

This could easily be a story of how a poor uneducated girl overcomes the xenophobia of a rural community, but Conrad has only just begun. As with many of his novels and stories, he creates a named witness who tells the tale to another. In ‘Amy Foster’, the story is told by Doctor Kennedy, who is accompanied on his rounds by the unnamed narrator who recounts the story. The story begins at the end. Doctor Kennedy calls on Amy, who is a single mother with a young child. Both men agree that she appears to be a ‘dull’ woman who has experienced very little in her life.

As yet, we have been told little of the girl, but Conrad intrigues the reader, hinting at her passionate nature. As the doctor tells her story we learn that, despite appearances, Amy had ‘enough imagination to fall in love […] It was in her to become haunted, possessed by a face’. We are told, ‘She fell in love silently, obstinately, perhaps helplessly’. The narrator draws comparisons to the myths of Ancient Greece and pagans, and the ‘dull’ village girl is transformed by these comparisons into a tragic figure from Antiquity. Doctor Kennedy then recounts to his friend how the castaway came to be on the stricken ship.

The shipwrecked man remains mysterious because he is able to tell his story to Doctor Kennedy only when he has acquired some English. We learn that he is called Yanko (Little John) and that he was a ‘mountaineer’- an inhabitant of the Carpathian Mountains. His father sold some animals and a piece of land to raise the money to send his son to America. Yanko describes a journey he can make no sense of. He travels for many days on a train without knowing what a train is. He sleeps in a glass-roofed building with steam machines coming in and out (Berlin station). Eventually he boards a ship (a wooden platform with trees sticking out of it) and is immediately placed in a dark wooden box (the ship’s hold). He never glimpses the sea and cannot comprehend the violent motions of the box he is in. He does not know the name of the ship or even that ships have names. When he is washed ashore, he has no idea where he is, until he has gained enough English to ask. In this way, Conrad brilliantly defamiliarises late nineteenth Century Europe and readers are compelled to rethink the nature of the world they live in. The impact of this technique is not lost on today’s readers.

The doctor then recalls that there was a storm on the night Yanko came ashore, a storm so fierce that no one on the shore could hear the cries for help. He tells of the bodies washing ashore – the first, a fair-haired child in a red dress. He discovers that the ship was from Hamburg and appears to have been rammed by another ship coming in to shelter from the storm, but which chillingly sails on, unidentified. He speculates that the bodies did not wash ashore straightaway because they were trapped inside the ship, causing the tragedy to remain unnoticed. He reads in a newspaper of others from Eastern Europe duped out of money and land by false promises of fortunes to be made in America. We cannot fail to see parallels with modern day people traffickers.

After Amy gives Yanko the bread, he is allowed to help Mr. Smith, who discovers that Yanko can dig, look after animals and plough. Whilst in the fields, Yanko saves a local landowner’s daughter from drowning in a pond, symbolically restoring to life the little girl washed up from the wreck. The landowner, Mr. Swaffer, gives him a cottage to live in out of gratitude. However, Yanko’s status as a hero does not change the attitudes of those around him.

After Amy gives Yanko the bread, he is allowed to help Mr. Smith, who discovers that Yanko can dig, look after animals and plough. Whilst in the fields, Yanko saves a local landowner’s daughter from drowning in a pond, symbolically restoring to life the little girl washed up from the wreck. The landowner, Mr. Swaffer, gives him a cottage to live in out of gratitude. However, Yanko’s status as a hero does not change the attitudes of those around him.

It was only when he declared his purpose to get married that I fully understood how, for a hundred futile and inappreciable reasons, how — shall I say odious? — he was to all the countryside. Every old woman in the village was up in arms. Smith, coming upon him near the farm, promised to break his head for him if he found him about again.

Now the love story we have been anticipating since the opening is finally told. Yanko is a handsome and athletic contrast to the dour locals. He ‘strives upwards’ whilst the local men seem downtrodden and sullen. Amy is attracted by this difference and he is equally smitten by her. They marry and have a son. While Yanko is frequently described as agile and handsome, Doctor Kennedy is puzzled by his strong attraction to Amy:

I wonder whether he saw how plain she was. Perhaps among types so different from what he had ever seen, he had not the power to judge; or perhaps he was seduced by the divine quality of her pity.

Doctor Kennedy seems to suggest that cultural and racial differences apply even to our perceptions of physical attractiveness.

Happy ever after, then? We now remember that Amy was alone with her child at the beginning of the story. Yanko’s marriage has not meant that he ceases to be regarded as alien. His language continues to disturb his neighbours. He performs a bizarre dance from his native country in the pub and is beaten up for it. His skipping walk, his habit of jumping over styles, only add to his dissimilarity. He is ‘full of good will, which nobody wanted’. When Yanko begins to teach his son prayers in his native tongue, Amy is disturbed by the realisation that her son will grow up speaking his father’s strange language. It becomes clear that even Amy, despite her love for him, is beginning to see her husband as others see him. Doctor Kennedy ‘wondered whether his difference, his strangeness, were not penetrating with repulsion that dull nature they had begun by irresistibly attracting’.

Yanko becomes ill and is tended by the Doctor, but falls into a fever. He speaks angrily to Amy in a way she does not understand. She runs to her parent’s house with her son. In the morning, Doctor Kennedy finds him in the gateway, face-down in a puddle, presumably because he had tried to run after her. The Doctor carries him indoors, covered in mud. Yanko tells the Doctor that Amy has gone, that he was only asking her for water. He has returned to his original alienated condition – muddied, thirsty and misunderstood – and soon after he dies. His final words are “Why?” and “Merciful”. We are left to decide what is implied by these words.

Doctor Kennedy ends by telling his friend that he does not know whether Amy ever thinks about the past, whether her husband’s name ‘recalls anything to her’. What a contrast this is to the language used at the beginning to describe the nature of Amy’s love! Conrad frequently disappoints the expectations he has created in his readers and leaves us with a conundrum. What are we to make of the story? Is it a moral tale, exposing the hostility, the xenophobia of Victorian England? This is how I want to read it, but Conrad, as with all his stories, leaves us with other, more disturbing possibilities. Can the story also be read as a warning that people of different races can never really know each other, even in marriage? His first two novels – Almayer’s Folly and An Outcast of the Islands – have at their centre disastrous relationships between native women and European men, and the theme reappears in other works.

Yanko makes one more appearance in the tale as Doctor Kennedy looks at Amy’s son and sees in him ‘the father, cast out mysteriously by the sea to perish in the supreme disaster of loneliness and despair’. Do we read this to mean that the outsider’s identity persists through genetics? Is Amy fulfilled through having a child to look after? She is portrayed at the beginning of the story as a tender girl, who looks after wounded animals, is meek and is gentle. Conrad withholds from us whether she also sees her husband’s likeness in her child’s face. We don’t know what Amy thinks. She has become the dull girl Doctor Kennedy introduced to his friend at the beginning of the story.

Is the story, perhaps a reflection of Conrad’s own situation? He also frightened his English wife when raving in Polish during an illness. Perhaps the story is about his fear of exclusion, his sense of always being an outsider. Whatever its inspiration, ‘Amy Foster’ disturbs us even more today because the world Conrad depicts remains so shockingly familiar.

This was an excellent piece on Conrad. It was insightful in the way it drew parallels with our current times, and the unemotional factual description of Amy’s story was chilling. It also offered a way into understanding Conrad’s complex thinking of the world and his appreciation of prejudice. Having only read Heart of Darkness, I’m tempted to revisit his work. Thanks Stephen.