photo by Chris Staley

by Marjorie Lewis-Jones

‘Just bury me with some poems and some wattle. I’d like it to be hot.’

~ ‘Red Shoes’, Mark O’Flynn

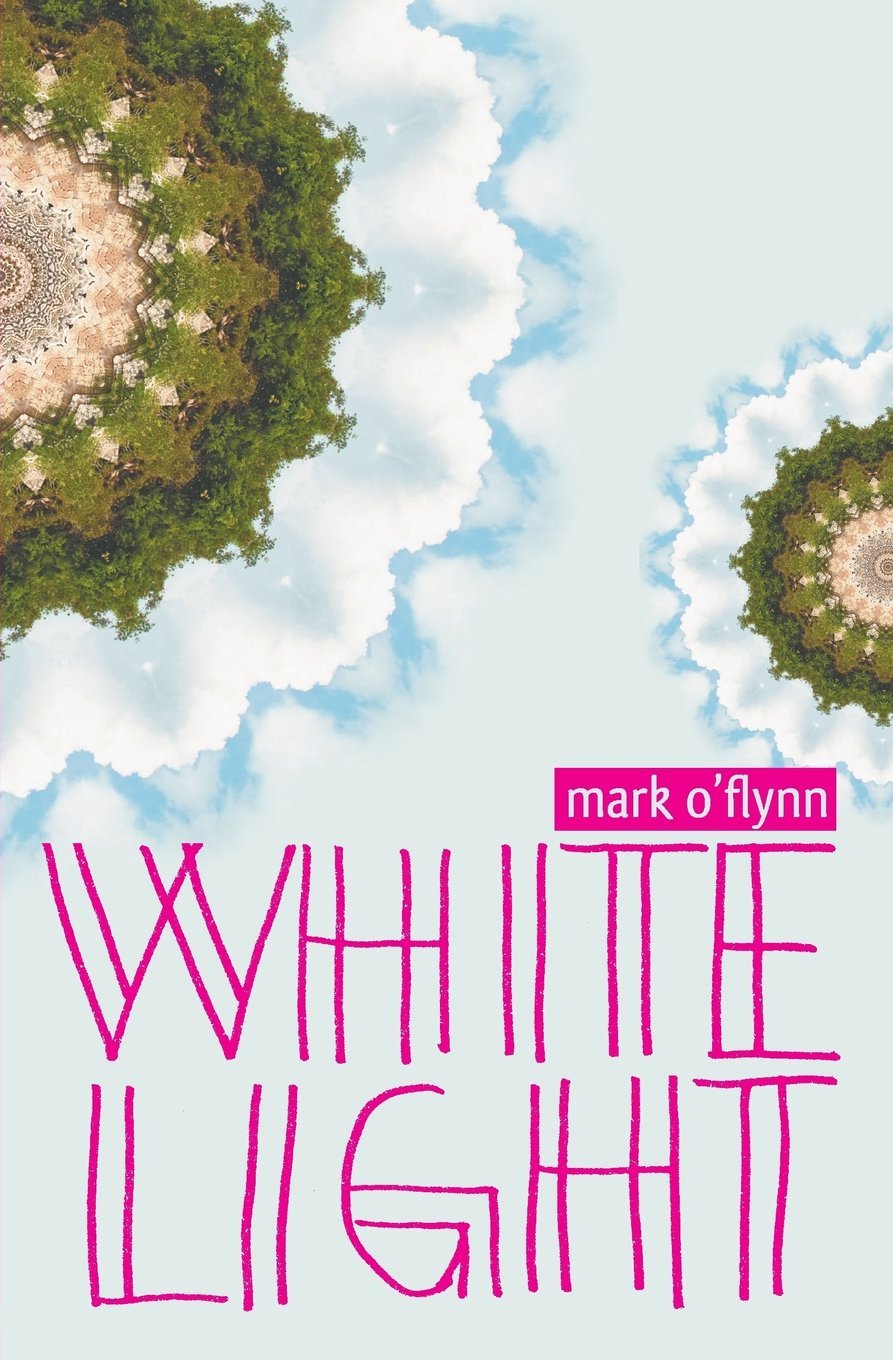

Mark O’Flynn is an award-winning Australian short story writer, poet, playwright, novelist and memoirist with an impressive oeuvre. His short stories simmer with suburban uneasiness, dislocation and melancholy, and voices that are both familiar and eccentric. In his 2013 collection, White Light, there are sixteen of these short works that probe Australian consciousness and connect with universal themes. They also tap the rich vein of comedy that lurks beneath life’s awkward and painful moments.

‘Red Shoes’, the funniest and most poignant of the stories, sees renowned writer Dorothy Hewett get stuck in the railway car toilet while she’s journeying across the Nullarbor Plain to Western Australia, to receive an honorary doctorate. Her husband, Merv Lilley, tries in vain to help her out.

O’Flynn had known Dorothy Hewett in her later years and attended her funeral in 2002. In an interview, published in June on A Bigger Brighter World, he told me: ‘The day … was a scorcher, where so many of us watched Dorothy’s daughters throw the red shoes into the grave.’

The shoes encapsulated much about Hewett’s character. She’d been a Communist, feminist, atheist and sexual libertarian. In the story, the shoes are a striking symbol of how she had aged and lost her strength and vivacity. ‘ “No one wants to see them any more,” she mourns.’

A member of Hewett’s family told O’Flynn about the train incident and, apart from his embellishments, it’s a true story as far as he knows:

The incident had a deleterious effect on Dorothy’s health and, of course, her morale took a battering. Although the situation is slightly bizarre, I still find it moving. I was also trying to remain true to their voices, their integrity.

The Hewett anecdote reveals several significant strengths of O’Flynn’s short stories: slightly odd and yet moving situations; strong and distinct voices; integrity of purpose; striking imagery; humour; and a nugget of truth at the core.

Geordie Williamson, chief literary critic of The Australian newspaper and author of The Burning Library, called White Light a ‘superb collection’. Cate Kennedy, Australian author of acclaimed short story collections Dark Roots and Like a House on Fire (and more), hailed it as dextrous and unique. She wrote:

O’Flynn’s faultless ear for laconic Aussie parlance, his wry ability to turn a story in a moment from comedy to tragedy and back again, his exhilaratingly deft range … all this makes him one of a kind.

O’Flynn was born in Melbourne in 1958 and now lives in the Blue Mountains, west of Sydney; he uses this landscape’s inherent drama to good effect in his writing. His stories, like ‘Beneath the Figs’, give voice to Australian life in suburbia — more sinister than sunny. ‘Bats squeal in the trees, hanging there like great drips of bitumen’, neighbours are ‘clusters of strangers’ and a Plymouth Brethren family rejects advice to take a young girl’s sick baby back to hospital so it can feed.

O’Flynn was born in Melbourne in 1958 and now lives in the Blue Mountains, west of Sydney; he uses this landscape’s inherent drama to good effect in his writing. His stories, like ‘Beneath the Figs’, give voice to Australian life in suburbia — more sinister than sunny. ‘Bats squeal in the trees, hanging there like great drips of bitumen’, neighbours are ‘clusters of strangers’ and a Plymouth Brethren family rejects advice to take a young girl’s sick baby back to hospital so it can feed.

On the surface, ‘Beneath the Figs’ is a story of a neighbourhood divided over whether the local council should cut down the street’s fig trees and move the bat colony out. But the trees and bats symbolise deeper divisions, caused by the wariness of neighbours compelled to live side-by-side in Sydney’s culturally and religiously diverse suburbs. I first read this story many months ago, yet I am still unnerved by the Brethren household and their baby that ‘looks like a bat’, used to show how anxious people can be when faced with difference and the unknown.

O’Flynn teaches English and writing in a New South Wales prison and this ‘perversely inspiring’ environment, as he calls it, seeded several stories in White Light. In ‘Lovely Outing’, an elderly woman, Mrs Lapin, attends a restorative justice session and is prepared to forgive a young man who attacked her. O’Flynn relays the tale much as his student recounted it – namely, how the woman forgave him for attacking her and kept in contact with him. ‘I tried to imagine the situation from her, (the victim’s) point of view, with the aim of trying to raise her above that state,’ O’Flynn said.

Mrs Lapin’s children attend the session, too, and want her attacker punished for being a ‘granny-basher’ and a ‘despicable junkie’. However, Mrs Lapin has come to know the young man through exchanging letters with him and feels their reconciliation will be complete if he can only explain to her why he had betrayed her trust. Why, she wonders, had he eagerly stepped in to help her across the road but then stolen her handbag and knocked her down?

It’s nuanced and bittersweet. The attack had been painful for Mrs Lapin but the connection made with the young man brightened her lonely days.

I’m not sorry Troy that meeting you has meant that I’ve been able to come on this lovely trip to town. I would never have done that otherwise. It’s been so long since I spent such time with my family.

In the story ‘Banjo’, an illiterate inmate learns to read and finds comfort in the poetry of Banjo Paterson. It’s an empathetic portrait that confirms O’Flynn is not interested in exploiting the stories of the offenders he works with, but rather, in a fictional sense, giving them a voice.

‘Banjo’ is a monologue. The criminal telling the story is in jail for what he says is a ‘v. unpopular but also v. common’ crime that has resulted in the other inmates kicking, punching, knifing, pouring boiling water over and trying to rape him. He has tried to kill himself several times.

A fellow inmate reads Banjo Paterson’s poems aloud to the man and eventually he talks to him about his crimes. Through poetry and conversation, the main character recognises jail is actually good for him, as it’s a place where he can further understand his mistakes and continue to pay for them. He learns to read and write and no longer wants to commit suicide.

The story shines a spotlight on to the hard work involved in reformation. Instead of condemning a criminal, we feel compassion for a flawed individual struggling to start over.

I don’t know why people laugh when I say Banjo Paterson saved my life. Every person has to try and live no matter what they be. Every person’s story is different and in time I will be one of them.

In other stories, O’Flynn treads the knife-edge of comedy and seriousness with consummate skill. ‘The Isthmus’ is a story in which two grey nomads (travelling retirees) get stuck on one of the Apostles (off shore rock stacks in Victoria) when a rock arch between it and the mainland collapses. While the couple waits for the rescue helicopter, the distance between them yaws:

We could not be more estranged if we were on a desert isle in the middle of the Pacific with a lone palm tree between us. I wonder if I could push him off the edge and blame it on the wind, but there appear to be too many witnesses with telephoto lenses.

In ‘Bridie’, a soupçon of humour intensifies the story’s pathos. Late one night, as Dean waits with Bridie for her mother to return home, he recalls that she had once attempted to show her pet albino rat to his daughter.

“What happened to your pet rat?” he asked.

“It ran under the couch and all the other rats that live there killed it.”

Dean looked at the couch. It had an aura, he thought, of many things.

A few weeks later, when Dean sees the couch and other household items piled by the roadside, he wonders if Bridie’s mother’s boyfriend has gone berserk and chucked everything out. ‘But no — there was Bridie, amidst boxes, behind a sign proclaiming 4 Sal.’

A few weeks later, when Dean sees the couch and other household items piled by the roadside, he wonders if Bridie’s mother’s boyfriend has gone berserk and chucked everything out. ‘But no — there was Bridie, amidst boxes, behind a sign proclaiming 4 Sal.’

O’Flynn’s confidence in blurring the boundaries between comedy and tragedy comes from a sense that this is how life works. Amid despair the ridiculous happens. In a comic moment there are often dark thoughts. Such ‘multidimensionality’, he said, offers an opportunity to pull the rug out from under the reader, to thwart expectations. Awkwardness, social clumsiness, embarrassment and ineptitude become points of departure in his stories — human frailty used as fuel that propels.

Irish writer, Frank O’Connor, called the modern short story ‘the lonely voice’, and isolation and detachment are themes O’Flynn returns to again and again in White Light. His preference for first person narrative allows him into his characters’ heads with all their limitations and flaws. The conflict of being misunderstood helps build dramatic tension. It’s in this isolation — and amid all of a character’s idiosyncrasies and alienation — that readers will find what he calls ‘a human thread’.

O’Flynn said the commitment of small publishing houses, like Spineless Wonders, to publishing quality short stories was vital in safeguarding the future of the short story in Australia. ‘The short story’s not dead,’ he told me, ‘not even close.’ But it is tidal.

Readers come and go from stories, like they do from novels or non-fiction. Readers aren’t always purists. Short fiction is [often] less commercial, so perhaps the readership is more discerning.

Be discerning: read White Light.

~

Marjorie Lewis-Jones is a Sydney-based writer and editor who blogs about books and writing at www.abiggerbrighterworld.com. Her story ‘Shooting Star’ was published in 2013 by Australian short story specialist publisher Spineless Wonders.