photo by Jose Chavarry

by Tess St Clair-Ford

Sometimes you stumble across a name – a writer, an artist – and it’s like a window opening, a first gust of fresh air blowing in. Carson McCullers was, for me, one of those names.

I first discovered Carson McCullers in an unexpected place: a book called Love, Nina – an epistolary account of life in 1980s London. The sentence read: ‘Carson McCullers: they found Mrs Langdon unconscious, she had cut off her nipples with garden shears.’ Needless to say, I was intrigued.

The author of the often hilarious letters collected in Love, Nina is Nina Stibbes. While working as a nanny for a rather literary family, she began a literature degree at Thames Poly and decided on Carson McCullers as the subject of her dissertation.

In a letter to her sister, Stibbes describes her plan to show McCullers as ‘a brave young writer who had the guts to illuminate a less glossy side of USA life in her stories about deaf people, poor people, kids who can’t write and isolated people’. In her dissertation, Stibbes explores the writer’s life – reclusive and isolated, resented by the critics, unhappily married and committed to representing the under-represented. However, this narrative, as Stibbes discovers, is just one of two conflicting tales of McCullers’ life. The other is perhaps a happier account of a woman now considered to be one of the most significant American writers of the 20th century.

I put down Stibbes’ book of letters and began reading McCullers’ own work. I discovered that the painful nipple image, above, was a quotation from McCullers’ second novel, Reflections in a Golden Eye. I also discovered the writer’s remarkable short stories.

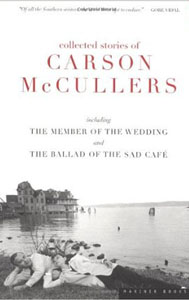

At first glance, the story of McCullers’ life has everything a researcher could hope for: conflicting critical views; early critical acclaim; the war years spent in a Brooklyn artists’ commune; a stormy marriage; rumours of bisexuality; heavy drinking; health complicated by childhood illness; and an early death. Yet at the heart of all this interest, with its potential for the kind of romantic treatment we usually reserve for Hemingway and other American émigrés, is the writing. In amongst five novels, two plays, poetry and over two dozen non-fiction pieces are these beautiful, stark short stories.

At first glance, the story of McCullers’ life has everything a researcher could hope for: conflicting critical views; early critical acclaim; the war years spent in a Brooklyn artists’ commune; a stormy marriage; rumours of bisexuality; heavy drinking; health complicated by childhood illness; and an early death. Yet at the heart of all this interest, with its potential for the kind of romantic treatment we usually reserve for Hemingway and other American émigrés, is the writing. In amongst five novels, two plays, poetry and over two dozen non-fiction pieces are these beautiful, stark short stories.

McCullers was born Lula Carson Smith in Georgia in 1917. Although she left for New York in 1934, her work would always be associated with the American Deep South – an area which, in my imagination, is imbued with overgrown gardens, sultry verandas and the American equivalent of crumbling aristocracy. I’m not sure that McCullers’ childhood fits this picture; her father owned a jewellery store. Young Lula’s life was coloured by her early dedication to music and a misdiagnosed and untreated case of rheumatic fever, which would cause a series of strokes in later life.

In her atmospheric short story ‘Wunderkind’ (1936), McCullers explores the title’s ambivalent label – something she’d come to know only too well, being heralded a ‘wunderkind’ by critics following the publication of her first novel, The Heart Is A Lonely Hunter, in 1940, when she was just twenty-three. A label description to live up to.

In the story, the 15 year old protagonist experiences a mix of terror and admiration for her piano teacher: ‘She wanted to reach out and touch his muscle-flexed finger that pointed out the phrases, wanted to feel the gleaming gold band ring and the strong hairy back of his hand.’ As the story develops, her teacher’s attitude changes. Where he once recognised her as a kind of prodigy, he now struggles to conceal his disappointment in her musical ability. Unmistakeably the work of a young writer, the story is infused with the awful awareness of puberty, of the lost opportunities heralded by becoming an adult.

Like all of McCullers’ characters, the young pianist is an outsider; a Gentile in a musical world dominated by Jews. Perhaps this recurrent and powerful sense of the outsider originated in her tumultuous relationship with husband James Reeves McCullers. Both heavy drinkers, they married young and both engaged in homosexual affairs. In McCullers’ 1951 novella, The Ballad of the Sad Café, she explores the complicated dynamic of a love triangle. It is easy to draw a parallel with her own experience. In the spring on 1941, both McCullers and her husband fell in love with American composer David Diamond. By the end of that year, the couple were divorced.

Their saga continued, however: they remarried in 1945 and embarked for Europe with their literary circle, an illustrious set which included Tennessee Williams and W.H. Auden. But Reeves McCullers was to become increasingly and dangerously depressed. In 1953, he entreated McCullers to join him in committing suicide. Fearing for her own safety, McCullers returned to the United States without him. In November of that year, news arrived that Reeves McCullers had killed himself in a Paris hotel room.

In the midst of this personal turmoil, however, McCullers was enjoying widespread critical success. Living in February House in Brooklyn Heights, she was very much at the centre of a Bohemian literary set. She enjoyed enormous commercial success with the theatrical adaptation of her novel, The Member of the Wedding, which won the Drama Critics’ Circle Award in 1950. Her friends and artistic collaborators from that time form an enviable who’s who: Truman Capote, Benjamin Britten and Gore Vidal. It is no wonder successive critics have questioned the widely held idea of McCullers as the consummate outsider.

However, the long struggle with physical illness presents a grim parallel to her artistic success. Her childhood illnesses left her weakened and in 1947, aged just thirty, she suffered two strokes, only months apart, which left her paralysed down one side. The fallout from this annus horribilis was profound – McCullers attempted suicide in 1948 and struggled with depression for the rest of her life.

This melancholy seeps into her writing. The short story ‘The Sojourner’, published in 1950, is in some ways characteristic. Striking imagery brings a classic New York to life, where ‘pale sunlight sliced between the pastel skyscrapers’. We glimpse again a recurrent theme of music, as the protagonist’s ex-wife, with whom he shares an awkward supper, is an accomplished pianist. But the writing is suffused with sadness and sorrow – the title is an alternative, and preferable, term for ‘expatriate’, but the eponymous ‘sojourner’, John Ferris, regrets all that he has left behind. His short stopover in New York forces him into ‘the acknowledgement of wasted years and death’. The reader, too, shares something of this realisation.

This melancholy seeps into her writing. The short story ‘The Sojourner’, published in 1950, is in some ways characteristic. Striking imagery brings a classic New York to life, where ‘pale sunlight sliced between the pastel skyscrapers’. We glimpse again a recurrent theme of music, as the protagonist’s ex-wife, with whom he shares an awkward supper, is an accomplished pianist. But the writing is suffused with sadness and sorrow – the title is an alternative, and preferable, term for ‘expatriate’, but the eponymous ‘sojourner’, John Ferris, regrets all that he has left behind. His short stopover in New York forces him into ‘the acknowledgement of wasted years and death’. The reader, too, shares something of this realisation.

At midnight Ferris was in a taxi crossing Paris. It was a clouded night and mist wreathed the lights of the Place de la Concorde. The midnight bistros gleamed on the wet pavements. As always after a transocean flight the change of continents was too sudden. New York at morning, this midnight Paris. Ferris glimpsed the disorder of his life: the succession of cities, the transitory loves; and time, the sinister glissando of the years, time always.

It is worth taking a moment to look up the many photographs of Carson McCullers that have survived. Her eyes are wide and sad, and few photographs show her without a lit cigarette in her hand or between pursed lips. She wears tailored shirts and her haircut is sharp and fashionable. There is something boyishly attractive about her, something glum. Director John Huston captures her fine mixture of physical frailty and powerful will when he describes the first time he met McCullers in his autobiography, An Open Book:

She was then in her early 20s, and had already suffered the first of a series of strokes. I remember her as a fragile thing with great shining eyes, and a tremor in her hand as she placed it in mine. It wasn’t palsy, rather a quiver of animal timidity. But there was nothing timid or frail about the manner in which Carson McCullers faced life. And as her afflictions multiplied, she only grew stronger.

There are many contradictions in our portrait of McCullers: terrible weakness and strident strength; a famously ‘Southern’ writer who lived in New York; an outsider who was at the centre of a vital artistic community. When a final stroke killed McCullers in 1967, her funeral glittered with celebrity friends and fans. In her obituary in the New York Times, Eliot Fremont-Smith wrote of the ‘terrible juxtaposition of love and aloneness, whose relation was Mrs. McCullers’s constant subject.’

It is the themes of ‘love and aloneness’ that are the defining bedfellows of McCullers’ stories. Always present in McCullers’ work is an overwhelming sense of sadness, of place, of loss and of threads left untied. In stories such as ‘The Jockey’, readers might be prompted to ask, “Is this the end of the story?” This unfinished quality is far from a failure in the writing. It is, instead, a brave reflection on life, which leaves questions unanswered – like that of the ex-wife’s son, Billy, in ‘The Sojourner’ who asks, in shock and bewilderment, how his mother and their supper guest could have been married. His questions are taken away, unanswered, into another room of their New York apartment.

“Daddy, how could Mama and Mr. Ferris—” A door was closed.

This is the real aftertaste of Carson McCullers’ short stories, her real legacy: a feeling of dissatisfaction and mystery. A sense that you, too, have been pushed to the margin.