photo by Paul Williams

by Erinna Mettler

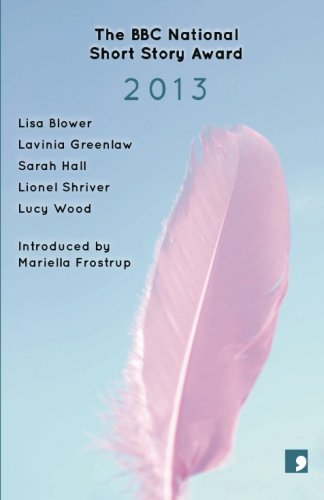

I first came across Sarah Hall’s prize-winning tale ‘Mrs Fox’ on BBC Radio 4 – as part of the grown-up storytelling ritual that accompanies The BBC National Short Story Award. The stories shortlisted for the Award are premiered on radio, expertly told by professional actors. I caught Hall’s programme by accident, prompted by a tip off on Twitter, but from the first sentence I listened to ‘Mrs Fox’ in a state of suspended animation. And I know it will remain a favourite.

I was delighted and intrigued by Hall’s erotically poetic tale about the relationship between a married couple, in which the husband is forced out of his complacent state by the wife’s transformation into a fox. It was so earthy I could smell the musk as I listened. This isn’t to say it’s bestially explicit, far from it, it is the suggestion of cross-species coupling that resonates, an animalistic conjuring reminiscent of Angela Carter’s modernised fairytales.

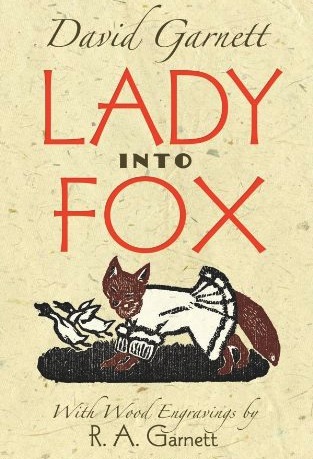

But, when the broadcast was over, there was a brief flutter of outrage on social media. The gist of this was that Hall’s story was overly similar to the 1922 novella Lady Into Fox by David Garnett. I hadn’t read Garnett‘s novella, but ‘Mrs Fox’ was, for me, a short story so perfect in form and content that the merest hint of plagiarism niggled at me and prompted further investigation.

On The Book Trust website, Hall explained that she was inspired by Garnett’s novella, of which she said, ‘my version is a homage to what sounds like a very brave and odd piece of fiction indeed’.

So that’s alright then, a tribute not a rip off. But was it? Was Hall’s tribute sufficiently different from the original to warrant first place in such a prestigious competition? Hall claimed not to have read Lady Into Fox but to have developed the idea from the cover notes and a word of mouth account. Her decision not to read it tells us something of her intentions in writing the piece. She has taken Garnett’s idea and allowed it to develop in her imagination. Despite the formal similarities, Hall’s Fox would be different from Garnett’s in the manner of all word of mouth stories. As she did not read Garnett’s story first hand, she couldn’t help but put her own spin on it.

So that’s alright then, a tribute not a rip off. But was it? Was Hall’s tribute sufficiently different from the original to warrant first place in such a prestigious competition? Hall claimed not to have read Lady Into Fox but to have developed the idea from the cover notes and a word of mouth account. Her decision not to read it tells us something of her intentions in writing the piece. She has taken Garnett’s idea and allowed it to develop in her imagination. Despite the formal similarities, Hall’s Fox would be different from Garnett’s in the manner of all word of mouth stories. As she did not read Garnett’s story first hand, she couldn’t help but put her own spin on it.

There is something tribal about the creation of ‘Mrs Fox’ that sits within the realm of oral tradition and the passing forward of folk tales. Humans in fox form are a common staple of traditional tales the world over and, in a sense, Garnett’s story is itself an homage to these multiple re-tellings. Garnett even repeats the phrase ‘Silvia, Silvia what did you there?’ as if in reference to the children’s nursery rhyme ‘Pussycat, Pussycat’. So perhaps Hall was simply taking up the baton passed from one storyteller to another.

After a little research, I came to realise that Lady Into Fox was beloved of many, but since when did homage detract from the original work? Does Michael Cunningham’s Pulitzer Prize-winner The Hours offend fans of Mrs Dalloway? Is Zadie Smith’s On Beauty invalid because it is a re-imagining of Howards End? Angel Carter said of her most famous short story collection, The Bloody Chamber, ‘my intention was not to do versions but to extract the latent content from the traditional stories’. Having now read both Mrs Foxes, I think Sarah Hall could easily have said the same about her own re-imagining. She adds so much to the original it is hard to know where to begin, so let’s start at the beginning.

From the off, Garnett tells us that the naïve newly-wed, Silvia Tebrick, turns into a fox, and Richard is in awe of his new wife, placing her on a high pedestal. Conversely, Hall establishes the intimate normality of married life before the transformation occurs, and she tells of mutual adoration and sexual fulfilment, though not without a realistic revelation of meaningless infidelities.

There is a more naturalistic quality to Hall’s story; the possibility of transformation is rendered in sensual autumnal descriptions reminiscent of Keats’ season of mists and mellow fruitfulness. Autumn has long been thought of as the season of procreative fulsomeness, and the start of Hall’s tale is located firmly in autumn with its ‘brittle memories of wild garlic and summer flowers’. The wife, Sophia, is sick two mornings in a row, the tell-tale physical signature of pregnancy which usually comes before scientific blue line confirmation. Nausea is often the indication of a body in a state of change before the mind even has time to conjure the possibility. And it is here that Hall’s story differs widely from Garnett’s.

Lady Into Fox seems, to me, to be an allegory of turn of the century social mores, class, propriety and the dangers of transgression, whereas ‘Mrs Fox’ is the most successful depiction of the experience of parenthood I have ever read. I don’t know if this was Hall’s intention, but it was my over-riding impression of what the story was about. Rather than reminding me of Lady Into Fox, it evoked thoughts of Jackie Kay’s ‘My Daughter The Fox’, another tale of fox transformation that addresses the immediate and violent impact of motherhood.

Hall’s Sophia transforms into a vixen before her husband’s eyes:

She turns her head and smiles. There is something wrong with her face. The bones have been re-carved. Her lips are thin and her nose is a dark blade. Teeth small and yellow. The lashes of her hazel eyes have thickened and her brows are drawn together… She has stepped out of her laced boots and is running again on all fours, lower to the earth, sleeker, fleeter.

And a little later, ‘All vestiges shed. She looks over her shoulder. Topaz eyes glinting. Scorched face. Vixen.’

She constantly looks to her husband for support, despite his separation from her transformation. He is not the one changing, yet he is complicit in her change, as all new fathers are in relation to their partners.

In Garnett’s novella, Mrs Tebrick is not with child when she transforms, and her husband seeks to keep her as he always has. He brushes and perfumes her, plays her the piano, sits her upright fully clothed and plays card games with her. Only when her bloodlust becomes too great does he let her go and then she takes up with Renard and procreates. Her punishment for such wild impropriety is death.

In ‘Mrs Fox’, there is scant pretence at keeping the wife human. Her husband quickly realises she is all fox. He is seduced by her earthiness.

He puts his hand to her side, where she is reddest. The texture of her belly is smooth and delicate, like scar tissue, small nubbed teats under the fur. Her smell is gamey, smoky, sexual.

He provides a raw pigeon for her to eat. He surmises that her dramatic physical change is ‘an act of will’, as it is when pregnancy is sought. He is distanced from her by his lack of transformation. ‘She is in the house, a bright mass, a beautiful arch being, but he feels increasingly alone.’

Within days he lets nature claim her, worrying when she is gone about all the things that might befall her. He goes through her intimate possessions to feel close to her, he tries to masturbate but cannot without her; suggesting that physical presence is much more powerful than the imagination. He walks into the woods again and we are treated to lush poetic descriptions of natural forms, shivering stems and spermy blossom. It all serves the theme of parenthood as instinct. Though we ‘invest in bricks, in the concept of a home’, we are all animals in our base states, our intellectual capacities suddenly diminished by sex and birth, by illness and death.

Within days he lets nature claim her, worrying when she is gone about all the things that might befall her. He goes through her intimate possessions to feel close to her, he tries to masturbate but cannot without her; suggesting that physical presence is much more powerful than the imagination. He walks into the woods again and we are treated to lush poetic descriptions of natural forms, shivering stems and spermy blossom. It all serves the theme of parenthood as instinct. Though we ‘invest in bricks, in the concept of a home’, we are all animals in our base states, our intellectual capacities suddenly diminished by sex and birth, by illness and death.

Wound tightly in this story of instinctual states is the question of sexual difference. ‘And what of his wife? She is in part unknowable, as all clever women are.’ But is this not just the way ALL women are? In the same way that all men are unknowable to women? A man may be altered emotionally by parenthood, but he will never experience the fundamental physical transformation undergone by the woman.

When Sophia returns to her husband with her cubs, she is still a wild instinctive creature. Unlike Garnett’s narrator, her husband has not been cuckolded by another male but by his own offspring. He has been demoted. He is now an observer of the natural affinity Sophia shares with her cubs. He did not grow them squirming within him, nor did he feed them from his teats. At the end of the story, he fantasizes about his wife coming back to him, presumably when the cubs have matured. He hopes she will ‘walk through the garden naked, her hair long and tangled, her body glorified by use’, but he realises that it is the fox he longs for, that her loss ‘would be unendurable’. It is a very matriarchal message, one that brings to mind the rotund, big-boobed earth mothers of so many mythologies, the formidable strength of Gaia, the great mother of all.

There are many forms of parenthood, all as valid as the next, but ‘Mrs Fox’ spoke to me of the sheer visceral physicality of becoming a mother and the emotional turmoil it brings from the moment of conception to the moment we die. It made me remember how shocked I was by the act of giving birth and how when I mentioned this to my mother she said, ‘that was the easy bit’. Like ‘Mrs Fox’, becoming a mother transforms you into something else.

One thought on “The Two Mrs Foxes”

Comments are closed.