photo by Mario Mancuso

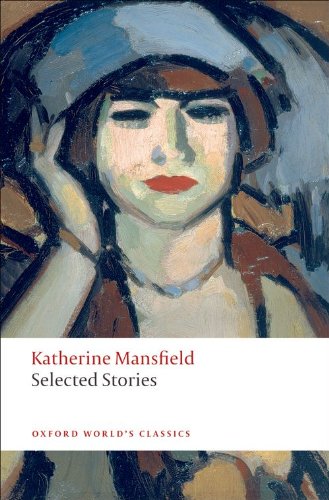

Gill Thompson rediscovers the stories of Katherine Mansfield, in an essay named as one of two runners-up in the 2014 THRESHOLDS International Short Fiction Feature Writing Competition. .

*

Comments from the judging panel:

‘I’d thought that there would be little more to say about Katherine Mansfield, but I was wrong’; ‘an engaging examination of Mansfield’s work and how the writer’s perception of the stories has changed since first reading them as a student’; ‘a rich exploration from the first word to the last’.

*

by Gill Thompson

When I first encountered Katherine Mansfield’s short stories, as an English Literature A-level student, I saw her writing as a kind of Lonely Planet Guide to the early twentieth century. I loved the landscape of garden parties, balls and upper class houses. The mannered speech and careful record of class distinctions were fascinating and even the New Zealand stories, though a strange departure from her European scenes, were interesting in their way. But I wasn’t sure whether any of the stories had a message for me beyond that.

Fast forward twenty years and, now an English teacher, I found myself having to prepare those same stories for my own class of sixth formers. I read them entirely differently. I realised that the aspects I had loved as an eighteen-year-old were only the props; the true human dramas lay beneath. I had missed them completely.

Claire Tomalin, in her introduction to the Everyman edition of Mansfield’s Short Stories, writes, ‘There was a Katherine Mansfield who was in love with little things – tiny children, small animals, pet names, frail old ladies, dolls’ houses.’ But Tomalin suggests this was a myth, carefully constructed after her death by Mansfield’s husband John Middleton Murry. ‘This exquisite person,’ Tomalin continues, ‘is at odds with the writer of many of her stories.’ If Mansfield was a miniaturist, she reserved her delicate touch for her writing. V. S Pritchett, writing in the New Statesman in 1946, praised her ability:

…her economy, the boldness of her comic gift, her speed, her dramatic changes of the point of interest, her power to dissolve and reassemble a character and situation by a few lines.

Mansfield knew, as short story writer Jayne Anne Phillips illustrates, ‘the form demands economy, precision and the attention to every word that is necessary in each line we write.’ And it is in these minutiae of detail, upon which the plot of a story often turns, that Mansfield’s skill lies.

Take ‘Bliss’ for instance. It was written in 1918, just as frantic hedonism was beginning its attempt to expunge the horrors of the First World War. Bertha, a young married woman, leads a seemingly perfect life. As she herself proclaims:

She had everything. She was young. Harry and she were as much in love as ever, and they got on together splendidly and were really good pals. She had an adorable baby. They didn’t have to worry about money. They had this absolutely satisfactory house and garden. And friends – modern, thrilling friends, writers and painters and poets or people keen on social questions – just the kind of friends they wanted. And then there were books, and there was music, and she had found a wonderful little dressmaker, and they were going abroad in the summer, and their new cook made the most superb omelettes…

A casual reader might be impressed by Bertha’s good fortune, but in Mansfield’s stories, little is as it seems. The discerning scholar would have noticed the warning implicit in an earlier line in the text, when Bertha exclaims, ‘I’m too happy – too happy!’ Here the intensifier ‘too’, a tiny word that precedes the long, self-congratulatory paragraph, is all that is needed to alert the reader to the hollowness behind Bertha’s apparent happiness. In fact, the husband who, she imagines, is so much in love with her, is having an affair. In addition, the ‘adorable baby’ belongs more to the nurse than its own mother, and Bertha has to watch them, ‘like the poor little girl in front of the rich girl with the doll’. Bertha Young’s bliss is built on falsehood and it is Mansfield’s careful placing of one word that points us to this.

A casual reader might be impressed by Bertha’s good fortune, but in Mansfield’s stories, little is as it seems. The discerning scholar would have noticed the warning implicit in an earlier line in the text, when Bertha exclaims, ‘I’m too happy – too happy!’ Here the intensifier ‘too’, a tiny word that precedes the long, self-congratulatory paragraph, is all that is needed to alert the reader to the hollowness behind Bertha’s apparent happiness. In fact, the husband who, she imagines, is so much in love with her, is having an affair. In addition, the ‘adorable baby’ belongs more to the nurse than its own mother, and Bertha has to watch them, ‘like the poor little girl in front of the rich girl with the doll’. Bertha Young’s bliss is built on falsehood and it is Mansfield’s careful placing of one word that points us to this.

She does this in many of her stories. In ‘The Tiredness of Rosabel’ the word is ‘optimism’. It doesn’t come until the very end when Mansfield writes of a young shop girl’s ‘tragic optimism, which is all too often the inheritance of youth’. Rosabel, the girl in question, spends her days selling beautiful hats to spoiled women, such as a recent customer whose suitor treats her with the deference due her social status whilst leering at working class Rosabel. But Rosabel is unaware of the insult. She lives in a dream world, preferring to buy herself violets rather than a hot meal, and regarding dull jewelers’ shops as fairy palaces when seen through the illuminated windows of a grimy London bus. Mansfield paints Rosabel’s poverty through descriptions of the ‘grey light’ of her room and the ‘coarse, calico night dress’ she wears, but the real sadness of the story lies in the misplaced hopefulness of her fantasies. ‘Tragic optimism’ says it all.

The very best short story writers, and Katherine Mansfield is clearly one of these, can distill a profound theme into a word or phrase. Within her short story collections she encapsulates youthful naivety, sexual ambivalence, male dominance and female complicity in succinct and deft lexis.

Sometimes this is done with humour, as in ‘A Birthday’. Although up all night with birth pains, poor expectant mother Anna Binzer still sends her mother to enquire after her husband’s cold and to advise him to don a warm vest. At this reminder of his indisposition, the hypochondriac Andreas immediately starts coughing to test out the health of his throat, completely oblivious to his wife’s agony. He undergoes the horror of a long wait for the child to be born, in which he tortures himself trying to anticipate its gender, and then becomes convinced his wife has died. Although Mansfield proclaims Andreas’ delight when he finds he has a son and informs us that Anna is, in fact, fine, she reserves her gentle mockery for the ironic reference to the husband’s ‘suffering’ in the last line. Another mot juste.

A further thematic distillation, albeit a far more ominous one, occurs in ‘Frau Brechenmacher Attends a Wedding’, when masculine brutality is conveyed through the menacing verb ‘lurched’ to describe a drunken husband’s entry into his fearful wife’s bedroom. In ‘The Daughters of the Late Colonel’, an uppity servant is characterised by the soubriquet ‘princess’ (little else is needed) and a snobbish nurse by her exaggerated pronunciation of ‘buttah’.

Sometimes Mansfield invites us to supply a key word ourselves. In her 1921 story ‘The Garden Party’, young Laura Sheridan is at first enchanted by her mother’s determination to host the ideal occasion. Laura is thrilled by the fact that ‘hundreds, yes literally hundreds’ of roses had come out overnight and she delights in the clothes, the marquee and the food, the highlight of which are the cream puffs – perhaps symbolising the insubstantial nature of the Sheridans’ concerns. But, suddenly, the perfect day is spoiled by the news that one of the workmen in the village has been killed. Mrs Sheridan insists the party must go on, but afterwards Laura takes a basket of leftovers, including the famous cream puffs, to the dead man’s family. Much to her horror, his widow invites Laura in to see the body. Afterwards, overwhelmed by her first encounter with death, Laura tries to convey the experience to her brother. But all she can say is: ‘Isn’t life____.’ We must guess at the omission, as Laura’s brother only replies, ‘Isn’t it, darling?’ Mansfield’s immaculate precision with language leaves room for our own interpretation.

Sometimes Mansfield invites us to supply a key word ourselves. In her 1921 story ‘The Garden Party’, young Laura Sheridan is at first enchanted by her mother’s determination to host the ideal occasion. Laura is thrilled by the fact that ‘hundreds, yes literally hundreds’ of roses had come out overnight and she delights in the clothes, the marquee and the food, the highlight of which are the cream puffs – perhaps symbolising the insubstantial nature of the Sheridans’ concerns. But, suddenly, the perfect day is spoiled by the news that one of the workmen in the village has been killed. Mrs Sheridan insists the party must go on, but afterwards Laura takes a basket of leftovers, including the famous cream puffs, to the dead man’s family. Much to her horror, his widow invites Laura in to see the body. Afterwards, overwhelmed by her first encounter with death, Laura tries to convey the experience to her brother. But all she can say is: ‘Isn’t life____.’ We must guess at the omission, as Laura’s brother only replies, ‘Isn’t it, darling?’ Mansfield’s immaculate precision with language leaves room for our own interpretation.

In a letter to Sylvia Payne in 1906, Mansfield wrote:

Would you not like to try all sorts of lives – one is so very small – but that is the satisfaction of writing – one can impersonate so many people.

Maybe Mansfield’s deft characterisation did elevate her stature; it certainly contributed to her far-reaching legacy. But ironically her lament, ‘one is so very small’, may highlight her strongest asset.

Last year, Auckland sculptor Virginia King created a model of Mansfield to be displayed in Wellington, New Zealand, Mansfield’s birthplace. The statue was titled ‘Woman of Words’ and covered with words from her stories. I bet every one was perfect.

~

Gill Thompson teaches A Level English at a sixth form college in Hampshire. She is studying for an M.A in Creative Writing at the University of Chichester and is halfway through writing her first novel, White Stock, about a child migrant to Australia.

Gill Thompson teaches A Level English at a sixth form college in Hampshire. She is studying for an M.A in Creative Writing at the University of Chichester and is halfway through writing her first novel, White Stock, about a child migrant to Australia.