photo by Alessandro Grussu

by Louise Hegarty

‘The South’ by Jorge Luis Borges was first published in La Nación, in 1953, and subsequently featured in the second edition of his short story collection Ficciones. At first, ‘The South’ may not seem like a typical example of his work, but Borges himself, in the prologue to the collection, wrote that it was his best story.

It is a story about opposites: the hellish North versus the open skied South, reality versus the world of dreams, life versus death, German versus Argentine. In less than three thousand words, Borges deals with all of this and also introduces a strong autobiographical element.

The story starts with a brief, but detailed paragraph about Juan Dahlmann’s family history. His paternal grandfather came from Germany, arriving in Buenos Aires in 1871. His mother’s family, however, are Argentinian through and through. Though part German, Dahlmann feels ‘profoundly Argentinian’ and thinks of himself as a Romantic, in the vein of his Latin ancestors. His heritage is at the heart of what the South represents for him. It is home. It is his identity.

At the cost of numerous small privations, Dahlmann had managed to save the empty shell of a ranch in the South which had belonged to the Flores family; he continually recalled the image of the balsamic eucalyptus trees and the great rose-colored house which had once been crimson. His duties, perhaps even indolence, kept him in the city.

At the cost of numerous small privations, Dahlmann had managed to save the empty shell of a ranch in the South which had belonged to the Flores family; he continually recalled the image of the balsamic eucalyptus trees and the great rose-colored house which had once been crimson. His duties, perhaps even indolence, kept him in the city.

Dahlmann relates his current identity to his past, rather than his present life in Buenos Aires. He is kept in the city because of his work, but sees both the city and the North very negatively in comparison to his idealised fantasy of the South, which he considers to be his spiritual home.

Dahlmann’s efforts to go south reflect his efforts to cling to his heritage, rejecting the North in the same way he rejects his ‘cold’ German roots in favour of his Romantic Argentinian background. However, things are not as easy as all that. When Dahlmann returns to the South after a stay in a sanatorium, he finds himself to be very much an outsider:

The country was vast but at the same time intimate and, in some measure, secret. The limitless country sometimes contained only a solitary bull. The solitude was perfect, perhaps hostile, and it might have occurred to Dahlmann that he was travelling into the past and not merely south.

If we take ‘The South’ at face value, the narrative is simply the story of a man who recovers from an illness, travels to his family’s homeland and dies in a glorious knife fight. But, the story is not as straightforward as it may seem. Borges stated, “Of ‘The South’, which is perhaps my best story, let it suffice that it can be read as a direct narrative of novelistic events, and also in another way.” It is possible to read the story as Dahlmann attempting to escape his inevitable death in the Northern hospital, by allowing his mind to travel south and imagine an exhilarating end for himself. An idealised death in the place where he thinks he belongs, rather than the reality of dying alone in hospital.

Death clings to this story from the very start. Twice Dahlmann feels something brush by his face; a portent of death, perhaps. He first feels this ‘brush with death’ when he cuts his forehead, and secondly just before he enters the knife fight.

As he crossed the threshold, he felt that to die in a knife fight, under the open sky, and going forward to the attack, would have been a liberation, a joy, and a festive occasion, on the first night in the sanitarium, when they stuck him with the needle. He felt that if he had been able to choose, then, or to dream his death, this would have been the death he would have chosen or dreamt.

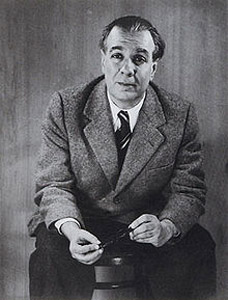

The story is heavy with illness and death, so much so that it is difficult to tell when life ends and death begins. The way Borges deals with illness and Dahlmann’s stay in the sanitorium is very interesting, as Borges is speaking from experience; he suffered a head wound in 1939 and almost died of blood poisoning. Here, he separates the facts of disease from the experience of illness itself.

The story is heavy with illness and death, so much so that it is difficult to tell when life ends and death begins. The way Borges deals with illness and Dahlmann’s stay in the sanitorium is very interesting, as Borges is speaking from experience; he suffered a head wound in 1939 and almost died of blood poisoning. Here, he separates the facts of disease from the experience of illness itself.

When he arrived at his destination, they undressed him, shaved his head, bound him with metal fastenings to a stretcher; they shone bright lights on him until he was blind and dizzy, auscultated him, and a masked man stuck a needle into his arm. He awoke with a feeling of nausea, covered with a bandage, in a cell with something of a well about it; in the days and nights which followed the operation he came to realize that he had merely been, up until then, in a suburb of hell.

This is a story about Argentina, about home, identity, fantasy, dreams, death, and immigration. Only Borges could contain all of this in less than three thousand words. This is what I love about Borges as a writer, and ‘The South’ in particular. It is a short story that can be understood in different ways. It requires numerous readings to break open the knotted plotlines, but with every read something else is revealed. ‘The South’ is most definitely vintage Borges.