photo by dixieroadrash

by Mary Larsen

Holly Goddard Jones, a relatively new Southern writer, may not have the experience that decades of short story writing brings, but she’s easily as skilled as the likes of Raymond Carver and Alice Munroe. Particularly when it comes to depicting the dynamics of family relationships and the hardships we face out in the cruel world.

The stories in Jones’ first collection, Girl Trouble, accurately capture the emotional responses and struggles we all face within relationships. She takes horrendous incidents – involving crimes, rape and violence – and then focuses in on the internal worlds of her characters. The inner struggle she so effectively creates, as her characters attempt to overcome their pain, allows the reader to feel an overwhelming sense of empathy, and to become devoted to the outcome of each story.

In ‘Retrospective’, it’s easy to get emotionally involved with the main character, Libby, who is raped by a teenager while home alone with her two young boys. The reader sees Libby’s marriage to Stephen falling apart; he has moved on from the incident, but Libby still lives with the horror, which Stephen couldn’t save her from. At the end of the story, Libby confronts Stephen and he is, ultimately, the one who is left desolate:

But her glimpse – and it couldn’t have been more than a flash in her mirror, and maybe she’d only imagined it, anyhow – was of Stephen on his knees, holding open her handbag, gathering its contents. His hands touching her things, the lipsticks and aspirin and other domestic notions.

Libby finally sees Stephen, quite literally, picking up pieces of their broken marriage, and realises that she no longer has to carry this heavy weight. As she drives away from him, the reader is given a real sense of hope for her life ahead, though we do not know what that will be.

Libby finally sees Stephen, quite literally, picking up pieces of their broken marriage, and realises that she no longer has to carry this heavy weight. As she drives away from him, the reader is given a real sense of hope for her life ahead, though we do not know what that will be.

This is an aspect of Jones’ storytelling that is most enjoyable throughout the collection. Her stories do not get wrapped up into neat little packages. In fact, they rarely end in a resolution of any kind and, most often, the characters are left in as much turmoil as when you first encounter them. But through this method, Jones makes the turmoil linger in her readers’ minds, long after the story is over.

Several stories have this lasting emotional effect, particularly ‘Parts’, which is narrated by the mother of a girl who has been raped and set on fire in her dorm room. Using simple terms, Jones translates a mother’s grief onto the page:

So many holes in that. So much to doubt. But I want to believe that Marty had told the truth because Felicia had deemed him good, or at least good enough to sleep with. I’ve spent the five years since Felicia’s death trying to reconcile the girl I knew, the daughter I’d made it my life’s business to love, with the secrets that reveal themselves in death. You either make allowances or you lose the person a second time, and that’s just the way of things.

This passage isn’t heavy-handed, it isn’t overtly clever or full of unnecessary detail, it simply takes us wholly into the mother’s heart. We are left to reflect on mortality, as the mother faces the possibility of losing her daughter a second time, through the secrets that have come out after her death.

The details Jones places in her stories all seem to be calculated to a particular purpose, and this reminds me of the great minimalist writers, such as Carver. She doesn’t give endless detail about setting or background, but instead seems to favour outlining only the parts that matter to her characters’ actions, often using ambiguity to infer violent undertones in her characters. In ‘Good Girl’, Jacob, the narrator, considers his wife and her relationship with their son, Tommy:

She missed the work. Tommy was late for a first child – Nora had miscarried four times before his birth, and she was thirty-eight when she delivered him – so she had adjusted to motherhood with difficulty as well as joy. When he was crawling age, she started making trips to the home to visit the residents, not worried like Jacob was about what germs the baby might pick up. The old people had loved touching the boy, planting dry, shaky kisses on his bald head. He never got sick, though. Not from them, not even a cold.

This passage tells a lot of information in a short space. We know that Nora misses her work, and we know that Jacob was more fretful about Tommy than she was. We can guess that Nora and Jacob probably won’t have any more children. The last sentence of this passage indicates an uneasiness around Tommy, even as a baby, by his unusual lack of sicknesses.

This passage tells a lot of information in a short space. We know that Nora misses her work, and we know that Jacob was more fretful about Tommy than she was. We can guess that Nora and Jacob probably won’t have any more children. The last sentence of this passage indicates an uneasiness around Tommy, even as a baby, by his unusual lack of sicknesses.

The story opens with Jacob receiving a visit from the town’s police chief, regarding Tommy’s dog – a female pit bull Tommy intended to train to be violent, until Jacob stepped in on ‘his son’s misguided whim’. However, the dog’s vicious nature has led her to attack a small girl, and Jacob must shoot the dog. Tommy’s aggressive tendencies towards the dog, and the visit from the police chief, foreshadow Tommy’s eventual arrest for the rape of a young girl, and Jacob’s final realisation of his son’s violent nature.

In an interview with The Kenyon Review, Nancy Zafris asks how Jones, as a young writer, is able to portray so much maturity and empathy through her characters. Her answer is quite simple, and humble: she attributes this sense of maturity to her marriage at the age of nineteen. Through this marriage, she feels as if she’s had some life experiences that allow her to relate to her older characters.

Jones may not have the wisdom that comes with age, but you wouldn’t know it. Instead, she elegantly shows that even a small town in Kentucky can have enough heartbreak and grief to write truly great stories. For me, her writing sits comfortably alongside the great short story writers and I am sure that she will be an author we’ll still be reading many years down the road.

~

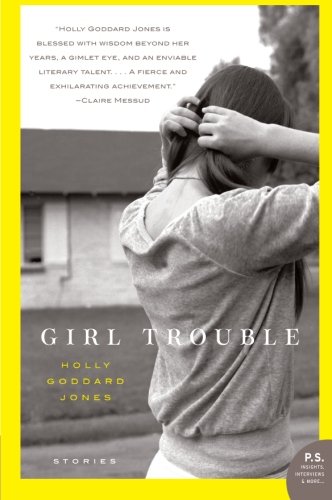

Image of Holly Goddard Jones © Morgan Marie Photography