photo by Ondra Anderle

by Erinna Mettler

“Bah!” said Scrooge, “Humbug!”

My favourite Christmas stories go easy on the sentiment. The actual nativity isn’t exactly all sunshine, is it? Mary and Joseph are too poor to rent a room, and then there’s those shepherds spending the night on the hillside. So instead of real-life Santas and sugar-plum happy endings, just one story has become traditional in my house. When the shopping days dwindle and the nights draw in, I always find the time to settle down in an armchair and read ‘Auggie Wren’s Christmas Story‘ by Paul Auster.

I’m a big Paul Auster fan. Have been since I discovered the intellectualised pulp of The New York Trilogy back in the 1980s. I think he has a certain irresistible melancholy, a way of looking at the world that sums up the connections we have to everyone else, all those little coincidences that seem  to make life more bearable. I also like the fluctuation of emotion in his stories; one minute amused, then puzzled, then sobbing uncontrollably. And then there’s the beautifully sparse yet poetic prose.

to make life more bearable. I also like the fluctuation of emotion in his stories; one minute amused, then puzzled, then sobbing uncontrollably. And then there’s the beautifully sparse yet poetic prose.

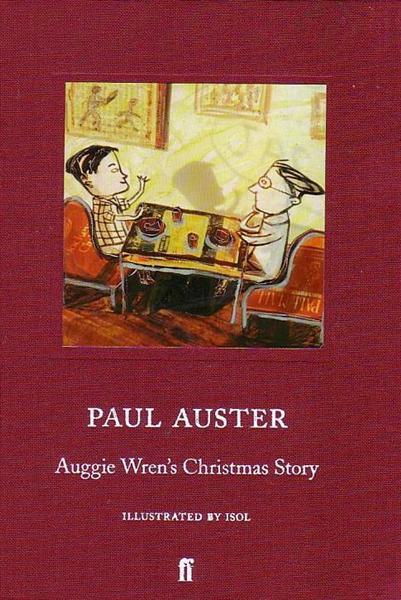

My husband bought me a copy of the illustrated edition of ‘Auggie Wren’s Christmas Story’ a couple of years ago. The black and white, full-page illustrations, by Argentinian artist Isol, somehow make you believe you are holding the story in your hands. It is one of my all-time favourite Christmas presents, and that’s before I’ve even started on the story. Initially written for the Christmas Day edition of The New York Times in 1990 (then used as a plot in the 1995 film Smoke), Auster has always maintained that he set out to write an unsentimental Christmas story (or, on reflection, perhaps that is just the character ‘Paul’ in the story). I’m not sure he succeeded, though. There is a gritty quality, a sharp element of loneliness and desperation running throughout, but the story is sentimental too, heart-warming even, and it leaves a festive glow. For me, it is this combination of hope and realism that makes it a classic. After all, isn’t this what Dickens’ ‘A Christmas Carol‘ and Philip Van Doren Stern’s ‘The Greatest Gift‘ (the inspiration behind It’s a Wonderful Life) were all about? Even in the depths of despair and loneliness there’s always room for a little human kindness.

The story concerns a ‘fictional’ author named Paul trying to fulfil a commission to write a Christmas story for The New York Times. He is well and truly blocked, afraid of succumbing to festive saccharin. He explains his predicament to Auggie Wren, the owner of a cigar store he frequents. We flashback to the time Paul got to know Auggie by way of the cigar pedlar’s hobby. Auggie takes a photograph every day from the same spot outside his cigar store. The results are described thus:

Auggie was photographing time, I realized, both natural time and human time, and he was doing it by planting himself in one tiny corner of the world and willing it to be his own.

In the context of the story, Auggie’s photographs show us the connection of the individual to the bigger picture, as the seasons change and regulars mingle with unknown faces, ‘living an instant of their lives in the field of Auggie’s camera’.

It continues:

Once I got to know them, I began to study their postures, the way they carried themselves from one morning to the next, trying to discover their moods from these surface indications, as if I could imagine stories for them, as if I could penetrate the invisible dramas locked into their bodies.

Auggie himself offers such a story – ‘the best Christmas story you ever heard’ – in exchange for lunch. In the opening paragraph of the book, Auster sums up what is going to happen in Auggie’s story:

I heard this story from Auggie Wren. Since Auggie doesn’t come off too well in it, at least not as well as he’d like to, he’s asked me not to use his real name. Other than that, the whole business about the lost wallet and the blind woman and the Christmas dinner is just as he told me.

It’s an audacious way to start a story, to pre-empt your tale in the first few sentences, giving away the main elements of the plot. But I think the way the opening is written makes it impossible for you not to read on. You know so much from it, and yet not nearly enough. You know that Auggie doesn’t like the way he comes across, that there is some flaw in his behaviour. From the outset you know that the story isn’t all candles and mistletoe, but you also have the potentially sentimental elements of a lost wallet, a blind woman and a shared Christmas dinner. Already you are guessing what will happen; you are participating in the invention of a Christmas tale.

It’s an audacious way to start a story, to pre-empt your tale in the first few sentences, giving away the main elements of the plot. But I think the way the opening is written makes it impossible for you not to read on. You know so much from it, and yet not nearly enough. You know that Auggie doesn’t like the way he comes across, that there is some flaw in his behaviour. From the outset you know that the story isn’t all candles and mistletoe, but you also have the potentially sentimental elements of a lost wallet, a blind woman and a shared Christmas dinner. Already you are guessing what will happen; you are participating in the invention of a Christmas tale.

This is my favourite type of story, one in which the reader plays as big a part as the author in the creation of the narrative. At the end of Auster’s story we (and the character Paul) are left wondering if Auggie hasn’t made the whole thing up to dupe his friend out of a free lunch. The reader is left to decide: is it true, or invented, or both? Is Auggie a nice guy or not? Does it matter, so long as the story offers some insight into the human condition, a desire to spread good will amongst our neighbours, a little hope for the Christmas season? As Auster says in answer to the questions raised by his Christmas tale: ‘As long as there’s one person to believe it, there’s no story that can’t be true.’

One thought on “In Praise of Auggie Wren”

Comments are closed.