by Will Bowerman

Haruki Murakami was born in Kyoto in 1949. His parents taught Japanese Language and Literature and he was instilled with a voracious appetite for books from an early age. As he was an only child, Murakami’s parents were strict, but allowed him freedom to go hiking and explore his environment. He was permitted to buy books on credit at the local bookstore, so long as they never included magazines or comics. He began to write for his school paper and fell in love with American detective novels and Western pop culture in an emerging world of post-war occupation.

Murakami studied Literature at Waseda University in Tokyo, where he was to meet his wife. The new couple took out a loan to open a jazz club in Tokyo, ‘Peter Cat’, when Murakami was just 25. Four years later, he decided to write his first novel – Hear the Wind Sing – after attending a baseball game. The novel won ‘Gunzo’ Magazine’s Newcomer’s Award for 1979. Murakami quickly followed up this success with a second novel – Pinball, 1973 – and short stories. Both Hear the Wind Sing and Pinball, 1973 were nominated for the Akutagawa Prize. Though neither book won, they solidified his reputation as a fresh and emerging literary talent. Encouraged by this success, Murakami closed the jazz club so that he could write full time. His next novel, A Wild Sheep Chase (1982), disappointed his publishers for its fantastical characters, but attracted a solid readership and won the prestigious Noma Literary Newcomer’s Prize. Murakami could now afford to devote himself to a literary career.

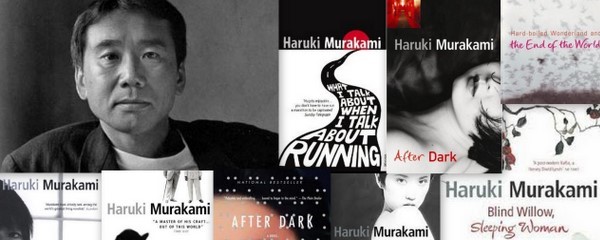

Hard Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World (1985) followed and proved a masterful novel of perception, dreams and the parallel worlds of the fantastic and the real. This was the first occasion for Murakami in which a novel was composed from a short story. Dissatisfied with the original, the short story was to provide the catalyst for expansion and development into what would become Murakami’s first novel written with a pre-conceived structure in place. This novel won the Tanizaki Prize.

Another short story was to provide Murakami with the inspiration for his next novel, Norwegian Wood (1987). The amazing success of this novel (selling over three and a half million copies in Japan in just over a year) pushed the intensely private Murakami into the realms of best selling author and national icon, and caused him to flee his homeland to live in Europe. Later, he moved to the United States, where he taught at Princeton University, and it was during this time that Murakami was finally able to arrange a personal meeting with Raymond Carver, whose work he had translated into Japanese. The Murakamis were not to return to Japan to live for three years.

Preferring to alternate between writing novels and short fiction, Murakami began writing short stories again, and published a collection which was translated into English as The Elephant Vanishes (1993). The novels The Wind-up Bird Chronicle (1994-5) and Sputnik Sweetheart (1999) were also composed from previously published short stories. After the Quake (2000), a collection of short fiction loosely based around the 1995 Kobe earthquake, was to fall between Sputnik Sweetheart (1999) and Kafka on the Shore (2002). A keen marathon runner, Murakami equates novel writing to running marathons and short story writing to sprinting. There exists omission within short stories, but what is included is essential to achieving its purpose.

He has continued to write novels, short stories, travel writing, essays and non fiction, and has translated the works of American writers such as Raymond Carver, John Updike, Truman Capote, Tim O’Brien, J.D. Salinger and F. Scott Fitzgerald into Japanese. His novels continue to win literary prizes, enhancing his reputation, while he himself refuses to take part in television interviews or appear in public with any regularity. Murakami was awarded the Jerusalem Prize in 2009 and his name appears each year amongst the contenders for the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Murakami’s style is infused with a conscious effort to adhere to spareness, rhythm and humour. References to music flow through all of his works, and there is a measurable rise in jazz, pop and classical music sales whenever they are mentioned in one of his novels. Dreams, baseball, imperfect characters, other worlds, passive characters thrown into fantastical quests, talking animals, and unexplained events conspire in themes of love, connection, alienation and Japanese identity. No two works are alike and their subjects cannot be predicted before release. Murakami readers, even obsessive followers, await each new work as an act of discovery, but answers will not always be forthcoming to those with questions. His novels require the reader to take a leap of faith and those who do are richly rewarded.

Each release is met with breathless anticipation, as illustrated in Japan last year on the unveiling of Murakami’s new novel IQ84 Volumes 1 and 2, when over two million copies were printed to satisfy early demand. Volume 3 has recently been released in Japan with an initial print run of 700,000, completing the mammoth trilogy of over 1600 pages.

Aside from this expansive work, Murakami believes that short stories can be created out of the smallest of details. As he stated in his introduction to his most recent short story collection, Blind Willow, Sleeping Woman (2006), ‘short stories are like guideposts to my heart, and it makes me happy as a writer to be able to share these intimate feelings with my readers.’