photo by Steve McNicholas

by Kirsty Walters

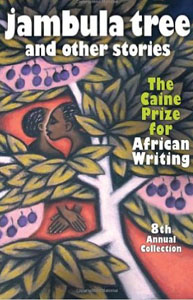

Never has a collection of short stories lit in me such a mixture of emotions. One moment I was close to tears and the next I was enraged. Jambula Tree and Other Stories is the 2007 anthology for the winner and shortlisted writers in the Caine Prize, along with stories written at the Caine Prize Writers Workshop.

My favourite story in the collection, ‘My Parents’ Bedroom’, comes from Nigerian writer Uwem Akpan. It describes the events of the 1994 genocide in Rwanda, through the eyes of a young girl of mixed heritage. At first, the reader is as unknowing as the girl, as whispering spreads throughout the empty house and a mob of neighbours and relatives gather outside. Alone with her younger brother, the protagonist is at the mercy of the machete-wielding gang. Her uncle shouts and rages through the house, insinuating that her father owes him money, and the young girl keeps out of his way:

Tonton Andre is bitter and restless. Since I told him that my parents have gone out, he hasn’t spoken a word to me. I’m angry at him, too, because he lied to get in and now the Wizard has destroyed my crucifix and stolen Christ’s body.

Seeing the events through the eyes of this young, religious girl gives the story an almost mystical feeling. But when her father is forced to kill her mother, due to her Tutsi heritage, whilst the children watch on, the situation feels all too real and utterly devastating. The story ends with the two children slipping away through the bush whilst their house is burnt down and a war rages on around them.

Another story that touches on the unrest in Africa is ‘The Lost Boy’ by Kenyan Kaume Marambii. It begins:

I am Africa…Dreaming. When at last I sleep, I dream…beautiful dreams, fantastical dreams. I am the king of the universe. I laugh as I run, the wind in my face. My sandaled feet kick up little swirling dust devils from the dry grass. I am young and strong and I run lightly, untiring. My smooth long-limbed strides eat up the distance. My second wind kicks in and I breathe easily, steadily. At this pace I can run forever.

A strange beginning to a short story, but Marambii’s opening and closing paragraphs are near identical. They frame the main story, making the meaning and impact of this opening clear.

A strange beginning to a short story, but Marambii’s opening and closing paragraphs are near identical. They frame the main story, making the meaning and impact of this opening clear.

The story switches between three protagonists: a man about to be executed, the man doing the executing, and his wife waiting at home. All three are joined together by this ghastly incident. However, we don’t fully understand the events that have led up to this execution until the end of the story, where we are made to feel surprising sympathy for the executioner. Marambii forces the reader to question how these people have reached this point, and we realise that everyone has a story to tell, if we are only willing to listen.

‘Night Bus’, by Nigerian writer Ada Udechukwu, tells the story of woman and her lover on a bus that is attacked by highway bandits. The story has a slower pace than some of the others in the collection, but the ending is powerful and shocking to the core; the girl’s lover is one of the bandits and he takes part in her gang rape. This is another story to make you stop and question humanity. Although ‘Night Bus’ is only a story, it reflects the dangers some people face on a daily basis and inevitably calls to mind all-too-real news reports.

Not only is this collection a commentary on humanity, but it’s also full of energetic and rich language. In ‘First Time’ by Kgaogelo Lekota, from South Africa, the narrator is caught up in a tricky situation and his language and thoughts almost seem to take on a mind of their own:

I was listening to the conversation but I switched off and drifted, it felt like sinking. It ponged pungently but I was drawn to it. Flying, drifting, dawdling, crawling, hiding, imbibing. It was salt. I brawled. Deliberated. Impregnated my thoughts like an expired inspired dream-catcher. I felt fancy but dirty. Clint Eastwood, gun at my hip; the fast, the deadly and the definitely dangerous.

Another writer with a talent for description is the winner of the competition, Monica Arac de Nyeko from Uganda. Her descriptions of life and people in the title story, ‘Jambula Tree’, are surprisingly original, perceptive and humorous:

Another writer with a talent for description is the winner of the competition, Monica Arac de Nyeko from Uganda. Her descriptions of life and people in the title story, ‘Jambula Tree’, are surprisingly original, perceptive and humorous:

Maman Akin cooks her kilo of offal, which she talks about for one week until the next time she cooks the next kilo again, bending over her charcoal stove, her large and long breasts watching over her saucepan like cow udders in space.

Though it is a serious story of two young girls, caught having an affair in Kenya and being forced to live forever in shame, there are plenty of these descriptive treats, too good to be missed.

A rather different and more mystical addition to the collection is ‘Jimmy Carter’s Eyes’, by Nigerian writer E. C. Osondu. A young girl loses her eyesight after a boiling pan falls on her. The rest of the village, of course, rally around the girl and her mother, offering well needed support. But as the months drag on, and the girl is still in hospital, the neighbours’ attentiveness wanes. When the girl finally returns to the village, the people are forced to reassess her place amongst them; the loss of her eyesight has given her the perception of the third eye. Soon, she has a steady flow of visitors requesting answers to endless questions, such as, “Will there be plenty of rain this year so I can plant cassava instead of yaga?” and “My black sheep did not come home with the rest of my sheep last night. Where could it be?” The girl answers all and the village begins to prosper. But when the girl is given the opportunity to have her eyesight restored, the people of the village are in uproar. More like a precious object belonging to the village than a living, breathing person, the girl is denied her eyesight. Osondu convincingly shows the power of mysticism and belief, and the way they can destroy or restore an individual’s life.

On the same theme of the lengths people will go for their beliefs is ‘For Honour’ by Stanley Onjezani Kenani from Malawi. This story tells of an infertile couple who use a fisi (a stand-in fertile mate) to become pregnant. It shows the husband’s struggle with knowing that another man is sleeping with his wife on a weekly basis. Although the infidelity sickens and angers him, to live without child is considered failure in their community and he is referred to as a chumba (a barren person). Just like many of the stories in the collection, this one does not have a happy ending, but is an interesting insight into the couple’s culture.

The stories in Jambula Tree are all at once educational, inspirational and beautifully written, with moving prose that is inspiring. It may not be the best collection to read if you’re in low spirits. But it’s definitely a collection that will broaden your perception of the world.