photo by Paul Sandham

by Lela Tredwell

You could say I know a thing or two about boxes. I once worked in a box factory and knew, first-hand, the frustrations of boxes that were too big, too small, too flimsy and too unyielding.

It therefore came as a surprise to discover that Robert Shearman likes little boxes. With his imagination, I thought he’d be into the ones used for washing machines, dishwashers and wardrobes. Think… that industrial-looking box in the opening scenes of Jurassic Park, which transports the ferocious specimen that sucks in the keeper.

Yet, whether cramming a heart into a tupperware box, a brood of winged rabbits into the boot of a car, or a dark space into a box into a house into a garden at the centre of the world, Robert Shearman keeps offering readers ‘big’ stories in deceptively small boxes.

For many, Robert Shearman is well known as the man who reintroduced the Dalek to our screens, in an episode of Doctor Who that was nominated for a Hugo Award. He has written for stage and radio, as well as screen – seven of his plays for stage can be found in print in Caustic Comedies. He’s also won a big box load of awards for these creations, amongst them The World Drama Trust Award and the Guinness/Royal National Theatre Award for Ingenuity. Like his short fiction, his plays often involve ordinary flawed people who are thrown into fantastic and bizarre situations. ‘Breaking Bread Together’, in which God lives in suburbia, attracted critical acclaim, as well as some unsurprising controversy. But Shearman hasn’t let that put him off; in his writing since, he’s shaken up the familiar figures of Jesus, Santa, the devil and even Hitler’s dog.

For many, Robert Shearman is well known as the man who reintroduced the Dalek to our screens, in an episode of Doctor Who that was nominated for a Hugo Award. He has written for stage and radio, as well as screen – seven of his plays for stage can be found in print in Caustic Comedies. He’s also won a big box load of awards for these creations, amongst them The World Drama Trust Award and the Guinness/Royal National Theatre Award for Ingenuity. Like his short fiction, his plays often involve ordinary flawed people who are thrown into fantastic and bizarre situations. ‘Breaking Bread Together’, in which God lives in suburbia, attracted critical acclaim, as well as some unsurprising controversy. But Shearman hasn’t let that put him off; in his writing since, he’s shaken up the familiar figures of Jesus, Santa, the devil and even Hitler’s dog.

In an interview with short story writer Angela Slatter, Shearman reflects on his experience of writing for theatre as having taught him not to be boring in his prose: ‘You begin to learn there’s a real responsibility to writing, and the greatest one is not to be dull’.

While in his twenties, Shearman’s mentor was the great British playwright Alan Ayckbourn, who regularly commissioned and directed Shearman’s work, taught him that ‘you could say anything in theatre, and do anything, as long as you gave the audience a reason to come back after the interval’. Shearman says he feels this is true for prose too: ‘Just give them a reason to move on to the next paragraph’.

Shearman’s short stories are often dark and mostly rather devious. He thrills his readers by exploring a whole host of surreal or absurd situations. It’s a kind of literary daring made possible, in his case, by an unfettered sense of humour. His first collection, Tiny Deaths, was published by Comma Press in 2007 and included the brilliant ‘So Proud’, an oddly charming story about a woman who gives birth to expensive furniture. The collection won the World Fantasy Award for Best Collection, was shortlisted for the Edge Hill Short Story Prize and was nominated for the Frank O’Connor International Short Story Prize. It was an impressive debut into short fiction, and Shearman was just getting started.

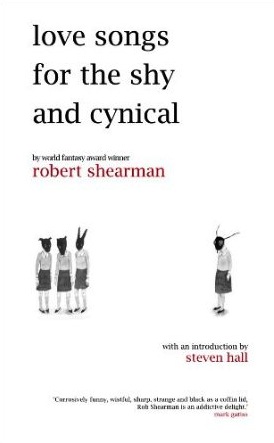

His second collection, published in 2009 by Big Finish, Love Songs for the Shy and Cynical, features stories that see a man taking a job as a tree, the Devil as a romantic fiction author, the disappearance of Luxembourg, and, in ‘Sweet Nothings’, the lovesick pain of a pig in the Garden of Eden:

For a few days the pig continued to compose his music. But it wasn’t very good; there comes a point when songs about heartbreak, no matter how earnest, are no longer artistic but merely petulant.

Though Shearman’s ‘love songs’ are about heartbreak, they are not like the peevish pig’s music – instead, they evoke a tenderness and lyricism as powerful as love itself. Love Songs for the Shy and Cynical won the British Fantasy Award for Best Collection, the Edge Hill Short Story Readers’ Prize and the Shirley Jackson Award, celebrating ‘outstanding achievement in the literature of psychological suspense, horror, and the dark fantastic’.

Though Shearman’s ‘love songs’ are about heartbreak, they are not like the peevish pig’s music – instead, they evoke a tenderness and lyricism as powerful as love itself. Love Songs for the Shy and Cynical won the British Fantasy Award for Best Collection, the Edge Hill Short Story Readers’ Prize and the Shirley Jackson Award, celebrating ‘outstanding achievement in the literature of psychological suspense, horror, and the dark fantastic’.

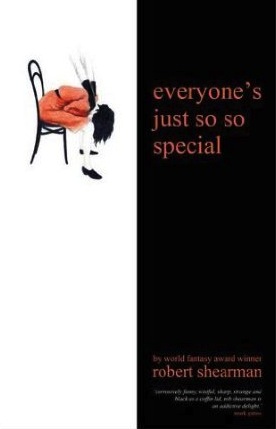

His third collection, Everyone’s Just So So Special, is home to what has to be one of my favourite Shearman stories, not least because it features a giant panda’s head manipulated into the box made for the shipping of a microwave. In the tale ‘Endangered Species’, a cat starts bringing home exotic animals as gifts while a hollowed out rhinoceros proves a step too far for the neighbours. The cat’s fantastical activities are expertly juxtaposed with the experience of a couple who are grieving for the loss of their baby son.

And the baby was screaming, and my wife was screaming – and yes downstairs I heard another join the chorus; the cat, the cat was screaming too. This was no ordinary ‘meep’ – this was a ‘meep’ with electrodes stuck into it, this was at full throttle, a war cry, a call to arms.

Many of Shearman’s stories deal with issues concerning parenthood, or a lack of it: lost children, lost parents, children losing parents, parents losing children. In perhaps one of his most disturbing stories, concerning a psychopathic ‘soup-spattered’  Santa Claus, a son loses his father in a gut-wrenching fashion. This grisly tale, entitled ‘Cold Snap’, appears in Shearman’s third collection and also in a retrospective of his dark fiction – Remember Why You Fear Me – which was produced by Chizine Publications last year. Accompanying the darkest of stories from his first three collections are ten new tales.

Santa Claus, a son loses his father in a gut-wrenching fashion. This grisly tale, entitled ‘Cold Snap’, appears in Shearman’s third collection and also in a retrospective of his dark fiction – Remember Why You Fear Me – which was produced by Chizine Publications last year. Accompanying the darkest of stories from his first three collections are ten new tales.

‘The Dark Space in the House in the House in the Garden at the Centre of the World’ is just one of these wonderful new stories, and can also be found in The Best British Short Stories 2012. This time, God is the sports jacket-wearing father of Cindy and Steve. He attempts to advise his offspring as to the best course of action; however, his children seem set on disregarding his recommendations and leave God’s garden in search of ghosts.

You can also find Shearman in The Best British Short Stories 2013. Just don’t read ‘Bedtime Stories for Yasmin’ late at night and expect to sleep afterwards.

And at the doorway she saw the darkness harden, and grow denser, and turn into the shape of a person, and she thought her heart would pop – and she thought, this is how my little daughter will find me in the morning, slumped dead against the pillows, my eyes open so wide in fear, oh, Yasmin.

Yasmin?

“Is that you, Yasmin?” she made herself ask.

And the figure said, quietly, “Yes.”

Like Yasmin, Shearman won’t be put to bed easily. The stories keep coming – rattling their cages, reaching out through the bars and dragging us in. Since 2011, Shearman has been supplying the digital realm of justsosospecial.com with short fiction – with the aim of reaching the total of One Hundred Stories. Each tale takes, as its inspiration, the name of a person special enough to have bought a limited edition copy of Everyone’s Just So So Special. Shearman reflects upon it now as “a very silly idea, born out of stupidity and arrogance” and yet still he writes on… and we remain so, so lucky that he does.

Shearman’s sense of mischief – in upending the world as we know it – inspires me in my own writing to play more and to risk more. Like that dinosaur in Jurassic Park, not even an industrial storage container could lock away the big imagination of Robert Shearman.

One thought on “The Deceptively Small Boxes of Robert Shearman”

Comments are closed.