photo by beanpumpkin

by Ever Dundas

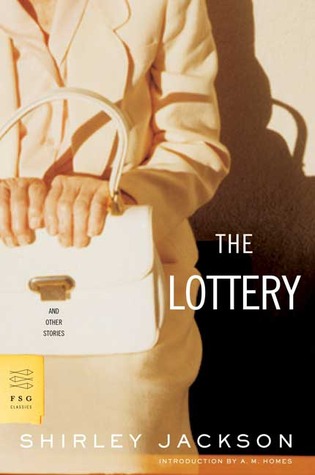

Shirley Jackson is famous for ‘The Lottery’, a short story that, at the time of publication in 1948, was tellingly controversial. It’s a powerful piece about the dangers of conformity, and contemporary descendants include The Running Man, Battle Royale, and The Hunger Games. ‘The Lottery’ and ‘The Witch’ can be considered companion pieces, approaching the same subject in a very different way. However, ‘The Witch’ is more subtle and difficult, and is my favourite Jackson short story.

The story begins with a mother on a train with her young son and baby girl. The son, Johnny, entertains himself by telling stories. “I saw a witch. There was a big old ugly old bad old witch outside,” he says to his mother. But she doesn’t encourage his flights of fancy. She is immured in the ordinary, and won’t shift her way of thinking, even to engage the boy’s imagination.

A stranger joins them in the carriage, a seemingly innocuous elderly man with ‘a pleasant face under white hair’. There is a genial exchange between Johnny and the man, as he asks the boy what he’s been looking at out of the train window. “Bad old mean witches,” replies the boy.

When asked how old he is, Johnny says “Twenty-six. Eight hundred and forty-eight.” The mother interrupts with Johnny’s real age, but the man ignores her and encourages Johnny’s make-believe: “Is that so? Twenty-six.” The man asks the boy’s name. “Mr Jesus,” he responds, getting a frown from his mother and an emphatic “Johnny.”

When asked how old he is, Johnny says “Twenty-six. Eight hundred and forty-eight.” The mother interrupts with Johnny’s real age, but the man ignores her and encourages Johnny’s make-believe: “Is that so? Twenty-six.” The man asks the boy’s name. “Mr Jesus,” he responds, getting a frown from his mother and an emphatic “Johnny.”

The mother, who was initially anxious when the stranger sat next to Johnny, returns to her reading. Conspiratorially, the man says to Johnny: “Shall I tell you about my little sister?”

“Was she a witch?” Johnny asks.

“Once upon a time…” the man begins, and he tells of his sister, who was just like Johnny’s baby sister; she was pretty and nice and he loved her. Johnny is captivated as the man says, “So shall I tell you what I did?”

He describes all the toys and sweets he bought her. The reader, like the mother, is smiling, nodding along with the old man’s story. Then, in an instant, this normal, ordinary scene escalates into something far more threatening: “I took her and I put my hands around her neck and I pinched her and I pinched her until she was dead.”

The reader is reeling from the punch of that line, just as the mother is shocked into silence, giving the old man time to continue: “And then I cut her head off…”

There is an understanding that this is make-believe, like Johnny’s witches; however sanitised they’ve become, fairytales are often full of violence and death. On the other hand, the shock factor leaves us wondering if this is more than a story; what will the man do? What is he capable of? Unease builds, as does the little boy’s curiosity and delight in gruesomeness. “Did you cut her all in pieces?” Johnny asks.

Jackson mirrors the reader’s shock and repulsion through the mother’s reaction. She finally gathers herself together and demands: “Just what do you think you’re doing? Get out of here.” When the stranger responds with “Did I frighten you?”, Jackson could well be directing this question at the reader. The man nudges Johnny, who laughs; they’re like a couple of young friends who are getting a kick from rattling a sensible adult.

In an attempt to gain control, the mother calls on the power of adult roles and authority: “I could very easily call the conductor.” Her threat isn’t dangerous like the man’s story, but, instead, highlights the power of words.

Johnny now sides with his mother, telling the man: “My mommy will eat you.” He is clearly playing and does not understand the potential threat the man has presented. But he is also acknowledging the power of his mother and the ‘proper’ adult world. In the same way she was dismissive of Johnny’s make-believe, the mother can dismiss the man too; she will devour him, neutralising the threat, enveloping him into her norms and sense of order. She ejects the stranger from her safe world, and turns to her son: “You sit still and be a good boy. You may have another lollipop.”

One could interpret the stranger’s behaviour as representing the evils of humanity – someone whose prime concern is to corrupt the boy – but the character isn’t so much evil as disruptive. He’s a troublemaker, a devil, a trickster, a witch.

One could interpret the stranger’s behaviour as representing the evils of humanity – someone whose prime concern is to corrupt the boy – but the character isn’t so much evil as disruptive. He’s a troublemaker, a devil, a trickster, a witch.

The stranger sides with the little boy, forcing the mother out of her complacency. The stranger is an adult who is fully engaged with his imagination, taking away the censorship of the ‘proper’ adult world. Conventions are overturned.

‘The Witch’ exposes adult hypocrisy. It recognises children as human beings and not romanticised visions of innocence. Instead, the boy is simultaneously innocent and savage (also reflected in Jackson’s biographical book about her life with four children, aptly titled Life Among the Savages, a humorous look at the trials of parenthood).

The story is akin to a fairytale; an amoral trickster-like character disrupts the protagonist’s life, prompting a profound change. However, Jackson arrests the fairytale outcome – the mother sinks back into the security of the ordinary, and the boy simply goes back to daydreaming and sucking on a lollipop.

Writers are disruptors, and Jackson certainly so. Many of her stories are about lonely people who are out of kilter with traditional conventions. What do we think of when we hear the word ‘witch’? We think of someone dark and evil, someone to be feared. We think of witch trials, of ordinary communities turning on innocent people (often women). It is at this point we return to the parallel with ‘The Lottery’ – the potential evil here isn’t the old man. It’s us. The reader. The ordinary person in an ordinary community.

Jackson leaves us feeling unsettled. She imbues the ordinary with unease and dread, and punctures the security of a commonplace experience with violence, or, at least, the risk of violence. Her stories show us that danger isn’t elsewhere, it isn’t with the strangers and witches. It’s here, in the domestic, in the ordinary, in the people around us.