photo by David Jones

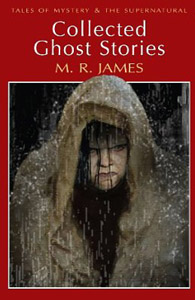

An exploration of M. R. James’

‘Oh Whistle, and I’ll Come To You, My Lad’

by Stephen Devereux

M. R. James’ ghost stories have had an enormous influence, not only on other writers, but on the treatment of the supernatural in film and other popular forms. He may not be widely read these days, but ‘Oh Whistle, and I’ll Come to You, My Lad’, first published in 1904, either introduced or refined many devices that are instantly recognisable elements of the supernatural now: an invisible ghost being made visible by covering it with a sheet; a window flying open in the wind, signalling the entrance of an evil spirit; ghosts or devils being inadvertently awoken through archaeology, or the discovery of an ancient manuscript.

At the heart of many of James’ stories are rational individuals who are at risk because they do not believe, and they must be saved by those who do. In modern horror, the supernatural is unambiguous, whereas James nearly always provides his readers with the possibility that there could be a rational explanation for inexplicable events.

‘Oh Whistle, and I’ll Come to You, My Lad’ begins with a group of academics at a Saint James’ College, Cambridge (there is no such college, but M. R. James was provost of King’s College – one of many ‘insider’ jokes in this and other tales). Parkins is a blunt, humourless rationalist whose subject is Ontography. (Another sly joke. There is no such subject, but it could be interpreted as the study of the meaning of everything on earth. Since James coined it, the word has entered the language). He is ribbed by his colleagues, particularly by a man called Rogers. He plans to go for a break to Burnstow on the Suffolk coast in order to improve his golf. He tells them that he is staying at the Globe Inn, in a room with two beds. Rogers offers to accompany him and make use of the second bed, but his offer is rudely declined. Another academic asks him to have a look at the remnants of a Templar preceptory on the coast near his hotel. With this apparently casual opening, James has put into place all the elements that will lead to the disturbing story that follows.

Several M. R. James stories are set on the Suffolk coast. I grew up there and have always found it to be the most eerie stretch of coast I know; its spooky atmosphere often creeps into my own poems and short stories. Nothing much happens to Parkins on his first day there. He plays golf with the Colonel who is at once a resilient, practical, fearless man, but also a believer in the supernatural – a Van Helsing or Indiana Jones figure. In the evening, Parkins goes to look for the site of the Templar church, tripping over a remnant of it hidden in the grass. The Knights Templar have long been associated with secret cults, buried treasure, torture, kidnap and conspiracies. Since James originally wrote his stories to read to his friends, students and colleagues, he could be certain that his audience were aware of the allusions and connections in his stories, such as those to the Knights Templar. Parkins soon finds a spot where the ‘turf was gone – removed by some boy or other creature ferae naturae’. This ought to raise his suspicions and make him wonder whether something hasn’t been planted there expressly for him to find – but by whom or by what? James frequently gives the reader little hints, possibilites, that evade his protagonists.

Sure enough, hidden in an enclosed space inside a small ruin, is an object. Parkins puts it in his pocket and turns to make his way back to the hotel in the twilight. He notices the ‘faint yellow light’, ‘the squat martello tower’, the ‘pale ribbon of sands intersected at intervals by black wooden groynes, the dim and murmuring sea’. For the first time in his rational, safe life, he is afraid. He has to climb over each of the groynes and keeps looking behind him. He sees an ‘indistinct personage, who seemed to be making great efforts to catch up with him, but made little, if any, progress. This is like the landscape of a nightmare sequence from a Hitchcock film. The logical ‘ontographer’ worries that if he looks back again, he might see ‘a black figure sharply defined against the yellow sky, and [see] that it had horns and wings’. James is no literary stylist, but the choice of diction, the brevity of the description, and the evocation of the landscape convey Parkins’ terror faultlessly.

Sure enough, hidden in an enclosed space inside a small ruin, is an object. Parkins puts it in his pocket and turns to make his way back to the hotel in the twilight. He notices the ‘faint yellow light’, ‘the squat martello tower’, the ‘pale ribbon of sands intersected at intervals by black wooden groynes, the dim and murmuring sea’. For the first time in his rational, safe life, he is afraid. He has to climb over each of the groynes and keeps looking behind him. He sees an ‘indistinct personage, who seemed to be making great efforts to catch up with him, but made little, if any, progress. This is like the landscape of a nightmare sequence from a Hitchcock film. The logical ‘ontographer’ worries that if he looks back again, he might see ‘a black figure sharply defined against the yellow sky, and [see] that it had horns and wings’. James is no literary stylist, but the choice of diction, the brevity of the description, and the evocation of the landscape convey Parkins’ terror faultlessly.

Parkins reaches the Globe Inn, dines with the Colonel and retires for the night. On his way to his room he meets the ‘boots’ (the man whose job is to clean the guests’ footwear and coats) who tells him that something dropped out of his jacket pocket as he was brushing it and that he put it on the chest of drawers. It is difficult to see what purpose this episode serves. It reminds Parkins of the object he found, I suppose, but it also, perhaps, allows the reader to speculate whether the ‘boots’ has substituted another object for the one that was found.

Parkins discovers that the object is a bronze whistle. He cleans it and discovers two inscriptions. The first is set out in a diamond pattern and probably reads ‘fur, fla, fle, bis’. Scholars have had a field-day with this: if read as fur, flabis, flebis, it means something like ‘you will steal, you will blow, you will weep’; another arrangement could mean ‘you will steal, you will blow (me) twice and go mad’. This linguistic intrigue is more evidence of James playing games with his listeners, but the inscription could also be intended to suggest that it is Parkins’ colleagues who are having fun at his expense. The point is that he is unable to interpret it. The second inscription,‘quis est iste qui venit’, is translated by Parkins as ‘who is this who is coming?’ He then says to himself ‘well, the best way to find out is evidently to whistle for him’. Of course, only James’ erudite listeners would fully understand the warning that Parkins has been unable to interpret. Is this a little game of elitism? I suppose it is, but the story is just as good (or nearly as good) if you can’t solve the Latin puzzle. And it continues to intrigue readers.

The hapless Parkins blows the whistle, twice. The description of what happens when he blows it is one of the great moments in writing about the supernatural – the sound had ‘a quality of infinite distance in it’:

It was a sound, too, that seemed to have the power (which many scents possess) of forming pictures in the brain. He saw quite clearly for a moment a vision of a wide, dark expanse at night, with a fresh wind blowing, and in the midst a lonely figure.’

Is this merely a flashback of his memory of being on the twilight beach, apparently pursued by a lone figure? Or has he, after many centuries, reawakened an ancient curse from the Knights Templar? Parkins’ trance-like state is broken only by a sudden gust against the window and ‘the white glint of a sea-bird’s wing outside the dark panes’.

Is this merely a flashback of his memory of being on the twilight beach, apparently pursued by a lone figure? Or has he, after many centuries, reawakened an ancient curse from the Knights Templar? Parkins’ trance-like state is broken only by a sudden gust against the window and ‘the white glint of a sea-bird’s wing outside the dark panes’.

What compels him to blow the whistle again is a kind of addiction. He is ‘fascinated’ by the sound, but he also longs to see the pictures in his brain once more. The second blow of the whistle breaks open the window and blows out the candles. Parkins has palpitations and imagines he has a number of fatal conditions. He is comforted only by hearing that someone else was also ‘tossing and rustling in his bed nearby’. But he is still unable to sleep because, every time he closes his eyes he sees a dark beach and ‘a man running jumping, clambering over the groynes.’ He keeps on looking back, growing weaker after each groyne. Then he sees what the man is running from: ‘a figure in pale, fluttering draperies, ill-defined’. The figure searches for the man who hides behind the tallest of the groynes.

Whenever his waking nightmare gets to this point, Parkins opens his eyes and finally decides to give up trying to sleep and to read instead. He strikes a match to light a candle and the glare startles some rats, or other creatures, that he can hear ‘rustling’ close by.

In the morning the maid who is to make up his bed asks him which one. She asks because both beds have been slept in. How can we not share Parkins’ terror at this revelation! Who, or what has been in the other bed all night? And, of course, the restless sleeper whose movements comforted him in the night and the sounds he believed to be rats now take on a horrific significance. Who has not heard such noises in the night and been comforted by the thought that someone else is awake, that they are not completely alone in the world? And who, after reading this can still be comforted by such sounds?

I first read this story when I was sixteen. I shared a room with my older brother who would often be away from home. When he was not there I took all his bedding and stuffed it in a cupboard.

Despite so many occasions that should have made Parkins question his outlook, he reaffirms his disbelief in the ‘supernatural’ in a conversation with the Colonel. Whether he is still so certain at the end of the story, we are not told. Nor do I intend to tell you what happens next nor how it ends. That might spoil your enjoyment of it. I will say that it is, at a squeeze, just possible to believe that the whole thing has been a hoax played on Parkins by his colleagues (and the story itself is also a sort of hoax played by James on his colleagues and students).

Rogers, who had goaded him the most, appears ‘early’ the morning after Parkins’ final, terrifying night. He could be there to see how well the hoax worked and to pay his co-conspirators. But the Colonel would have to have been in on it. So would the ‘boots’, the chambermaid, a little boy who sees something ‘that warn’t a right thing wiving to him’ from Parkins’ room. And the storm and a seagull would also have to be part of the conspiracy. His colleagues would have to have known his psychology in such a precise way that they could have predicted his responses to each stage of the hoax. Even if we imagine the whistle being planted, and its inscription created by Latin scholars, we cannot explain away the extraordinary effect that blowing the whistle has on Parkins. That wonderfully described hallucination or possession or however you account for it remains the central and chilling mystery of the story.

This story, along with M. R. James’ other ghost stories is still available for a few pounds, as is a Kindle download version. Buy it, read it, decide for yourself. But if you should find a whistle on a beach…