photo by F.W.Kent, from the collection of University of Iowa

*

by Juliet West

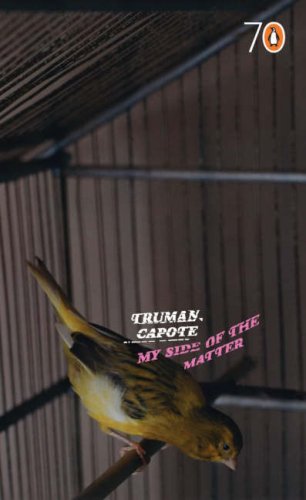

I discovered ‘Miriam’ by chance. Browsing the shelves of my local library, I noticed a slim paperback almost hidden between two far weightier volumes. The book was a 53-page Pocket Penguin called My Side of the Matter, a collection of four short stories by Truman Capote. I knew very little about Capote. A few dim connections surfaced in my mind: Breakfast at Tiffany’s, Audrey Hepburn… Harper Lee. I decided to borrow the book anyway. I liked the canary on the cover.

The first story was ‘Miriam’, and the first paragraph pure exposition:

For several years, Mrs H. T. Miller had lived alone in a pleasant apartment (two rooms with kitchenette) in a remodelled brownstone near the East River. She was a widow: Mr H. T. Miller had left a reasonable amount of insurance. Her interests were narrow, she had no friends to speak of, and she rarely journeyed farther than the corner grocery. The other people in the house never seemed to notice her: her clothes were matter-of-fact, her hair iron gray, clipped and casually waved…

This seemed an exercise in tell, don’t show. Yet I was intrigued by Mrs H. T. Miller, by the loneliness and formality of her life. Capote’s muted description had a tragic subtlety about it – ‘kitchenette’, ‘pleasant’, ‘reasonable’, ‘matter-of-fact’ – which could only foreshadow something more discomfiting.

The suggestion of menace builds with the blunt opening of the second paragraph: ‘Then she met Miriam’. Miriam, a girl of around ten or eleven, appears on a snowy night when Mrs Miller decides, uncharacteristically, to watch a film at the local movie theatre. She notices the girl standing close to her in the queue:

Her hair was the longest and strangest Mrs Miller had ever seen: absolutely silver-white, like an albino’s. It flowed waist-length in smooth, loose lines. She was thin and fragilely constructed…

Mrs Miller felt oddly excited, and when the little girl glanced towards her, she smiled warmly.

Mrs Miller chats to the girl as they wait in a lounge to go into the theatre. The conversation is awkward, and the child displays an odd, arch manner. When Mrs Miller discovers that they share the same first name, she tries to elicit some kind of reaction from the little girl: “But isn’t that funny?” says Mrs Miller. “Moderately,” Miriam replies.

Mrs Miller chats to the girl as they wait in a lounge to go into the theatre. The conversation is awkward, and the child displays an odd, arch manner. When Mrs Miller discovers that they share the same first name, she tries to elicit some kind of reaction from the little girl: “But isn’t that funny?” says Mrs Miller. “Moderately,” Miriam replies.

After the movie, Mrs Miller returns to her quiet apartment. Days merge into a lonely blur as the city is silenced by a week of unending snow. One evening, while Mrs Miller is in bed reading a newspaper, the doorbell rings. Miriam has somehow discovered Mrs Miller’s address, and she expects to be invited in.

The story develops into a deeply unsettling tale, a psychological horror which is all the more disturbing because it is so finely wrought. Miriam wanders around Mrs Miller’s apartment, passing comment on the furnishings and the ‘sad’ imitation roses. She peers into the covered birdcage and asks if she may hear the canary sing. “Leave Tommy alone,” says Mrs Miller. “Don’t you dare wake him.” Yet when Mrs Miller disappears into the kitchen to make Miriam a jam sandwich, the canary does begin to sing. If you read this story, you will feel the helpless, uncanny dread of this moment – a sinister turning point in the narrative.

In subsequent months I read more of Capote’s short stories, as well as his novel The Grass Harp and his self-styled ‘non-fiction novel’, In Cold Blood. While I admired everything I read, for me, nothing matched the power of that initial encounter with Truman Capote.

Just a few weeks ago I discovered something new about ‘Miriam’. I was shopping in a town I seldom visit, and noticed that a small independent bookshop was closing down. All stock half price, said the poster in the window. As I stepped through the doorway clutching my shopping bags, the bookseller – a white-haired man, apparently drunk – shouted at me: “You’re not coming in here with your WHSmith’s bag! It’s all bloody Smith’s fault!”

I told him I had only bought envelopes and a newspaper in Smith’s. After looking me up and down, he relented. “Go on then,” he said. “As I happen to like your boots.”

I told him I had only bought envelopes and a newspaper in Smith’s. After looking me up and down, he relented. “Go on then,” he said. “As I happen to like your boots.”

I spent a few awkward minutes browsing the shelves while the bookseller chatted with a female friend. Then, in a corner of the shop, I spotted a copy of The Paris Review Interviews, Vol. 1. The book featured interviews with legendary writers and poets, including Elizabeth Bishop, T S Eliot and Truman Capote. Red pen marked the spine, and the bright yellow cover was smeared with dust. The price was £14.99. Still, at half price, I reckoned it was a bargain.

I read the Truman Capote interview that evening. It’s dated 1957, when Capote was in his early thirties (he was just twenty when ‘Miriam’ was published in 1945). The interview is an absolute treat, offering several gems on short story technique, including this response to the question of ‘control’ in prose:

By control I mean maintaining a stylistic and emotional upper hand over your material. Call it precious and go to hell, but I believe a story can be wrecked by a faulty rhythm in a sentence – especially if it occurs toward the end – or a mistake in paragraphing, even punctuation. Henry James is the maestro of the semicolon. Hemingway is a first-rate paragrapher. From the point of view of ear, Virginia Woolf never wrote a bad sentence. I don’t mean to imply that I successfully practice what I preach. I try, that’s all.

A few pages into the interview, Capote is asked whether he still likes the stories he wrote long ago. His answer is ‘Yes’, but for one exception:

Not ‘Miriam’, which is a good stunt, but nothing more. No, I prefer ‘Children on Their Birthdays’ and ‘Shut a Final Door’…

I was amazed. What a fool I felt! In my eyes, ‘Miriam’ was a masterpiece of uncanny fiction. I’d droned on about it to friends, and had bought the book for my brother. To hear Capote dismiss it so casually was quite a blow. A good stunt, but nothing more. Hmmph. Yet… I comforted myself with the knowledge that I wasn’t alone in loving this story. After all, Mademoiselle magazine chose to publish it in 1945, and the following year ‘Miriam’ earned an O. Henry award in the category Best First-Published Story.

I was amazed. What a fool I felt! In my eyes, ‘Miriam’ was a masterpiece of uncanny fiction. I’d droned on about it to friends, and had bought the book for my brother. To hear Capote dismiss it so casually was quite a blow. A good stunt, but nothing more. Hmmph. Yet… I comforted myself with the knowledge that I wasn’t alone in loving this story. After all, Mademoiselle magazine chose to publish it in 1945, and the following year ‘Miriam’ earned an O. Henry award in the category Best First-Published Story.

I re-read the story and compared it to ‘Children on Their Birthdays’, published three years later. It’s interesting that, in both stories, the narrative centres around the appearance of a strange child: young Miriam and Miss Lily Jane Bobbit. Both girls are precocious and superior; both girls have the upper hand over a dowdy older woman. But while one is fantastical and surreal, the other is grounded in reality. Miriam is an eerie, ambiguous presence, whereas Miss Bobbit is palpably real.

‘Miriam’ plays with the reader’s emotions, owing much to the tradition of the doppelganger in folklore and fiction. Did Capote subsequently decide this approach was somehow tricksy and dishonest – too much of a ‘stunt’?

I couldn’t help but wonder about the judgement of writers on their own work. They can be savage self-critics. When Tolstoy was asked about Anna Karenina some years after its publication, he said: “I assure you that this vile thing no longer exists for me.”

‘Miriam’ was Capote’s breakthrough story, and as such, did it become tiresome through familiarity? It’s akin to the successful pop band that grows to loathe its first hit single: the single it’s forced to play at every gig for the rest of its career. But, just as some pop bands evolve from those jangly three-chord crowd-pleasers, most writers learn from early successes. As Capote said in his Paris Review interview: ‘Joyce could write Ulysses because he could write Dubliners.’

One thought on “Miriam by Truman Capote”

Comments are closed.