by Ellie Piddington

Truman Capote, on his death in August 1984 at the age of fifty-nine left behind a small, intriguing body of work: non-fiction essays, stories and novels equalled by only a few of his contemporaries. Now endorsed by critics as one of the most prominent post-war American writers, Capote has been largely viewed as a writer who, as Aleb Kerbs wrote in the New York Times obituary, “squandered his time, talent and health on the pursuit of celebrity, riches and pleasure”.

Truman Streckfus Persons was born in New Orleans on September 30th, 1924. He later adopted the surname of his stepfather, Joe Capote, a Cuban-born New York businessman. Capote was the son of Arch Persons, a non-practising lawyer, and Lillie Mae Faulk Persons, a local beauty in her Monroe County hometown, who committed suicide in 1953. Whilst living next door to Harper Lee, who modelled the character of Dill in To Kill A Mockingbird (1961) on Capote, he was raised by his unmarried cousins and aunts in the small southern town of Monroeville, Alabama. In 1942 Capote secured his first and last regular job as a messenger and office boy at The New Yorker. His biographer Gerald Clarke records that before the first week was out, two elevator men were so confused by the appearance of the androgynous and diminutive Capote that they bet a dollar as to his gender. He was fired in 1944 by the editor, Harold Ross, after an incident at a reading by Robert Frost in New England.

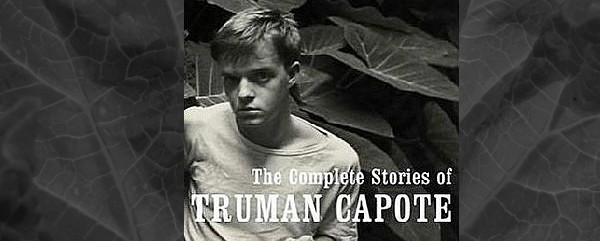

In the spring of 1946, Carson McCullers, having established her reputation as a writer with the publication of The Heart is a Lonely Hunter (1940), gained Capote admittance to a writer’s colony at Yaddo near Saratoga Springs. Professional jealousy caused them to fall out soon after. His short story ‘Miriam’ was published in Mademoiselle in 1946 and by the publication of his Other Voices, Other Rooms (1948) he was already the talk of literary circles based on a handful of short stories. Carlos Baker, in the Sunday New York Times, reviewed the Other Voices, Other Rooms as cathartic self-absorption. Though he denied it for many years, Capote was eventually to admit the novel was semi-autobiographical, the fact he hadn’t realised this point earlier was “unpardonable self-deception”. The Times critic Orville Prescott praised the “potent magic” of the prose, and Diana Trilling in The Nation commented on his striking “literary virtuosity”, but decried the “artistic-moral purpose” which she felt to be that of men turning to homosexual love. The dust-jacket of his debut novel is described by Capote’s biographer George Plimpton as “certainly the most famous book-jacket portrait of contemporary letters”. The photograph, taken by Harold Halma, shows a girlishly pretty Capote reclining on a sofa. In later years he would become paunchy and balding.

Between 1949 and 1954 Capote published a series of short stories and a novel, The Grass Harp (1951) which was performed on stage, as was his short story ‘House of Flowers’ (1954). He also wrote the screenplay for John Huston’s Beat the Devil, released in 1954. Capote was a gifted journalist as well as novelist; notably his 1956 article, based on his travels to Moscow with Porgy and Bess, ‘The Muses are Heard’, followed by his profile of Marlon Brando ‘The Duke in his Domain’.

The year after Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1958) was published, Capote began to research the mass murder of a family in rural Kansas. The resulting non-fiction novel, In Cold Blood (1966), made Capote the instant star of numerous television talk shows. The novel was almost universally praised, with John Hersey calling it “a remarkable book”. After publication of In Cold Blood, Capote published little, stating he was writing a long novel examining society in rich America. In 1975 he published in Esquire magazine excerpts of this manuscript telling apparently true and scandalous stories of his famous friends, whose friendships he subsequently lost forever. In later years he became progressively drawn to alcohol and drug abuse. He died in the Los Angeles home of friend Joanne Carson, leaving just a few pages of his incomplete “masterwork” Answered Prayers. The coroner’s report stated the cause of death was “liver disease complicated by phlebitis and multiple drug intoxication”. Summer Crossing, his incomplete first novel, was sold at Sotheby’s, New York in 2004.

Reynolds Price suggests that Capote’s earliest stories reflect his reading of the time – that of his contemporaries, the fellow southerners, Carson McCullers and Eudora Welty. His ‘Jug of Silver’ (1945) uses small town humour reminiscent of McCullers’s early stories. ‘Children on Their Birthdays’ (1948) and ‘My Side of the Matter’ (1945) bear similarity to Welty’s ‘Why I Live at the P.O.’. Yet, by the late 1940s the tone of his stories was his own. Price suggests Capote’s short stories often explore, “sexual and familial mysteries” as in ‘The Headless Hawk’ (1946), ‘Shut a Final Door’ (1947) and ‘Tree of Night’ (1945). Homosexuality was an ever-present and complex reality to Capote, yet at the heart of some of his most potent short stories is not homosexuality, but the deeply affectionate relationship between Capote as a child and his cousin Miss Sook Faulk, with whom he shared a home – expressed in ‘A Christmas Memory’, ‘The Thanksgiving Visitor’ and ‘One Christmas’.

The influence of Capote’s southern up-bringing is evident in his work; his characters are frequently misfits, eccentrics and odd-balls. The side-show midget and the one-armed barber would not seem out-of-place in the work of William Faulkner, Carson McCullers, Tennessee Williams or Flannery O’Connor. Furthermore, the language is elegant, decadent and seductive; it is easy to imagine the writer is the same youth posing so languorously in Harold Halma’s portrait. His prose remains fresh in the same way the barely post-adolescent, androgynous dust-jacket photograph of Capote endures. Babs Simpson, editor at Vogue, said of Capote, “I’m sure he always saw himself his entire life lying on that sofa. I’m sure he thought he was a beauty till the day he died”.