photo by kakisky

Stereo Past

by Morgan Omotoye

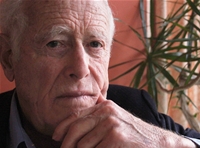

Reading James Salter’s notebooks, Edward Hirsch of the the Paris Review came upon the following line: ‘Life passes into pages if it passes into anything’. When I discovered these words, I underlined them. For me, they evoked the primal urgency of cave paintings; a talismanic power that throws light on a way to write, and a way to think about writing and even life itself. In a very real way, these lines helped clarify what it is I love about James Salter’s writing, especially his remarkable short story ‘Akhnilo’.

I first came across ‘Akhnilo’ in Raymond Carver and Tom Jenks’ American Short Story Masterpieces (though it originally appeared in Salter’s collection Dusk and Other Stories). ‘Akhnilo’ begins with Eddie Fenn waking to a strange sound. He is in bed next to his wife and, although ‘there had been many robberies and worse nearer the city’, the house is unlocked. Eddie believes the sound he heard is ‘the creak of a spring, the one on the screen door in the kitchen’. He listens. The sound continues. The sound changes. Eddie decides to investigate. He leaves his bed, then his house, and journeys into a night in which ‘the trees were like black reflections. The stars were hidden’.

Eddie draws nearer to the sound, which seems to be emanating from a barn. As he gets closer, he begins to think that what he hears are actually words: ‘They had no meaning, no antecedents, but they were unmistakably a language, the first ever heard from an order vaster and more dense than our own’. Eddie creeps forward, and from Salter we get the chilling declaration, ‘The sound hesitated’.

Eddie draws nearer to the sound, which seems to be emanating from a barn. As he gets closer, he begins to think that what he hears are actually words: ‘They had no meaning, no antecedents, but they were unmistakably a language, the first ever heard from an order vaster and more dense than our own’. Eddie creeps forward, and from Salter we get the chilling declaration, ‘The sound hesitated’.

The sound stops and Eddie can only remember four words. It is these words he desperately tries to spirit back to his home. On the way, he continually worries that if a dog barks, or a light goes on in a bedroom, he will be distracted from the words.

When he gets back to his house, his wife is waiting for him. He pushes her away. Salter writes: ‘Beneath her devotion it was dissolving, the words were spilling away.’ The words in Eddie’s mind start to evaporate, until there is ‘just one left, worthless without the others and yet of infinite value’. Eddie grabs a pen, and writes this one word down.

The noise Eddie makes on his return rouses Dena, his young daughter, from sleep, and ‘Akhnilo’ ends on the following note:

Suddenly he slumped to the floor and sat there and for Dena they had begun again the phase she remembered from the years she was first in school when unhappiness filled the house and slamming doors and her father clumsy with affection came into their room at night to tell them stories and fell asleep at the foot of her bed.

What I love about this ending is its abrupt and dramatic shift in character perspective. Throughout ‘Akhnilo’ we have been carried along with Eddie’s quest to decipher the sound, to get close to it, to understand it, protect it and, to a certain extent, own it. Then, right at the story’s terminus, we are left with the consequence of his actions – the effect his actions have on his family, and especially his daughter. It is almost as if we, as readers, are left on the threshold of another story, one in which a future Dena will revisit this moment in order to better understand herself and her father.

Another quality of this extraordinary ending is its deft handling and manipulation of time. It freezes time in the present moment: ‘Suddenly he slumped to the floor…’ Eddie Fenn, our intrepid hero, our questing knight, is stilled, encased in amber, brought low, and humbled by his inability to acquire the sound. The ending also seeps into the past, into the realm of memory: ‘The phase she remembered from the years she was first in school…’; then it nimbly encroaches on the future: ‘For Dena they had begun again…’

These agile temporal gymnastics give the story a timeless quality. ‘Akhnilo’ feels very much like a story we have encountered before, a hallucination, fragments from a dream or perhaps something more along the lines of a myth. Even the uncanny-sounding title resonates like some destination we are heading towards, or perhaps even a warning. This is a story that carries a supernatural urgency, mystifying and enticing the reader long after the final words. And this is a story that does not end, not really. ‘Akhnilo’ rebounds and reverberates. A father wakes in the night to a mysterious sound. A daughter awakes in the early hours of morning to the sounds her father makes as he tries to capture a word he has heard. It is a sort of acoustic loop.

That said, the engine that drives the story is not the sound, but the powerfully vivid character of Eddie Fenn. Though an intelligent man who ‘had, at one time, almost become a naturalist’, Eddie has failed and is marooned on the shore of his failures: ‘There was something quenched in him. When he was younger it was believed to be some sort of talent, but he had never really set out in life, he had stayed close to shore.’ After a business venture that he started with a friend collapsed, Eddie began to drink heavily: ‘His family had saved him, but not without cost.’ And it is into this life Eddie that has salvaged for himself that the enigmatic sound arrives.

That said, the engine that drives the story is not the sound, but the powerfully vivid character of Eddie Fenn. Though an intelligent man who ‘had, at one time, almost become a naturalist’, Eddie has failed and is marooned on the shore of his failures: ‘There was something quenched in him. When he was younger it was believed to be some sort of talent, but he had never really set out in life, he had stayed close to shore.’ After a business venture that he started with a friend collapsed, Eddie began to drink heavily: ‘His family had saved him, but not without cost.’ And it is into this life Eddie that has salvaged for himself that the enigmatic sound arrives.

It is important to track the various, telling mutations the sound acquires throughout the story. Initially, it is one of threat, of someone breaking into Eddie’s home. Then he suspects it might be an animal. Then he finds that it is not ‘the cricket, cicada’, but something more elusive and eerie: ‘less and less an instinctive cry and more a kind of signal.’ Eddie needs to get closer to it in order to decipher and understand it.

So he leaves his home, his family, and enters the night, which is linked lyrically in the story to the animal kingdom. Salter’s language in describing the natural world is rich and evocative, but it is also filled with threat:

In ravenous burrows the blind shrews hunted ceaselessly, the pointed tongues of reptiles were testing the air, there was the crunch of abdomens, the passivity of the trapped…

It is from this position of passivity, in a life that has not amounted to what he’d hoped it would, that Eddie Fenn means to escape.

As he beats a retreat from his home, he is described in increasingly animal terms, moving ‘quietly, like a serpent’, and dropping from his roof ‘light as a spider’. To follow the sound, he has to shed the trappings of civilisation – his home, his family – and become more animal, in order to traverse a landscape in which ‘the only galaxies were the insect voices that filled the night’. AS he escapes his home, Eddie experiences an unbridled sense of exhilaration: ‘He was moving towards the lodestar, he could feel it. It was almost as if he were falling.’

Eddie Fenn is hunting the sound. He feels it is ‘taking him where nothing he possessed would protect him, taking him barefoot, alone’. Then, as he draws closer to it, ‘inexplicably the sound altered and exposed its real core’.

Eddie believes the sound will cast him in a new and rejuvenating light. His life so far has been written in invisible ink, and the sound offers escape. It is a means towards a path bound for glory. But the sound is ultimately something he cannot reach, and perhaps more importantly, something he cannot hold on to. What he can hold, Eddie pushes away – his family: ‘His life had not turned out as he expected but he still thought of himself as special, as belonging to no one.’

The formidable beauty of this story is its ability to dramatise frailties with which we are all familiar. As Salter notes, ‘Nothing is safe except for an hour’, not even our dreams, and perhaps it is not Eddie Fenn’s lot to achieve his dreams. But despite this, what Dena remembers at the close of ‘Akhnilo’ is her father, ‘clumsy with affection’, trying to tell stories. Perhaps there is some grace in this, that, in spite of all he fears he has lost and all he has failed to achieve, Eddie Fenn still strives to forge a bond with his daughters. He tries to tell stories. Even in his defeated and dejected state, Eddie Fenn understands what stories are good for; he understands their worth.

The formidable beauty of this story is its ability to dramatise frailties with which we are all familiar. As Salter notes, ‘Nothing is safe except for an hour’, not even our dreams, and perhaps it is not Eddie Fenn’s lot to achieve his dreams. But despite this, what Dena remembers at the close of ‘Akhnilo’ is her father, ‘clumsy with affection’, trying to tell stories. Perhaps there is some grace in this, that, in spite of all he fears he has lost and all he has failed to achieve, Eddie Fenn still strives to forge a bond with his daughters. He tries to tell stories. Even in his defeated and dejected state, Eddie Fenn understands what stories are good for; he understands their worth.

In ‘Akhnilo’ we get life’s pulse, its dips and valleys through the careful delineation of the disappointments and small victories of the main character Eddie Fenn, and through Dena, who does something very important at the story’s conclusion. Although Eddie Fenn physically draws away from his family, Dena remembers him as trying his best to be close to them, and it is in this that her father might be saved: not by a supernal sound, but through his daughter’s love.

There is a cornucopia of riches to explore in ‘Akhnilo’: Salter’s luminous and hypnotic use of language; the attentive meditation on time and memory. It can be read and compared with Lore Segal’s devastating short story ‘Reverse Bug’, or Don Delillo’s ‘Human Moments in World War III’ (both these stories dealing poignantly with the subtle intrusion and ramifications of certain sounds on our consciousness). It is a story very much like the sound Eddie Fenn reveres, in that it evolves and mutates the closer we get to it. Above all, ‘Akhnilo’ is one of my absolute favourite short stories because it carries with it a mystical allure, a charge. Life passes into its pages.

~

photo of James Salter © Lana Rys

One thought on “James Salter’s ‘Akhnilo’”

Comments are closed.