photo by earl53

by Sean Martin

On 8 April 1979, Breece D’J Pancake attended afternoon Mass in Milton, West Virginia. This was nothing unusual; it was Palm Sunday and Pancake was a recent convert to Roman Catholicism. He had missed morning Mass as he was feeling sick, complaining of a headache and a cold. After Mass, he went home and drank a few beers. In the evening, he entered his neighbour’s house, looked around and sat in a chair, maybe watching the twilight thicken. Then, fatefully, the neighbour returned. Finding a drunk Pancake in her house, the neighbour declared she was going to call the police. Pancake did not wait for them to show up. He did not wait to explain that he was just idling away the time, maybe being a bit nosy, but doing nothing criminal. Instead, he returned to his own house across the yard, where dogwood and apple trees were in bloom, and emerged a few minutes later with a Savage Arms twelve-bore shotgun. He sat down in the chair beneath the apple tree in the middle of the yard, put the barrel in his mouth, and pulled the trigger.

At the time of his death, Pancake had published just six short stories, mainly in The Atlantic Monthly. His suicide at the age of twenty-six robbed American letters of one of its most distinctive voices, a loss on par with those of Sylvia Plath and John Kennedy Toole. Pancake’s stories, of the lives of the rural poor, the hill people of the Appalachians, are masterpieces of pared down prose, insight and, ultimately, compassion for people who, like himself, were never able to get away from ‘the prisoning hills’ (as he dubbed them) of West Virginia. In 1982, Pancake’s editor at The Atlantic Monthly, Phoebe-Lou Adams, said, “In thirty-some years at The Atlantic, I cannot recall a response to a new author like the response to this one. Letters drifted in for months, obviously from people who knew nothing about him, asking for more stories, inquiring for collected stories, or simply expressing admiration and gratitude. Whatever it is that truly commands reader attention, he had it.”

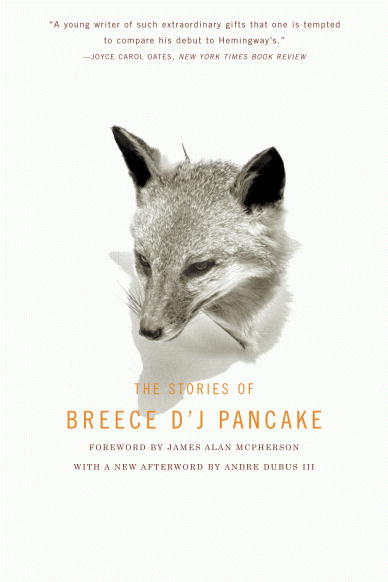

The Stories of Breece D’J Pancake, containing twelve short fictions, finally appeared in 1983 and the critical response made Pancake’s premature death all the more keenly felt. After reading just one story, ‘Hollow’, Andre Dubus wrote: ‘I wish someone could have saved him.’ Joyce Carol Oates compared him to Hemingway; Jayne Anne Phillips – a fellow West Virginian – to the Joyce of Dubliners. Subsequent admirers have included Raymond Carver, Sam Shepard, Carolyn Forché, Peter Davison and Margaret Atwood. All recognised a formidable talent had been silenced long before its time.

The Stories of Breece D’J Pancake, containing twelve short fictions, finally appeared in 1983 and the critical response made Pancake’s premature death all the more keenly felt. After reading just one story, ‘Hollow’, Andre Dubus wrote: ‘I wish someone could have saved him.’ Joyce Carol Oates compared him to Hemingway; Jayne Anne Phillips – a fellow West Virginian – to the Joyce of Dubliners. Subsequent admirers have included Raymond Carver, Sam Shepard, Carolyn Forché, Peter Davison and Margaret Atwood. All recognised a formidable talent had been silenced long before its time.

Breece Dexter Pancake was born in Charleston, West Virginia, in 1952, and attended school in the small town of Milton. His parents were middle-class, or lower middle-class – accounts differ. He was certainly not of hillbilly stock, despite cultivating that persona when he was at the University of Virginia. According to his teachers, he always strove to improve himself; to become ‘an aristocrat in blue jeans’, as his writing tutor, James Alan McPherson, remembered in his foreword to the Stories. But Pancake did not fit into Charlottesville society, where McPherson taught him on the Masters writing programme. ‘A writer, no matter what the context,’ McPherson observed, ‘is made an outsider by the demands of his vocation, and there was never any doubt in my mind that Breece Pancake was a writer.’

Small press magazines published Pancake’s first stories in 1976. They were ‘The Mark’ and ‘Hollow’ (the story that had so impressed Andre Dubus on first reading). ‘The Mark’ is Southern Gothic minimalism – a tale of incest and failed pregnancies, Appalachian voodoo in the form of rabbit’s blood, and a snake-swallower at the local travelling fair. In ‘Hollow’, Bud, a miner dying  of lung disease, loses Sal, his lover. Grief-stricken, he wanders the snowy woods and kills a deer, tearing its unborn foal out of its womb, butchering the doe until he has enough meat for his pan. The story finishes with Bud about to return to the mine to call a strike. These two striking stories may have been Pancake’s first steps into the literary world, but his breakthrough came late the following year, when The Atlantic Monthly published ‘Trilobites’.

of lung disease, loses Sal, his lover. Grief-stricken, he wanders the snowy woods and kills a deer, tearing its unborn foal out of its womb, butchering the doe until he has enough meat for his pan. The story finishes with Bud about to return to the mine to call a strike. These two striking stories may have been Pancake’s first steps into the literary world, but his breakthrough came late the following year, when The Atlantic Monthly published ‘Trilobites’.

In many ways the signature Pancake story, ‘Trilobites’ records the thoughts of Colly – a young man whose father has died, leaving their farm to Colly and his mother. Colly knows he doesn’t have farming in his blood, saying to himself, whilst on his tractor: “Yessir, Colly, you couldn’t grow pole beans in a pile of horseshit.” His mother knows this too, and is on the verge of selling up and moving to Akron, Ohio. Colly has a brief liaison with Ginny, a former girlfriend returned from college, and is reminded of how lost he is, living in Rock Camp, West Virginia – the fictionalised version of Pancake’s hometown of Milton. Colly decides to spend one last night at home before leaving forever:

I’ve got eyes to shut in Michigan – maybe even Germany or China, I don’t know yet. I walk, but I’m not scared. I feel my fear moving away in rings through time for a million years.

It is one of those rare moments in Pancake’s work where there does seem to be a future after all, even if it is only as bright as the light of the evening storm Colly watches from the farm’s porch.

‘The Mark’, ‘Hollow’ and ‘Trilobites’ introduced Pancake as a writer who emerged fully formed. They revealed his fine ear for Appalachian dialogue, his sense of how the land and its history could mould people’s lives unforgivingly, his sense of loss and helplessness and, just occasionally, of a tentative hope. What Pancake could have gone on to write is probably not worth dwelling on; we could ask the same of Plath or Toole. So perhaps it is best to read and re-read Breece Pancake’s stories – allowing them to give us something different each time we go back, to find some new treasure brought up from the depths of the West Virginia earth.

Jayne Anne Phillips, herself a native of that earth, knew it well and recognised the profundity and beauty of Pancake’s work:

We find here a landscape preserved in rich sadness because it is forgotten, a people whose lives are informed by loss, wrenching cruelty, and the luminous dignity which marks the endurance of all that is most human.

thank you Sean. I really enjoyed reading this as I’ve gotten to know another great short story writer. I read “Hollow ” and now I’m reading “Trilobites”. both are astonishing. his work reminds me of Mary Wilkins Freeman. she was considered a Regionalist as well with a fine ear for the dialect of the day. she concentrated on the downtrodden of her new England town. it’s really a tragedy that we lost him at such a young age