photo by justyna furmanczyk

Short Stories and the Power of ‘Not Knowing’

by David Constantine

I began writing stories, of a sort, at university but didn’t publish one till years later, in Stand, and a collection (Back at the Spike) only years after that, with Ryburn – which became Keele University Press, which became Edinburgh University Press, which, anxious to be shot of it, soon declared the title out of print. I should have carried on writing stories anyway, as I should poems, with or without the doubtful encouragement of such publishers. So when Bloodaxe Books began in the late 1970s and Comma Press in 2003, and Neil Astley asked me for poems and Ra Page for stories, I counted myself very lucky indeed, and have been with those two ever since, greatly encouraged by both and glad to be among their writers.

There is little agreement as to what a short story is, but, most often, you recognize one when you meet one. They may be very short, but even a quite long piece of prose fiction can also qualify. And it is no good saying they must have a beginning, a middle and an end, or that they must close (or open) at that required end. They might. But on the other hand, they might not. Myself, I re-invent the genre every time – by which I don’t mean that I am amazingly inventive, more that I can’t remember how I went about it last time. Or – more precisely – I can’t see how the way I went about it last time will help me this time. Truly, it puzzles me and I feel ill-equipped. Same with poems.

Now, at some level it may – perhaps even must – help to have written a good deal in both genres already. You have a stock of possible strategies. But your premise has to be that the project in hand is unlike any other you have been faced with previously, and if that premise brings with it a feeling of ignorance, of not knowing  where to start, that, in my experience, is a good thing. Obviously, it must not last for ever, nor become a conviction that you are utterly incapable – but a puzzlement, feeling dépaysé, rather at a loss, that is far more likely to be productive than the belief that, for this little task in hand, Strategy A, B or C would serve. Altogether, with a poem or a story, deciding at a glance that you ‘know how to go about it’ is more likely to end in tears than in rejoicing.

where to start, that, in my experience, is a good thing. Obviously, it must not last for ever, nor become a conviction that you are utterly incapable – but a puzzlement, feeling dépaysé, rather at a loss, that is far more likely to be productive than the belief that, for this little task in hand, Strategy A, B or C would serve. Altogether, with a poem or a story, deciding at a glance that you ‘know how to go about it’ is more likely to end in tears than in rejoicing.

I suppose I write the kind of stories that somebody would write whose first love is poetry. For a start – or, really, before the start – neither poem or story is biddable. I can’t simply decide that now, this morning, this evening, I will write one or the other. They are not at my command. I don’t think this is very unusual. I know quite a few writers whose feeling is that the poem bids them, commands them; not the other way round. In that view of it, ‘being biddable’ is a virtue the writer cannot very well do without. But not too biddable. Quite a lot of promptings turn out to be misleading or downright false. So you have to attend, be open, willing, available – but critically. I have written stories or poems because I was asked to – for an anthology, or for some public place or occasion – but not often, and only because the commission itself answered some desire (and ability) in me to address that topic. And being asked to do something is itself perhaps only a more public version of what I do anyway, which is wait around until the possibility of a story or a poem ‘comes to me’.

Poem and story are different genres, each has its own resources, and now I shall concentrate on stories. But I shall be able to say better how I work in that genre if, as I proceed, I compare its demands with those of poetry.

I abide by Carlos Williams’ rule for the making of a poem – ‘No ideas but in things’ – and apply it equally to the making of stories. My stories never start in an ‘idea’, unless taking that word at its root meaning: ‘something seen’, an image. But even then I should want the other senses to be involved. My stories start in some particular and very concrete situation, real or imagined, in which I think I detect the possibilities of an opening line (I could show in every one of my published stories what its beginning was – but I’d rather not). I couldn’t write a story to prove or disprove a thesis, support or demolish an argument, advance or hinder any opinion or ideology. I do plenty of that sort of writing and I know how unlike writing stories (and poems) it is. I start a story because some concrete image or situation prompts or pesters or forces me to. And I don’t know where I am going when I start. I’ve met writers who won’t start the story until they know pretty exactly where they are going in it, who work it all out in detail in advance. But that’s not my procedure. Sentence by sentence in every new story I feel my way.

As well as the concrete image, before I can begin I also need a voice, a tone of voice – for the telling of the story and for one or more of the characters in it. And best if I can hear a voice as a rhythm first, an intonation, perhaps as an accent, then, with luck, I may hear some words, a sentence or two, that such a voice, as narrator or character, might say. And only then am I ready to risk it and make a start.

I said just now that sentence by sentence I feel my way; I could also say that I listen, for more words in that particular tone of voice. If I lose my way it is because I have lost the voice, not listened closely enough, have let the true voice, the only voice that will do for the story, go out of my hearing. This isn’t a mystical or even a mysterious procedure. It is entailed by my sense that the story will open to me only if I attend.

A writer who primarily writes poems may be reluctant when writing a story to use language merely as a means to an end, however right, proper and necessary that end may be. Such a writer, more accustomed to the lyric mode than the epic, may find it ridiculously difficult or tiresome to write sentences that ‘merely’ advance the plot – to get a character to walk down a corridor, turn left at the bottom, enter the third door on the right and put a copy of Alice in Wonderland on the CEO’s gigantic desk, for example. A lifetime’s obsession with finding the words, the right words, in the right order, in the only fitting rhythm, may almost disable you in the business of using them to get from A to B. That’s the most usual characteristic (or failing, if you don’t like it) of poets writing stories: their language draws attention to itself. In self-defence, I’d say that, ideally, the fiction comes into being – is made – in the very making of sentences. The whole living sense of the thing, what it does to the reader, is engendered by the language advancing in its own peculiar rhythm. No poet telling stories quite wants to subordinate his or her language even to the good and necessary purpose of telling the story. This consideration may then also affect and even quite determine the handling of such larger components as plot, argument and, altogether, chronological progression.

A writer who primarily writes poems may be reluctant when writing a story to use language merely as a means to an end, however right, proper and necessary that end may be. Such a writer, more accustomed to the lyric mode than the epic, may find it ridiculously difficult or tiresome to write sentences that ‘merely’ advance the plot – to get a character to walk down a corridor, turn left at the bottom, enter the third door on the right and put a copy of Alice in Wonderland on the CEO’s gigantic desk, for example. A lifetime’s obsession with finding the words, the right words, in the right order, in the only fitting rhythm, may almost disable you in the business of using them to get from A to B. That’s the most usual characteristic (or failing, if you don’t like it) of poets writing stories: their language draws attention to itself. In self-defence, I’d say that, ideally, the fiction comes into being – is made – in the very making of sentences. The whole living sense of the thing, what it does to the reader, is engendered by the language advancing in its own peculiar rhythm. No poet telling stories quite wants to subordinate his or her language even to the good and necessary purpose of telling the story. This consideration may then also affect and even quite determine the handling of such larger components as plot, argument and, altogether, chronological progression.

The epic’s natural movement is chronological (I know, it can be subverted), recounting events in a sequence. But much in the lyric prefers to move laterally, or sometimes with a musical ritardando, or even not to move forward at all – pausing in a sort of simultaneity, the images suspended, floating, briefly co-existing. These are only possibilities and matters of varying emphasis. In practice, if you engage in the telling of a story, the epic must predominate, but much of the lyric, its character and strategies, can be operative too. The short story, such a fluid form, allows it.

I said earlier that a piece of fiction can’t be defined as a short story merely by its length. But, more importantly, a short story, whatever its length, should never be a piece of writing that has been abbreviated. A good short story leaves much unsaid (see below), but if you abbreviate the story you deprive the reader of the promptings towards those unsaid things. The story should go as far as to initiate an opening up, a reaching further; if it halts too soon, before that point, it fails. When the story does end, it should linger, still working, in the reader’s consciousness. An abbreviated story won’t do that.

‘Closure’, much advocated and striven after, is neither possible nor desirable in life – so it can’t be in fiction or poetry either. In life and in writing, closure is a false goal. Of course, people want, and often need, to ‘get over things’, particularly bad things. They want to go on living – they want to live and enjoy a life they can call their own. But closure, even if possible, wouldn’t help in that. And nor will any fiction or poetry that pretends or acts as though it might. A story might help if, as it ends, it opens up possibilities of further life. The very movement of such an ‘opening up’ is itself hopeful, and it can counteract and even override other elements in a story – with consequences still lingering or developing as the fiction ends. The mind, quickened in this way to the continuing and developing possibilities of more life is, I believe, left energized and fortified — better equipped.

So: no closure. And in accordance with that dictum I shall end here and now, abruptly, leaving the rest unsaid.

~

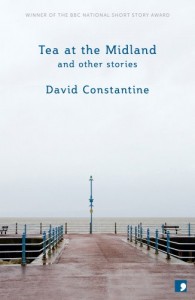

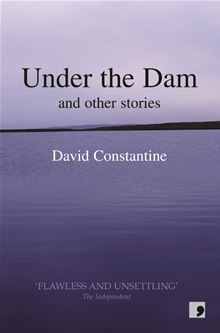

David Constantine, born 1944 in Salford, Lancs, was for thirty years a university teacher of German language and literature. He has published several volumes of poetry (most recently – 2009 – Nine Fathom Deep); also a novel, Davies (1985), and four collections of short stories: Back at the Spike (1994), Under the Dam ( 2005), The Shieling (2009) and Tea at the Midland (2012). He is an editor and translator of Hölderlin, Goethe, Kleist and Brecht. His translation of Goethe’s Faust, Part I was published by Penguin in 2005; Part II in 2009. OUP published his translation of the The Sorrows of Young Werther in 2012. He was the winner of 2010 BBC National Short Story Award. With his wife Helen he edited Modern Poetry in Translation, 2003-12.

David Constantine, born 1944 in Salford, Lancs, was for thirty years a university teacher of German language and literature. He has published several volumes of poetry (most recently – 2009 – Nine Fathom Deep); also a novel, Davies (1985), and four collections of short stories: Back at the Spike (1994), Under the Dam ( 2005), The Shieling (2009) and Tea at the Midland (2012). He is an editor and translator of Hölderlin, Goethe, Kleist and Brecht. His translation of Goethe’s Faust, Part I was published by Penguin in 2005; Part II in 2009. OUP published his translation of the The Sorrows of Young Werther in 2012. He was the winner of 2010 BBC National Short Story Award. With his wife Helen he edited Modern Poetry in Translation, 2003-12.

…”drive each one” sorry my finger slipped on my tiny keyboard!

I love this because you’ve answered a question I’ve always posed to myself. poetry was my first love and I find that when I write I dwell too much on description, on trying to capture an elusive feeling to the detriment of plot. of course I need help with both poetry and short stories, but it helps knowing that its not that I can’t write, or that I don’t know how to plot, but that different parts of the brain takes over. I just need to learn how to drive h1 so that I get to my destination