photo by Carlos Porto

by Jemma Draycott

Many of the greatest love affairs happen purely by chance — from meeting a beloved to discovering a song seemingly ‘meant’ for you, to finding a writer whose stories truly touch you. This happened to me when I stumbled across Hanan Al-Shaykh’s work… the spark of new love was ignited.

a writer whose stories truly touch you. This happened to me when I stumbled across Hanan Al-Shaykh’s work… the spark of new love was ignited.

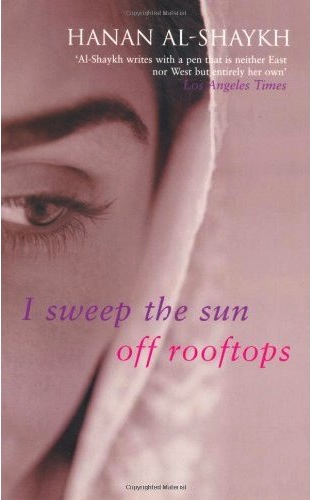

I first discovered Al-Shaykh through one of her novels, Beirut Blues. Her writing captured my attention immediately and so, as an avid fan of the short story form, I sought out her collection I Sweep the Sun Off Rooftops. I was moved by her writing and I believe that all who read Al-Shaykh’s work will be moved on some level too, as she draws you into the richness of her Middle Eastern heritage.

‘The Scratching of Angels’ Pens’ is one of the shorter stories in I Sweep the Sun Off Rooftops, but it held me from the first word to the last. This exquisite story paints a picture of Middle Eastern tradition and religious expectation. The opening paragraph is an endless list of rules that the young, recently widowed protagonist Shadia is ordered to follow:

Don’t use the jug with the long spout to do your ablutions! Don’t wash your face with scented soap! Don’t admire the moon! Don’t bleach your sheets! You mustn’t raise your voice above a whisper, especially if there’s a man in the next room!

It is a time of mourning and we see Shadia surrounded by ‘rows of women — some wailing, some silent — wishing she could be left alone for a moment’. Against this backdrop, Shadia is a figure of rebellion, someone who refuses to follow tradition. We soon learn that she is a woman of scandal; she left her first husband and child for her second husband. The women who surround her declare:

“Come on! Given a bit of time, she’ll go back to her first husband and start bringing up this daughter of hers again. See, the Almighty’s taken His revenge.”

But Shadia’s devotion to her second husband is undeniable, particularly in the following extract, a scene that shows the couple in the hospital after his accident. The physical contact between them is not sexual, but simply full of love:

Sometimes he showed her the tip of his tongue and she dropped a kiss on his mouth and brought her hair close to him, putting a lock of it in his palm and closing his fingers around it, rejoicing when she felt him pressing on it.

In this tender display of feeling, the reader, too, is moved. Despite the cultural references to Middle Eastern traditions, Al-Shaykh does not alienate her western readers. Indeed, by creating images of great depth and weight, her scenes become universal, and she bridges the gap between cultures.

Because the women around Shadia consider her second marriage very shameful, we feel, with Shadia, the conflict between the forces of emotional, ‘lived’ truth and tradition. Al-Shaykh’s work suggests that emotional honesty is the greater truth, whatever its risks. She poses the question that all of us face at one time in our lives: should we follow our emotions or follow social expectation? The scene in which Shadia sleeps with her second husband is beautifuly evoked:

…she was sure she had been created for this moment. She closed her eyes, savouring the peace of mind that she thought had been taken away from her for good.

She writes of the power of love with freshness and simplicity. There are no tired phrases or clichés, and consequently, we believe in the strength of Shadia’s devotion.

Even the scornful women are made entirely human. When Shadia questions which husband she will meet in paradise, our perceptions of these women are altered entirely:

Her question, asked in a heartfelt rush of despair and terror, rolled over ears that had never heard an amorous whisper, a kind word or beautiful melody, and was buried in hearts that knew only frustration and anxiety.

In just a few simple words, Al-Shaykh describes the love that is lacking in their lives; how they have never heard a ‘beautiful melody’. As a reader, I felt pity for them, and even a sense of understanding. This three-dimensionality, for me, is the mark of a great writer. On these pages, as in real life, the good is blended with the bad; the humorous with the heart breaking.

In just a few simple words, Al-Shaykh describes the love that is lacking in their lives; how they have never heard a ‘beautiful melody’. As a reader, I felt pity for them, and even a sense of understanding. This three-dimensionality, for me, is the mark of a great writer. On these pages, as in real life, the good is blended with the bad; the humorous with the heart breaking.

Because she writes of Arab women, it is easy for an author such as Hanan Al-Shaykh to be too neatly categorized as a ‘feminist writer’. Yet her writing reflects an interesting point made by Anastasia Valassopoulos, in her study of Contemporary Arab Women Writers: Cultural Expression in Context:

Placing emphasis, instead, at least in theory, on including all women by accepting the multiplicity of each woman’s identity and self-identification, feminists are now urged to respect difference, affirming the singularity of each woman’s experiences and struggle, and validating self-understanding and self-analysis.

In Al-Shaykh, women are fully rounded individuals, not merely symbols of their sex. It is experience, as Shadia learns, that shapes us as people and changes our lives. Without experience and struggle, we are all simply moulds of society and expectation.

The last section of the story reveals the horrors Shadia risks in the afterlife. There are ‘Women whose faces had been burnt and whose tongues lolled out onto their chests, because they asked for their husbands to divorce them for no reason’. But, in the final lines, Al-Shaykh reveals a heartbreakingly beautiful conclusion that Shadia has reached for herself:

Shadia nodded her head calmly, accepting her fate. “I don’t care,” she said, and rid herself of two images: herself in bed with her first husband, and lying with him on the pearly white ground of Paradise.

For Shadia, despite of the terrors she believes she will face, she chooses the love she feels for her second husband.

Al-Shaykh portrays this act of courage in a tremendously heartfelt way. Here and throughout this collection, we find a writer who loves people and who writes about them with power, daring and insight.

Take a leaf out of my book and fall in love with her stories now.