photo by Sanja Gjenero

by Konstantinos Tzikas

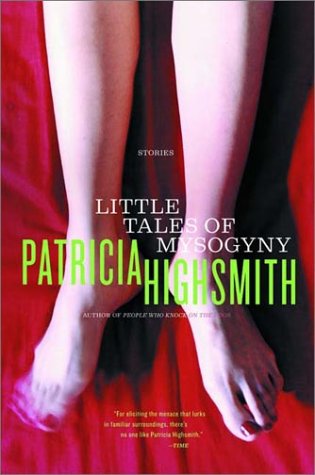

When it was originally published, Patricia Highsmith’s Little Tales of Misogyny was met with much suspicion – was it a book that condemned or encouraged misogyny? Did it take a clear, unambiguous view of the whole issue? In fact, this short story collection refuses to surrender to clearly demarcated categories, tiptoeing instead between ‘serious’ fiction and fairy tales, melodrama, magic realism and satire.

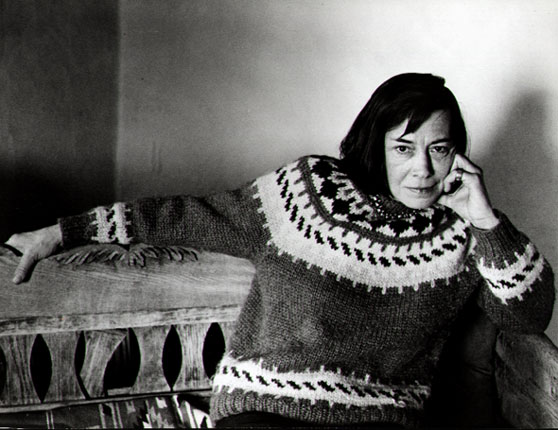

The suspicion the collection was faced with is not unlike the suspicion that has been directed towards the author herself throughout her career. Her perceived misogyny has been a source of  contention, as has her literary merit: is she a genre writer, or a genuine representative of high-brow literature? At the very least, her short stories are regularly overlooked in favour of her more well known novels, like the Ripley series.

contention, as has her literary merit: is she a genre writer, or a genuine representative of high-brow literature? At the very least, her short stories are regularly overlooked in favour of her more well known novels, like the Ripley series.

I’ve often found Highsmith’s work both perplexing and engaging, yet, for me, there is no question about her value as a writer.

Little Tales of Misogyny seems, on one hand, firmly rooted in Franz Kafka’s stories, especially his very short stories. This literary debt is particularly evident in the rhythm of her words. Like Kafka’s shorts, the stories often end abruptly, brusquely. On the other hand, one can easily discern the influence of both Albert Camus’ existentialism — regardless of how much the French-Algerian writer dismissed the term — and of his absurdism. In Little Tales of Misogyny, it is the absurdism that shines through, rather than misogynistic stories told at the expense of women.

These defining elements work perfectly together; the abrupt endings to Highsmith’s stories appear almost as as form of punctuation amid her rather unconventional, unpredictable, absurd plots. And it is precisely her idea of closure which informs much of the brutal absurdism in the stories. She willfully abandons any sense of hope, reason and order, and almost aloofly casts off her heroines in cruel and irrational scenarios, as in the abrupt demise of Pamela in ‘The Middle-Class Housewife’, a story about the meeting of a feminist group which turns into full-blown chaos:

But it was a two-pound tin of baked beans that did for Pamela, catching her smack in her right temple. She died within a few seconds, and her assailant was never identified.

Highsmith may treat her women cruelly – disposing of her heroines in a mere sentence or phrase – but she is not insensible to their plights; she turns her real attack upon other forces. In ‘Oona, the Jolly-Cave Woman’, the victimised heroine operates in a prehistoric society, though her sufferings deliberately bring to mind analogous miseries still endured in modern society: ‘Oona was constantly pregnant and had never experienced the onset of puberty, her father having had at her since she was five, and after him, her brothers’.

In this way, Highsmith indicates her attitude towards life’s tragedies: pain and suffering are unjustified, and there is no answer to the purpose they serve. Bad things will inevitably happen to some people in certain moments. There is no reason behind it. That is the big, yet ugly, joke of life. She has embraced this joke, this absurdity, and incorporated it in her writing, much in the way Kafka did. Her tales are not cautionary.

This is not to say that her stories are simply sketchy portraits of women. They are, in fact, for all their brevity, perfectly self-contained narratives — more than mere glimpses or snippets of life histories. ‘The Mobile Bed-Object’ and ‘The Victim’ both trace the histories of their respective heroines from childhood to their finale (death for the former, a mysterious disappearance for the latter). Caricatures though these ladies may be – one being a dumb ‘bombshell’, the other a strangely enthusiastic ‘victim’ of sexual abuse – they are both fully visualised over just a few pages.

As well as the ‘bimbo’ and the ‘victim’, Little Tales of Misogyny features several other common stereotypes of women, including the neurotic, the housewife and the femme fatale. In the very brief stories, these women are destroyed by themselves and by others, through irony, dark humour and absurd situations. However, Highsmith’s women are not just passive recipients of violence; they can also be active agents of destruction. The femme fatale in ‘The Coquette’ is a perfect example. She ‘won the new suitor’s allegiance by promising to marry him, if he eliminated Bertrand’. Similarly destructive is the triumphant passive-aggressive behaviour of Elaine in ‘The Breeder’. Despite always insisting she is ‘on the pill’, Elaine gets pregnant numerous times, and ultimately pushes her husband towards a nervous breakdown.

Destructive behaviour is perhaps what Highsmith had in mind when writing the collection, and it may also be what has prompted the frequent charges against her perceived misogyny. Do I find her sometimes scathing portraits of female characters symptomatic of a general aversion towards women? No. There isn’t enough solid evidence of it in her work. Instead, what I detect is a satirical testament to what Highsmith considered some of the dysfunctions of the female mindset – and they aren’t  the self-generated traits of women. In each of the stories, whether subtly or explicitly, Highsmith exposes the social and familial influences on women. The underlying social mechanisms of patriarchy are visible for those keen enough to detect them here.

the self-generated traits of women. In each of the stories, whether subtly or explicitly, Highsmith exposes the social and familial influences on women. The underlying social mechanisms of patriarchy are visible for those keen enough to detect them here.

However, it isn’t the patriarchal displays that draw me to Highsmith — far from it — for remember, she remains ironically detached while recounting the various travails and misadventures of her characters. It is rather her fine sense of humour, her sense of rhythm, and the force of her writing style that interest me. It is the way her words seem to clash against each other as she enacts jarring, harsh transitions in unpredictable ways.

The introductory sentence of ‘The Hand’, the story that opens the collection, illustrates the aspect of unpredictability that enlivens all her stories: ‘A young man asked a father for his daughter’s hand, and received it in a box – her left hand’. Here, Highsmith takes a metaphorical expression and subverts it in a literal, brutal and playfully macabre way.

I have been drawn to dark stories about people with dark psyches since I can remember. Destruction seems an inevitable motif in literature and invariably manifests in a diptych: destroying others and destroying oneself. Highsmith’s books are rife with women who do not always appear to be outsiders, even if they are inwardly strange, sometimes twisted, and sometimes disaffected souls. Breakdown – be it a breakdown of nerves, language or otherwise – is an exit out of the absurd uniformity and sleekness of ‘normal’ life. Highsmith is, for me, one of those kindred souls: her magic hat is full of tricks in which reality as we know it disappears and then reappears, taking us by surprise.

Thanks for this, a selection from this book was published as part of the the Penguin ’60’ series– which where very short and small books carrying only one or two stories or a short novel extract. This was about 20 years ago and I remember being amused by what I read but there wasn’t enough to form a stronger opinion.

Your review of the whole collection makes me want to go back and read it. Also I enjoyed your analysis and the skillful way you write, in lines such as “She willfully abandons any sense of hope, reason and order, and almost aloofly casts off her heroines in cruel and irrational scenarios…”

I think the late Patricia Highsmith would not have been allowed– or would have been dissuaded– from using that title now. I’m certain it’s an ironic title, but people are these days more likely to take offence and not consider such a title might be ironically meant — or perhaps not care if it was, given the strange pleasure that some seem to find in taking offence at things, especially on social media. In fact, I’m sure Highsmith would’ve enjoyed writing a story about that kind of character. Anyway,. thanks for your article, it was a pleasure to read.