photo by Kriss Szkurlatowski

by Emily Cleaver

The short stories of Jorge Luis Borges are like beautiful, intricate puzzle boxes. They demand picking up, fiddling with, worrying over; their parts shift and interlock, revealing strange and unexpected secrets. ‘Death and the Compass’ is my favourite of Borges’ works. A policeman, Inspector Lönnrot, investigates the stabbing of a Jewish academic in a Paris hotel, the first in a series of murders that seem to be linked to a cabalistic ritual. It’s a detective story where a murder investigation becomes an existential quest.

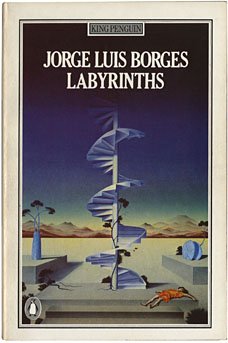

A prolific and hugely influential writer, Borges never wrote anything much longer than a few pages, but he dealt with big ideas in small spaces. ‘Death and the Compass’ is part of the collection Labyrinths, first published in 1962, in which all the stories explore the theme of the maze in some way. Here, we are in a maze of meanings. The story is full of signs and symbols, innuendos and false leads. Nothing is straightforward – even Lönnrot’s solution to the mystery turns out to be unreliable.

Thank you for the equilateral triangle you send me last night. It has

enabled me to solve the problem. This Friday, the criminals will be in

jail, we may rest assured.

I love detective fiction and have been known to devour an Agatha Christie in a single sitting, but I also love writing that plays with the structures and conventions of the genre, undermining them and building something more interesting. There’s a language of detective fiction that we all speak and understand without thinking about it: death anatomized, clues read, the guilty party identified. ‘Death and the Compass’ uses this morphology to examine a philosophical mystery. The solution isn’t as simple as Miss Marple pointing a finger at the culprit – we’re left troubled by a deeper and more fundamental puzzle that can’t be solved at all.

I love detective fiction and have been known to devour an Agatha Christie in a single sitting, but I also love writing that plays with the structures and conventions of the genre, undermining them and building something more interesting. There’s a language of detective fiction that we all speak and understand without thinking about it: death anatomized, clues read, the guilty party identified. ‘Death and the Compass’ uses this morphology to examine a philosophical mystery. The solution isn’t as simple as Miss Marple pointing a finger at the culprit – we’re left troubled by a deeper and more fundamental puzzle that can’t be solved at all.

It was already night; from the dusty garden arose the useless cry of a

bird. For the last time, Lönnrot considered the problem of symmetrical

and periodic death.

For Lönnrot, the search for the culprit is also a search for a secret – the name of God, which has the power to unlock knowledge of all things in the universe. The facts of the case, ‘mere circumstances, reality’, are irrelevant to him. A straightforward solution, of a theft gone wrong, is ‘possible, but not interesting’. Instead, he embarks on an investigation of knowledge itself. But the danger is that he’s reading too much into things – seeing patterns where there are none, or misunderstanding what he sees. ‘Lönnrot thought of himself as a pure thinker, an Auguste Dupin, but there was something of the adventurer in him, and even of the gamester.’ The great secret at the centre of this labyrinth may well be that there is no secret at all, that the maze is meaningless.

For the modern reader, ‘Death and the Compass’ rings all sorts of bells. We live in an age of conspiracy theories, desperate for things to be more than they seem, looking for and invariably finding sinister patterns in everything from the Jack the Ripper murders to 9/11. Lönnrot’s search is echoed everywhere today on conspiracy blogs and message boards.

The story’s influence, and that of others by Borges, can be traced in the works of writers and artists from Stanley Kubrick to Thomas Pynchon, Umberto Ecco to Dan Brown, who have all echoed its fascination with secret societies, hidden codes and patterns in world events.

The story’s influence, and that of others by Borges, can be traced in the works of writers and artists from Stanley Kubrick to Thomas Pynchon, Umberto Ecco to Dan Brown, who have all echoed its fascination with secret societies, hidden codes and patterns in world events.

Writers and readers of genre fiction, myself included, are often forced to defend their tastes against the charge of not being ‘real’ literature. Detective fiction, science fiction and fantasy are all looked down on by large parts of the literary establishment as not serious enough. But Borges saw the fantastic and bizarre as the most effective subjects through which to examine our existence. His stories are populated by a wild cast of brigands, adventurers and detectives, set in impossible libraries, alien ruins and multi-dimensional gardens, but they still manage to explore deep philosophical themes. As Professor Efrain Kristal has said, Borges makes us as readers “consider the possibility that the impossible and even the preposterous, can sometimes be more compelling than the real.”

His work always reassures me that writing about the fantastical and the strange is a legitimate literary approach. His confident and playful mixing of fact and fiction, truth and fantasy, feels dangerous, transgressive and cheeky. He shifts the sands under us – is this real or fake? Are we in on the joke or the subject of it? Every time I revisit his work, I’m inspired to try and write beyond my comfort zone.