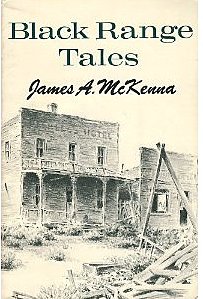

James A. McKenna’s Black Range Tales: Chronicling Sixty Years of Life and Adventure in the Southwest is a collection of sixteen stories recounting the adventures of a late nineteenth-century pioneer and prospector. Born in 1851, “Uncle Jimmie” McKenna left his home in Pennsylvania as a young man and worked his way to New Mexico’s Black Range Mountains, in search of a lot of adventure and a little bit of money. The stories were written down by McKenna and W. J. “Oxy Bill” Hamlett in Hamlett’s blacksmith shop (motto: we weld everything but a broken heart and the break of day!) and typed up by Sister Foley at the Holy Cross Sanatorium where McKenna resided for some time before his death at the age of 90. The collection was first published in 1936 and was republished by New Mexico’s Rio Grande Press in 1963 and 1991. Black Range Tales recounts McKenna’s adventures with humor and hope, and paints a vivid picture of a people who embodied the measured optimism of the American West.

Pioneers and prospectors of the nineteenth century traveled west without knowing much about the land they would encounter or how to mine it, but they went armed with the belief that they could learn. Both the environment and its people presented a great deal of danger to the pioneers; thus, a certain amount of optimism and stoicism was necessary for survival. They had to “face all kinds of danger from Indians, wild beasts, horse thieves, and outlaws” and “put up with a bleak and desolate country, a land of deserts,” without much food or water (McKenna 11). While the West held many dangers, though, these dangers were not often present at the same time and pioneers had to assess the level of threat in order to use their limited resources effectively, optimizing their likelihood of survival. For example, in ‘Pioneering from 1877 to 1887,’ McKenna travels with a Californian named Martin who had spent twenty years in the West. McKenna is worried because they only have one secondhand shotgun for protection but Martin disagrees: “I’ve gone from the Pacific to the Rockies and from the Arctic to Mexico without ever needin’ a gun. It’s a damn sight better to keep our money for feed and grub” (McKenna 6). Martin’s experience tells him that it is a wiser decision to use their limited funds on supplies because where they are going the environment is more dangerous than wild animals and Native Americans.

In addition to measured optimism, pioneers also had to have the ability to enter and exit business dealings easily in order to succeed. Business in the nineteenth century in New Mexico and the rest of the West had a low barrier of entry. Mines and claims changed hands quickly and the likelihood of failure was high. As a result, business dealings were risky. Doing business with many partners, or diversifying their portfolio of contacts, was one way that pioneers, including McKenna, minimized this risk. In ‘Pioneering from 1877 to 1887,’ McKenna points out that “myself and three other men who were footloose and without families pitched in together and hired a bull team” (1). After reaching Elizabeth Town, fifteen days later, McKenna quickly finds another partner, a man who needs someone to do the shoveling. “I agreed to take an interest in his diggings, promising to pay him twenty five dollars from the dust we took” (2). Another way of minimizing risk was to have a system of evaluating potential business partners. Though this system was clearly informal, pioneers had to draw conclusions from minimal interactions before upgrading potential business partners to actual business partners. Bad decisions would make the already risky business of mining even more uncertain and McKenna’s ability to choose (mostly) good partners indicates he has a good internal system for evaluating people.

Pioneers also made decisions about potential partners based on reputation. For example, “Pioneers had plenty of coin in those days, and a more honest group of men never lived. The merchant knew their word was as good as gold” (McKenna 12). At that time, the legal system in the American West was quite informal and breaches of contract could not always be litigated in a court of law. As a result, contracts were verbal rather than written and they were sealed with a handshake rather than a signature. It is not that a man’s word means less, today, but rather that, back then, a man’s word meant almost everything. A business arrangement was sealed with a handshake and reinforced with reputation. As a result, a man’s image in the community, his reputation, was worth more than individual business deals. A man’s reputation was his livelihood and a good reputation represented the ability to get future work.

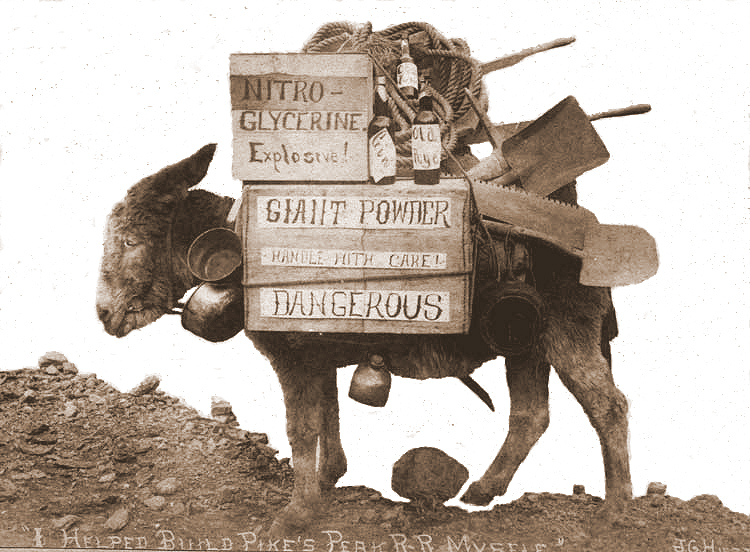

Another important characteristic of nineteenth-century pioneers is their almost constant interaction with animals. Unlike contemporary people, whose contact with animals tends to be limited to their pets, people of New Mexico and the rest of the West dealt with animals in a variety of ways. For example, they used mules, burros and horses for transportation, they hunted deer and rabbits for food, they killed bears out of fear and sometimes for their pelts, and they kept dogs and occasionally skunks as pets.

The different interactions that pioneers had with different animals are similar in structure to the interactions they had with different types of people. For example, pioneers did not treat the domesticated animals they used for transportation or food as pets. This kind of compartmentalization was necessary because many burros and horses were worked to death and their deaths could not be taken personally: “Our pinto horse was virtually played out, so we made up our minds to rest up for a few days and try to trade him off” (McKenna 8). The relationship between a pioneer and his work animal was a lot like his relationship with a distant business partner. He benefited from his connection to the business partner and laughed at the comical situations the partner presented. For example, McKenna notes a peculiarity of burros and mules: “No matter how deep or swift the stream, they nearly always stopped to void right in the middle of it, and all hell could not move them until they got ready to push on” (7). But the pioneer was not friends with either his mule or his distant business partner. As a result, when one or the other died or moved on, he was not devastated by the loss and quickly found a replacement.

Unlike his relationship with domesticated livestock, the pioneer’s relationship with wild animals such as bears was rooted in fear, and many bears were consequently killed. McKenna’s own attitude towards bears, however, is more complex than that. On one occasion, he appears to view bears with great empathy and respect, stating that “a few silvertips still live in the Gila forest, but they have learned to fear the guns of the white man, and they find themselves dens far out of his reach. The silvertip has been almost wiped out, and where he does live in small numbers, as in the Gila Forest, his power is broken” (25). However, on another occasion, he and a friend kill a grizzly, make a business deal with two miners from Pinos Altos, and profit off the hunt: “They finally got us to go back for the pelt of the silvertip, promising to pay as well for trouble, though we told them the pelt was worthless. The head was what they wanted” (27). Therefore, it is clear that McKenna’s ability to empathize with bears and their uncertain future in the ecosystem does not interfere with his ability to function according to his society’s rules or his profit motives. Finally, when two orphan cubs run up to his cabin and he cares for them as his pets, McKenna is involved in yet another kind of relationship with bears. “I was kept busy catching fish, hunting deer, and gathering berries, and tender twigs and grasses” (McKenna 28). By caring for them, McKenna forms a very close bond and starts to sound like a proud parent, creating some of the most memorable passages in the narrative. “They grew fast and were tame and smart. Both learned to dance and to wrestle with me” (McKenna 28). Later, McKenna feels a great sense of remorse for accidentally killing one of the cubs and for giving the other one to a circus: “I missed him more than any pet I ever had” (29). McKenna’s relationship with bears is full of complexity and contradiction, and it is likely that other pioneers felt the same way. He hunts the ones that antagonize or scare him and adopts the ones that need him. He appears concerned about the state of nature and the diminishing number of bears and laments that he did not practice conservation in his deer hunting.

Unlike his relationship with domesticated livestock, the pioneer’s relationship with wild animals such as bears was rooted in fear, and many bears were consequently killed. McKenna’s own attitude towards bears, however, is more complex than that. On one occasion, he appears to view bears with great empathy and respect, stating that “a few silvertips still live in the Gila forest, but they have learned to fear the guns of the white man, and they find themselves dens far out of his reach. The silvertip has been almost wiped out, and where he does live in small numbers, as in the Gila Forest, his power is broken” (25). However, on another occasion, he and a friend kill a grizzly, make a business deal with two miners from Pinos Altos, and profit off the hunt: “They finally got us to go back for the pelt of the silvertip, promising to pay as well for trouble, though we told them the pelt was worthless. The head was what they wanted” (27). Therefore, it is clear that McKenna’s ability to empathize with bears and their uncertain future in the ecosystem does not interfere with his ability to function according to his society’s rules or his profit motives. Finally, when two orphan cubs run up to his cabin and he cares for them as his pets, McKenna is involved in yet another kind of relationship with bears. “I was kept busy catching fish, hunting deer, and gathering berries, and tender twigs and grasses” (McKenna 28). By caring for them, McKenna forms a very close bond and starts to sound like a proud parent, creating some of the most memorable passages in the narrative. “They grew fast and were tame and smart. Both learned to dance and to wrestle with me” (McKenna 28). Later, McKenna feels a great sense of remorse for accidentally killing one of the cubs and for giving the other one to a circus: “I missed him more than any pet I ever had” (29). McKenna’s relationship with bears is full of complexity and contradiction, and it is likely that other pioneers felt the same way. He hunts the ones that antagonize or scare him and adopts the ones that need him. He appears concerned about the state of nature and the diminishing number of bears and laments that he did not practice conservation in his deer hunting.

Black Range Tales is a well-written first-person narrative of life in the American West. It is filled with stories which not only show the hardship of pioneering life but also the fun, humor and excitement that life involved, and convey the spirit of adventure and optimism of men who were driven West by “something bigger than gold” (McKenna 13). The tales also shed light on the relationship between civilization and nature, and how the pioneers rid the West of wild animals and wild people in order to make the region safe for white Western society. The irony is that a boring life in a safe and habitable environment was exactly the kind of life those early pioneers and prospectors were trying to get away from when they left their homes back East.