photo by anon

by Jose Varghese

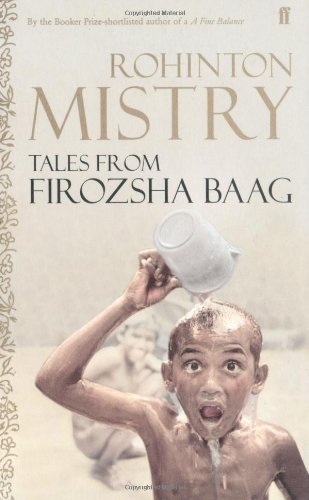

Rohinton Mistry is a Parsi writer who has written extensively about India and the Parsi community in almost all his literary works. He is the author of Tales From Firozsha Baag, a collection of short stories, and three novels – Such A Long Journey, A Fine Balance and Family Matters. Apart from A Fine Balance (in which Mistry deals with Indian characters from all walks of life), all his works have Parsis as main characters. The way in which the Parsis lead their life in India and abroad takes precedence over the pan-Indian experience that many contemporary Indian writers aim to depict. In Tales From Firozsha Baag, a metafictional reference to the role of creativity in relation to the Parsi existence in India is used in order to make clear the author’s views on the process of writing about an ethnic minority in combat zones. Firozsha Baag, the modest Parsi apartment building in Mumbai, maintains its central position in the narrative since all the stories are in some way or the other connected to it.

‘Squatter’ is a story from the collection that deals with cultural collisions in a humorous way. Its scatological references are intricately related to the plight of a Parsi immigrant in Canada, for whom the frequent necessity to invent imaginary homelands becomes a ‘pain in the posterior’. It is an immensely engaging story in which issues related to immigration are presented in a very humorous but matter-of-fact manner.

‘Squatter’ is a story from the collection that deals with cultural collisions in a humorous way. Its scatological references are intricately related to the plight of a Parsi immigrant in Canada, for whom the frequent necessity to invent imaginary homelands becomes a ‘pain in the posterior’. It is an immensely engaging story in which issues related to immigration are presented in a very humorous but matter-of-fact manner.

The narrator is Nariman Hansotia, who engages the kids of Firozsha Baag with his interesting stories. His story uses the oral narrative pattern that has been adopted by writers like Salman Rushdie – both as an Indian storytelling device and also as a postmodernist narrative technique. Hansotia’s narrative starts with the story of the valorous Savushka who has an amazing talent as a cricket player and as a hunter, but he fails to succeed in either field as he does not dedicate his life to a single cause.

The storytelling then shifts to the experiences of Sarosh, who migrates to Canada because of the open hostility towards Parsis by fundamentalist outfits in the post-independence India. Like any other Parsi from India, the necessity for Sarosh to construct a homeland for himself amidst transnational spaces makes him go through immigration hardships with dignity.

However, there is something unique about Sarosh’s predicament. Before migrating to Canada, he declared that he would come back to India if he failed to become a true Canadian in every way within ten years’ time. The one thing that makes him feel that he is not yet an authentic Canadian is that he fails to use the water closet. He can empty his bowel only in the squatting position. In a sarcastic tone, the narrator elaborates on how Sarosh develops some sort of a neurosis.

In his own apartment Sarosh squatted barefoot. Elsewhere, if he had to go

with his shoes on, he would carefully cover the seat with toilet paper before

climbing up […] And if the one outside could receive the fetor of Sarosh’s

business wafting through the door, poor unhappy Sarosh too could detect

something malodorous in the air: the presence of xenophobia and hostility.

In his desperate attempt to fulfill his own criteria, Sarosh spends more and more time in the toilet trying to master the Western way of emptying one’s bowels:

Each morning he seated himself to push and grunt, grunt and push,

squirming and writhing unavailingly on the white plastic oval. Exhausted,

he then hopped up, expert at balancing now, and completed the movement

quite effortlessly.

As the ten year deadline comes close, he even approaches the Immigrant Aid Society, but none of their outrageous suggestions or so-called technological devices like ‘Crappus Non Interruptus or CNI’ can help him. In the meantime, he is fired by his Boss for keeping irregular hours at the office, thanks to his frequent visits to the toilet. Sarosh decides to go back to India.

Finally, once he is on his flight to India, he manages to perform in the toilet the Western way, as the plane takes off. But he still chooses to return to India. He is presented, in the end, as a person disillusioned by all his endeavours to negotiate cultural collisions in life. Just like a Shakesperian tragic hero, this protagonist of Mistry’s tragicomedy says:

Tell them that the world can be a bewildering place, and dreams and

ambitions are often paths to the most pernicious traps…I pray you in

your stories, when you shall these unlucky deeds relate, speak of me as

I am; nothing extenuate, not set down aught in malice; tell them that

in Toronto once there lived a Parsi boy as best as he could. Set you

down this; and say, besides, that for some it was good and for some it

was bad, but for me life in the land of milk and honey was just a pain in

the posterior.

Apart from being among the Indian diaspora writers, Mistry is a representative of the Parsi diaspora too. While the cultural conflicts in Canada and other non-Indian locales brings him back to the imaginary homeland of India, the way in which the Parsis confront other sorts of cultural conflicts in India has to direct him to the fastidious preservation of the Zoroastrian faith.

Apart from being among the Indian diaspora writers, Mistry is a representative of the Parsi diaspora too. While the cultural conflicts in Canada and other non-Indian locales brings him back to the imaginary homeland of India, the way in which the Parsis confront other sorts of cultural conflicts in India has to direct him to the fastidious preservation of the Zoroastrian faith.

For most diasporic communities, the urge to go back to their homeland is what makes their life worth living. But quite paradoxically, the original homeland of the Parsis is lost forever. For the Parsis, returning to Iran is an improbability, since their religion has not survived the Muslim attacks there, and it has become an Islam dominated area where there is little scope for building up a home of their dreams. Unlike the Jews, who always nourish the dream of homecoming, the Parsis are destined to create their own homelands. It is a strange but comprehensible fact that Parsis look at India as their homeland. It was the place that gave them refuge in their aimless exodus. The plight of Sarosh in ‘Squatter’ becomes all the more significant in this context, because he comes back to India, which is home for him more as a cultural construct than an ethnic, geographical reality.

* The Parsis are the people who followed the Zoroastrian faith in Iran and were forced into exile by the Islamic conquest of Iran. This makes them a diaspora in India itself. They are the successors of the minority of Zoroastrians who rebelled against the Arabs – refusing to be adapted to their religion and customs – following repeated attacks on the Persian Empire between 638A.D. and 641 A.D. *

Thanks Mel, I am glad you liked the post. And, ‘A Fine Balance’ is a must read.

Great post. I have read all his novels but A Fine Balance.