photo by Olga Pérez

by Wanda Campbell

~

You’re quite sure you won’t forget to write that story for me?

…Make it extremely squalid and moving.

~

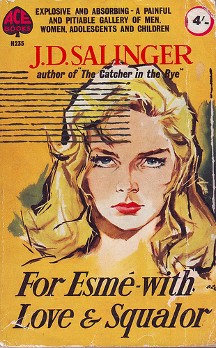

When I read ‘For Esmé–With Love and Squalor’, which first appeared in The New Yorker in 1950 and later in Nine Stories (1953), I did not know it was considered one of J.D. Salinger’s best stories, but I knew that I liked it. I have since read critics who call it ‘the high point’ of his art and a ‘minor masterpiece’ and I have come to understand why. Through a successful combination of character, caring, and content drawn from life, or, as Paul Alexander put it, ‘an ideal fusion of innovative narrative technique and provocative subject matter’, Salinger has transformed details of his life into art.

Though Salinger was one of the most reclusive and private authors of the twentieth century, we know something of the life that informed this story. We know that Salinger was drafted into the U.S. Army in 1942, spent time in England training for the D-Day invasion, and landed on Utah Beach on June 6, 1944. He saw combat in many battles including the Hürtgen Forest Campaign and the Battle of the Bulge. As a counter-intelligence officer, he was one of the first to enter a liberated concentration camp and was hospitalized for ‘battle fatigue’ in Germany. Strategies for surviving such darkness appear in Salinger’s unforgettable story, the title of which is especially compelling because it encapsulates the key elements the story contains, and the key lessons it has to teach.

For Esmé

I told her that I’d never written a story for anybody,

but that it seemed like exactly the right time to get down to it.

Stories are for people. Esmé asks for a story and the American soldier does his best to comply with her request. The short story has been described by Tillie Olson as ‘a healing riddle’, and ‘a form of prayer’ by John Berger, but stories are first and foremost gifts from one human being to another. I believe that bit that appears at the beginning of novels and films – any resemblance to actual persons living or dead is purely coincidental – was written by lawyers not authors. Salinger’s daughter, Margaret, describes how one biographer went ‘all over that part of England posting notices in local papers in search of the “real” Esmé’, and concludes ‘that sort of thing leaves [her] cold’ – perhaps because it undermines her father’s great skill in the creation of character. I don’t know if Esmé was based on a real person, but she was so vividly portrayed in this story that she lives on with her insightful courage, marvellous vocabulary and her ‘oddly radiant’ smile. In fact, she was so real and so appealing that I named my daughter after her.

Stories are for people. Esmé asks for a story and the American soldier does his best to comply with her request. The short story has been described by Tillie Olson as ‘a healing riddle’, and ‘a form of prayer’ by John Berger, but stories are first and foremost gifts from one human being to another. I believe that bit that appears at the beginning of novels and films – any resemblance to actual persons living or dead is purely coincidental – was written by lawyers not authors. Salinger’s daughter, Margaret, describes how one biographer went ‘all over that part of England posting notices in local papers in search of the “real” Esmé’, and concludes ‘that sort of thing leaves [her] cold’ – perhaps because it undermines her father’s great skill in the creation of character. I don’t know if Esmé was based on a real person, but she was so vividly portrayed in this story that she lives on with her insightful courage, marvellous vocabulary and her ‘oddly radiant’ smile. In fact, she was so real and so appealing that I named my daughter after her.

Of course, the story is populated with lots of other vivid characters, including Charles with his riddles and Bronx cheers, Clay, more prepared for combat than for life, and Sergeant X who most resembles Salinger himself. Authors, however successfully disguised, always find their way into stories. In this case, X is the sign of his presence when his own signature, like the quotation from Dostoevsky, is unintelligible. X marks the spot of the true treasure, the making mind. Characters are made of multitudes, but mysteriously, miraculously, they become themselves. This is what makes them worthy of the writer’s skill and the reader’s respect.

With Love

“Fathers and teachers, I ponder ‘What is hell?’ I maintain that it is the suffering of being unable to love.” He started to write Dostoevsky’s name under the inscription, but saw… that what he had written was almost entirely illegible.

Salinger extends love to his characters, and the characters within Salinger’s story extend healing gestures to each other. Even the soldiers, who ‘act like animals’, are treated with compassion because they are a long way from home and ‘few of them had had any real advantages in life’. If the story-teller doesn’t care for the characters or the story why should the reader? The story-teller must enter into the experience of the character with love but not sentimentality, and the best way to reveal the former and combat the latter is through craft. Salinger’s craft appears in language that is symbolic, significant and sustaining. In ‘For Esmé—with Love and Squalor’, he proves himself to be a master of metaphor. Two of my favourite examples are the description of a man ‘like a Christmas tree whose lights, wired in series, must all go out if even one bulb is defective’ and the moment when Sergeant X feels his mind “dislodge itself and teeter, like insecure luggage on an overhead rack”. These similes are at once exact and surprising.

Salinger extends love to his characters, and the characters within Salinger’s story extend healing gestures to each other. Even the soldiers, who ‘act like animals’, are treated with compassion because they are a long way from home and ‘few of them had had any real advantages in life’. If the story-teller doesn’t care for the characters or the story why should the reader? The story-teller must enter into the experience of the character with love but not sentimentality, and the best way to reveal the former and combat the latter is through craft. Salinger’s craft appears in language that is symbolic, significant and sustaining. In ‘For Esmé—with Love and Squalor’, he proves himself to be a master of metaphor. Two of my favourite examples are the description of a man ‘like a Christmas tree whose lights, wired in series, must all go out if even one bulb is defective’ and the moment when Sergeant X feels his mind “dislodge itself and teeter, like insecure luggage on an overhead rack”. These similes are at once exact and surprising.

Symbolism is woven throughout the story from the names of the characters to mundane gestures that echo larger gestures, so that the soldier looking at the names of young choir members listed on the bulletin board resembles the act of looking at casualty lists. When Clay swears “Christ almighty”, the narrator says, “It meant nothing. It was Army”. In this context the words are not a prayer or an oath or even a curse but only emptiness. The words of the narrator, on the other hand, are heavy with significance even when they slip into sarcasm. And this is true of all of those who have suffered grief and come through to the far country, in contrast to those who just don’t have a clue, like the amateur psychologist Loretta or the older brother in Albany with his request to send ‘the kids a couple of bayonets or swastikas’. There are those who throw away language, but there are those who hang on to communication between human beings as the one true thing.

Esmé’s practice of spelling words to protect the innocent becomes another kind of spell, the kind of magic that combats mortality. She saves her father’s letters so that even when the man himself is buried in the earth, his words continue, as does his belief that humour equips you for life. Gifts of language and laughter are among our most powerful weapons against despair.

Even if we acknowledge that significance is a slippery notion, it is still something that we long for, that satisfies us when we find it. Fiction reveals that the human mind is an astonishing instrument capable of all kinds of extrapolation, so a fictional country does not have to resemble the one we inhabit to show us how we might better live in it. According to Margaret Atwood: ‘Writing is what we choose to say to one another. It can be a prayer or a curse; it can be our anger, but it can also be our love. It can keep on speaking to others, even after we die’.

And Squalor

“Are you at all acquainted with squalor?”

I said not exactly but that I was getting better acquainted with it,

in one form or another, all the time.

Set as it is in the closing days of World War II, this story has no trouble at all in answering Esmé’s request for squalor. This was Die Zeit Ohne Beispiel (‘The Time Without Parallel’ or ‘The Unprecedented Era’), if we take the word of Joseph Goebbels, the Nazi mastermind who was sickened by human beings. But Salinger knew that there have been many times in history when human beings have entered hell because they were unable to love. This story doesn’t leave squalor out there as some external menace but reveals how it enters into Clay’s trigger hand when he shoots the cat, or the hand of Sergeant X that shakes so badly that he can barely read what he himself has written. This time of driving ‘combat-style with the windshield down on the hood’ was not one that brought out the best in people, but Esmé has asked for a story that was both squalid and moving. And this story does move from darkness to a tentative light.

Set as it is in the closing days of World War II, this story has no trouble at all in answering Esmé’s request for squalor. This was Die Zeit Ohne Beispiel (‘The Time Without Parallel’ or ‘The Unprecedented Era’), if we take the word of Joseph Goebbels, the Nazi mastermind who was sickened by human beings. But Salinger knew that there have been many times in history when human beings have entered hell because they were unable to love. This story doesn’t leave squalor out there as some external menace but reveals how it enters into Clay’s trigger hand when he shoots the cat, or the hand of Sergeant X that shakes so badly that he can barely read what he himself has written. This time of driving ‘combat-style with the windshield down on the hood’ was not one that brought out the best in people, but Esmé has asked for a story that was both squalid and moving. And this story does move from darkness to a tentative light.

The package that Esmé sends, and which the Sergeant opens as if it were a stick of dynamite, ‘watching the string burn all the way down’, in fact diffuses the distress within his f-a-c-u-l-t-i-e-s, so that he can enter a healing sleep. The watch crystal which might allow him to see into the future is broken, and he is not even sure whether it works, but the mere presence of Esmé’s generosity – in sending this ‘shock-proof’ talisman that belonged to her father who was s-l-a-i-n, as well the repeated HELLO of the little brother – is enough to begin the restoration. We know this because the story begins in that future in which the narrator is restored to the first person – still alive, still married, still writing, still eager to pass on the lessons he has learned.

In his essay, ‘Lost off Cape Wrath’, John Berger writes, ‘Authenticity in literature does not come from the writer’s personal honesty. Authenticity comes from a single faithfulness; that to the ambiguity of experience’. The very act of writing is an antidote to whatever dis-ease the world offers. To paraphrase Lord Acton, art heals and absolute art heals absolutely. The qualities that give stories their power include character, caring, and content authentically rendered – reaching across time and space with love and squalor. Tim O’Brien says it comes down to gut instinct: ‘A true war story, if truly told, makes the stomach believe’. Stories matter because they have been chosen, rescued, and revived. They have been pulled dripping and breathless from the often overwhelming waves of human experience. We all come into the world with the desire to tell stories, yet many of us forget how along the way. Remembering is necessary to our survival. In her book, Living by Fiction, Dillard describes an ‘insane notion’ that she believes to be true.

Physical things are falling apart at a terrific rate; people, on the other

hand, put things together. People build bridges and cities and roads;

they write music and novels and constitutions; they have ideas. That

is why people are here; the universe as it were needs somebody or

something to keep it from falling apart.

By telling stories we do our part to keep the universe from falling to pieces. By telling stories we do our part to keep our f-a-c-u-l-t-i-e-s intact. When the narrator of Salinger’s story throws his gasmask out the porthole of the Mauretania, in order to fill the container full of books, it is the action of a man who knows where his best chances for survival lie. Words out of the darkness into the light.

~

Wanda Campbell teaches Creative Writing and Women’s Literature at Acadia University, in Wolfville Nova Scotia, Canada. She has published an anthology of early Canadian women poets, texts for Penguin, four poetry collections (Daedalus Had a Daughter, Grace, Looking for Lucy, and Sky Fishing), in addition to numerous academic and creative journal publications and a forthcoming novel.

Wanda Campbell teaches Creative Writing and Women’s Literature at Acadia University, in Wolfville Nova Scotia, Canada. She has published an anthology of early Canadian women poets, texts for Penguin, four poetry collections (Daedalus Had a Daughter, Grace, Looking for Lucy, and Sky Fishing), in addition to numerous academic and creative journal publications and a forthcoming novel.