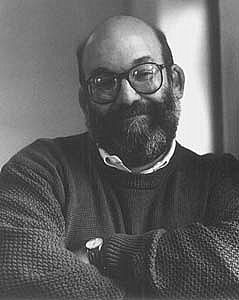

photo by Michael Gross

by Sarah Hegarty

I discovered Frederick Busch’s short story ‘Ralph the Duck’ in a writing textbook when I was a student. At the time, I was stunned by its emotional power, and I remember how, from the title to the very last line, Busch conveyed with humour, and sometimes with unbearable poignancy, the essence of family life. In elegant, deceptively simple prose, he laid bare the rawness of a couple’s pain as they grieved for their dead daughter. It was one of those stories that stayed with me.

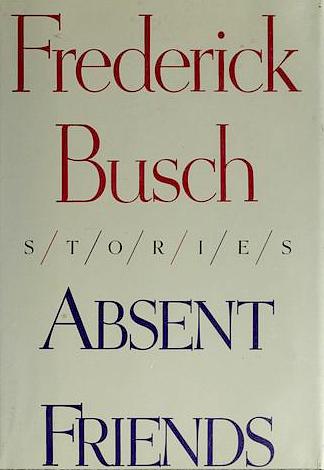

Two years ago, in a second-hand bookshop in Washington DC, I found a collection of Busch’s short stories, Absent Friends. My heart beat faster as I held the book in my hands and scanned the contents page for ‘Ralph the Duck’. There it was. Page 66. When I returned across the Atlantic, I brought my own copy back with me.

Busch was born in Brooklyn in 1941, and from 1966 to 2003, he was first Professor and then Professor Emeritus of Literature at Colgate University in Hamilton, New York. He won the American Academy of Arts and Letters Fiction Award in 1986, and the PEN/Malamud Award in 1991. Altogether, he published seventeen novels and four collections of short stories. He died of a heart attack in February 2006, only a couple of years into his retirement. He was sixty-four.

‘Ralph the Duck’ is told by an unnamed narrator, employed as a caretaker/ security guard at a college in the north-eastern US – territory that Busch made his home in fiction, as well as in real life. At night, the narrator patrols the campus ‘in a Bronco with a leaky exhaust system’, turning off lights and taps; breaking up fights; rescuing drivers with flat tyres or flat batteries.

Because he’s on the staff, he can take a free course each term: he is ‘getting educated, in a kind of slow-motion way.’ His relationship with the faculty is beautifully drawn. ‘You are not an unintelligent writer,’ says his professor, ‘a tall, handsome guy who never wore a suit’ and has an eye for the prettiest girls. Meeting one night when the professor’s Buick has a flat battery, the prof looks him over ‘the way men sometimes do with other men who fix their cars for them’ and poses a one-word question: ‘Vietnam?’ The narrator is clear: ‘Slick characters like my professor like it if you’re a killer or at least a onetime middleweight fighter.’ He resists the conversation, and just smiles ‘like I knew something’. Back in his car, the professor flashes his headlights in farewell. ‘You are not an unintelligent driver,’ says the narrator.

His relationship with his wife, Fanny, is under strain. When the story opens, early on a winter morning, she’s asleep on the sofa downstairs. The narrator, having dealt with their vomiting dog, tiptoes past his wife. He’s convinced that he hears her blink, as he always can ‘after I’ve made her weep’. Busch shows us the reality of two broken people, trying not to break their marriage: when Fanny wakes, the narrator knows he’ll apologise, ‘because I always did, and then she would forgive me if I hadn’t been too awful – I didn’t think I’d been that bad – and we would stagger through the day, exhausted but pretty sure we were all right.’

The voice is factual, the language straightforward. But the reader has to pay attention: this narrator doesn’t waste words. And despite his undemonstrative exterior, his grief is never far away. Sitting alone in his house, watching the snowy sky, he remembers the student he found, standing outside in the cold, crying. He had persuaded her to go back indoors: ‘I thought of her as someone’s child,’ he says, adding, so quietly that we might miss it, ‘Which made me think of ours, of course.’ This is the first mention of their loss.

Busch conjures up a house that feels empty with two people in it. The couple’s terrible pain is almost palpable. Yet their life goes on, and they try to care for each other: when Fanny goes to work she leaves him food, which he shares with the dog; she lets him snore through a Japanese film and kisses him awake.

When the professor sets an assignment on Rhetoric and Persuasion, the narrator writes Ralph the Duck. The story is just a few lines, about a duckling with no wing feathers, whose mother keeps him warm ‘with her big feathery wings.’

By now our empathy for this character is such that we know this little tale must be significant. He wouldn’t waste our time with anything meaningless.

Perhaps it was a story he read to his daughter, with all the habit and ritual that implies; perhaps he made it up about one of her favourite toys: a talisman that comforted the parents as much as the child.

Or was the cold, shivering duckling his sick daughter? Unable to comfort her any other way, did her father take her into the world of his imagination, and try to show her that someone else – the baby duck – felt the way she did? Was that how he tried to make everything all right? By using the only powers we have to see the world differently: empathy, and imagination.

The narrator knows the professor won’t understand; he doesn’t care. He’s daring the man to see him for who he really is; trying to write about the most terrible thing that has happened to him, safe in the knowledge that the other man isn’t listening. He’s also signalling that he’s fed up with his fakery.

The professor gives him a D.

Despite the narrator’s bravado, the lack of empathy is too much. He goes home and calls in sick, which he’s never done. When his wife finds him she knows something’s wrong. ‘You’re familiar enough with Ds,’ she says. ‘I never saw you get this low over a grade.’

‘I wrote about Ralph the Duck,’ he says.

He doesn’t need to say more. She comes over and hugs him. Busch shows so eloquently the shorthand of their shared experience; a pain that can barely be expressed.

The rest of the story unfolds in a terrifying winter storm: ‘one of the worst in years.’ The college closes, and only the emergency operator and the narrator are working. Out in his truck, ‘the defroster set high, the little blue light winking’, he gets a call about a missing student, who has taken an overdose and wandered out into the freezing night.

At great risk to himself, he sets out after her in the truck, ‘bucking snow and sliding on ice, putting all the heater’s warmth up onto the windshield because I couldn’t see much more than swarming snow.’ His feet are still cold from helping a stranded driver. ‘I shivered, and I thought of Ralph the Duck.’

At great risk to himself, he sets out after her in the truck, ‘bucking snow and sliding on ice, putting all the heater’s warmth up onto the windshield because I couldn’t see much more than swarming snow.’ His feet are still cold from helping a stranded driver. ‘I shivered, and I thought of Ralph the Duck.’

He finds the girl in the quarry above the campus, in her nightdress: ‘she looked tiny against all the darkness.’ He wraps her in a blanket and gets her back to the truck, then sets off on the perilous journey to the hospital.

A trademark of Busch’s writing is the attention to detail of physical actions: to get down from the quarry, ‘I dropped the truck into four-wheel high. The cab smelt like burnt oil and hot metal.’ He careers around the campus, ‘on the edge of out-of-control, sensing the skids just before I slid into them.’ The pace picks up, the language reflecting urgency and speed: ‘We were past the chapel now, and the observatory, the president’s house, then the bookstore.’ We’re in the cab with him: talking to the emergency operator over the radio; talking to the girl, trying to keep her awake even though her face ‘looked all too blue through its whiteness.’ It’s then, rushing through this cold, dark night, that he tells her the thing he can’t talk about. ‘My wife, Fanny. She and I had a small girl one time.’

But of course the girl can’t hear. And he says, ‘Now, I do not want you dying.’ He can rescue this child – someone else’s daughter – but he couldn’t save his own. And he can only talk about what’s happened, reveal the truth, to someone who isn’t listening; who can’t hear him.

The death of children is a recurring theme in Busch’s work. A father himself, of two adult sons, one of whom served in Iraq, he nails the terror of parenthood: no amount of love can keep children safe. And the ferocity of a parent’s love for their child can put at risk, or destroy, the union that produced it. On the New York Times website, Booklist commented that, ‘Busch writes about the North American family with such depth of feeling and understanding that most of his stories are sad. If stories could be too poignant, these would be guilty.’

The ghost of the dead child haunts ‘Ralph the Duck’ as she haunts the characters’ marriage. Perhaps they feel they’ve exhausted the subject of their loss, but the story doesn’t feel like that: it feels like a huge, unexplored, inexpressible pain. As the narrator admits, when he puts up with the patronising air of the professor, ‘I did want to learn about expressing myself.’ The phrase hints at therapist-speak, and suggests time spent in counselling. Or perhaps Fanny has yelled that at him in frustration.

Busch returned to this character, later called Jack, in his novel Girls (1997), and its sequel, North (2005). He told interviewer Robert Birnbaum that he was drawn to Jack by the ‘hard-won simplicity of his language’, and because he ‘doesn’t have enough words.’ Talking about Jack in North, he said, ‘His language consistently fails him, and maybe it consistently fails all of us.’

Perhaps ‘Ralph the Duck’ is also about the power of story to give us language; to give us a narrative that shows us the best we can be: trying to make marriages work; coming to terms with unspeakable loss; putting ourselves in someone else’s shoes and in so doing, making ourselves a little more human.

We don’t discover whether the suicidal student lives; there’s no suggestion of another baby to ease the pain of this couple’s loss. Perhaps neither of them could risk such pain again. But Busch shows us that their love has survived.

At the end of the story, despite her anger that he risked his life to save someone else’s daughter, Fanny asks, ‘So tell me what you’ll tell a waiting world. How’d you talk her out?’ When he doesn’t answer directly she repeats, ‘What did you say?’

‘I told her stories,’ he says. ‘I did Rhetoric and Persuasion.’

This is obviously so far from her husband’s character that Fanny would have every right to be dumbstruck; or to make a cutting remark. But Busch has more faith in her. Without missing a beat she replies, ‘Then you go in early on Thursday… and you get that guy to jack up your grade.’

When I first read ‘Ralph the Duck’ I was starting out as a writer, searching for clues about how to do it. I still am. But I hope I’ve absorbed something of this story under my writing skin and kept faith with Frederick Busch. He’s the one who showed me so clearly how to pin emotion to the page with language that is stripped to the bone.

I think he’d be pleased. As he said to Robert Birnbaum, ‘I don’t feel I’ve earned the right to walk on the ground I walk upon, unless I’ve made good language: words that are useful to someone other than me.’

~

Sarah Hegarty was born in Bristol, and grew up in the north-west. After graduating in Modern Chinese Studies from Leeds University, she worked as a journalist, latterly freelancing for newspapers and magazines. She has an MA in Creative Writing from the University of Chichester. Her short fiction has been published in Mslexia, on the web (at www.exeterwriters.org.uk) and in the Momaya Annual Review. Her novel, The Ash Zone, won the 2011 Yeovil Literary Prize.

Sarah Hegarty was born in Bristol, and grew up in the north-west. After graduating in Modern Chinese Studies from Leeds University, she worked as a journalist, latterly freelancing for newspapers and magazines. She has an MA in Creative Writing from the University of Chichester. Her short fiction has been published in Mslexia, on the web (at www.exeterwriters.org.uk) and in the Momaya Annual Review. Her novel, The Ash Zone, won the 2011 Yeovil Literary Prize.

I agree, Dora: it’s just magical when a writer speaks to you. What I love about Frederick Busch’s writing is his humility – he doesn’t get in the way of his characters – and his affection for them, even when they do stupid things. I was so sad when I discovered, researching this piece, that he’d died – and at such a young age. ‘Ralph the Duck’ meant so much to me – still does – that I felt I wanted to tell him! So I’m really glad that I’ve had this opportunity to tell more people about his work. Thanks for your comment!

I feel like a kid in a candy store: so many wonderful writers for me to choose from, and each one speaks to me. Sarah, as you’ve described “Ralph the Duck,” it sounds like a story that I can learn from too. Like you, I was, and am, on the lookout for writers who have the same sensibility as I have, hoping that their success will show me the way to better writing. Now if I can only find the time to read them all.

Thanks Sarah!