photo crop © Tara R, 2011

*

We are delighted to announce the results of the 2016 THRESHOLDS International Short Fiction Feature Writing Competition…

~

OUR 2016 WINNER:

Alex Coulton with ‘The Iron Which Pierces the Heart’

~

Runners-up:

Mary O’Donnell with ‘An Epiphany in the Company of Alice Munro’

Tyler Miller with ‘The Radical Horror and Loneliness of The Martian Chronicles‘

Look out for the features from our runners-up on Thresholds next week.

~

Comments from the judging panel on Alex Coulton’s entry:

‘An immediately involving and powerful examination of Carver’s collection. Provocative, clear-eyed and unflinching in its analysis’; ‘the framework story of the reluctant pupil opens out a defence of the material in a lively and thoughtful way but without taking up too much room’; ‘there is a gripping, storytelling quality to this piece of writing … entertaining and insightful.’

~

Alex Coulton grew up in Herefordshire. She read English at Oxford, and then spent thirteen years teaching English in secondary schools. In 2014, whilst teaching at Highgate in north London, she completed the Master of Studies in Creative Writing at Oxford, before taking a sabbatical in Paris to complete her first full-length fiction manuscript. This project, now titled What We Found At The End won the Literature Works First Page Prize in 2015. Alex is represented by Sue Armstrong at Conville&Walsh.

Alex Coulton grew up in Herefordshire. She read English at Oxford, and then spent thirteen years teaching English in secondary schools. In 2014, whilst teaching at Highgate in north London, she completed the Master of Studies in Creative Writing at Oxford, before taking a sabbatical in Paris to complete her first full-length fiction manuscript. This project, now titled What We Found At The End won the Literature Works First Page Prize in 2015. Alex is represented by Sue Armstrong at Conville&Walsh.

~

The Iron Which Pierces The Heart

by Alex Coulton

It started with Sam James.

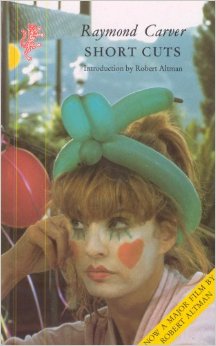

Sam James was the leader of the pack. On the surface, he was an unobtrusive boy whose only distinctive feature was his bright red hair. But when Sam James spoke, you knew. And so, when the sixth form decided to mutiny about studying Raymond Carver’s Short Cuts, it was inevitably Sam James who led the charge.

He came and leant against my classroom door one blustery afternoon in September. I was new to teaching then, and I suppose that sixth form class saw me as a sitting duck; thought they’d only have to put me in their sights and Sam James would shoot me down, in a flurry of squawks and feathers. Sam-the-man, Jamesy, the boy whose syrupy vowels had that same droit de seigneur he exhibited when he strolled across the pitches for a cigarette before prep.

The thing about Short Cuts, he said, was that as a class they didn’t feel it was a text with any real, well, merit.

I nodded. I asked him to elaborate, and he said, Well, it was all a bit ABC, wasn’t it? A bit, if I would forgive the expression, Ladybird.

You mean Carver’s prose style is too sparse for you? I suggested.

He gave me a pitying smile then, a smile such as one might give a Good Samaritan kneeling by the side of the road. Short Cuts was ‘random’, he said, in fact, quite frankly, it was hopeless. Was there any real need to attenuate the discussion with adjectives?

I didn’t tell him at the time that I wasn’t particularly wedded to Carver either, that we could have switched horses at that stage in the term to something more traditional, Jane Eyre, perhaps, or Frankenstein. But something in that drawling voice, that proprietorial slouch against my doorframe, got through to me that afternoon. The sixth form, I decided, would do Carver whether they liked it or not.

~

But something peculiar happened that winter term.

But something peculiar happened that winter term.

I began to read about Raymond Carver. I read interviews, I read articles, I read the short story collections Cathedral and Where I’m Calling From, and What We Talk About When We Talk About Love, only then returning, with an ever-increasing sense of admiration and excitement, to the Robert Altman selection which is Short Cuts.

It wasn’t simply that, from a teaching point of view, Short Cuts is an extraordinary show-case of the possibilities of short story form, although the class did enjoy debating whether Carver’s exhortation in ‘On Writing’ to ‘Get in, get out. Don’t linger’, was a viable premise for any sort of effective story-telling. It wasn’t only that we ended up being intrigued by a lean prose style that Carver himself admitted arose from his becoming ‘a little nervous if he [found] himself within earshot of sombre discussions about formal innovation in fiction writing’.

Nor was it simply that there seemed, to all of us, to be something pleasing in the idea that a successful short story arose from an ability ‘to stand and gape at this thing or that thing – a sunset, an old shoe – in absolute and simple amazement’. In Short Cuts, we learned, ‘this thing…or that’ can be a clock (‘Neighbors’), a woman’s exposed thigh (‘They’re Not Your Husband’), a dog slinking behind a fence (‘Jerry and Molly and Sam’), or, most powerfully of all, a rock (‘Tell the Women We’re Going’).

All of those elements were, admittedly, extraordinary, and we began to be entertained, provoked and sometimes pulled up short by the power of what Michael Trussler calls the ‘transparent qualities [and] elliptical style’, of Carver’s short prose. Each story, deliberately selected for collation into the grand narrative of the Short Cuts 1994 film, is dense enough to bear a good deal of structural and tonal scrutiny; each, in its way, can be seen as a direct descendant of the medieval morality play – from the warning parable about envy and acquisition in the first story, ‘Neighbors’, through the cathartic breaking of bread at the end of ‘A Small, Good Thing’, to the terrifyingly bloody climax of ‘Tell the Women We’re Going’.

But the class were studying American Literature for another unit, and brought with them to lessons a contingent desire to view the stories as American. And, over time, what struck us most is that there is a devastatingly synoptic quality to Altman’s selection of Carver’s short stories: together, they represent a kind of anti-manifesto, a sly, insouciant set of cultural observations not about how Americans ought to live, but the consequences, as Andre Dubus asserts, of ‘how we live’.

Although the men and women at the centre of Short Cuts are distinctly twentieth century protagonists – waitresses, pharmaceutical salesmen, Vietnam veterans – there’s a sense that they are also emblems of something distinctively American. More than a touch of the old Calvinist belief in predestination emerges in the behaviour of characters like Bill and Arlene Miller, who covet the more luxurious apartment next door in ‘Neighbors’. From their early fixation on ‘the sunburst clock’ and ‘the bottle of Chivas Regal’, the Millers’ excitement at their neighbours’ apartment becomes almost transgressive, with Bill finding himself ‘stepping into a brassiere and a pair of panties’ belonging to Harriet, and Arlene coming back from the apartment one day, ‘with lint clinging to her sweater’ and ‘the colour high in her cheeks’.

The luxury apartment challenges their imaginations and unsettles their identities until, at the end, the reader is left with the sense that they intend to appropriate it at any cost. ‘Perhaps they won’t come back’, suggests Arlene. Then, a moment later, ‘Or perhaps they’ll come back, and – ’

The ellipsis has the effect which Carver himself applauds in ‘On Writing’, when he demands that writers not only choose ‘the right words’, but use ‘the right punctuation’, so that the overall effect is, in the words of Isaac Babel, ‘like an iron that pierces the heart’. What, exactly, will happen when the Stones return to take back what is theirs?

Andrew Levine asserts, in The American Ideology: A Critique, that there is a distinct connection between material prosperity and the early Dutch, French and English settlers’ belief in predestination: ‘As success in one’s calling does normally issue in prosperity…prosperous workers [are seen as]…manifesting some inner grace’. And this desire to appropriate and cultivate property as a sign of prosperity, and, by extension, a sort of grace, is examined again in the second story, ‘They’re Not Your Husband’. Like many of the protagonists in Short Cuts, ‘Earl Oberman was between jobs as a salesman’, and it is his wife, Doreen, who has ‘gone to work nights as a waitress’, who therefore becomes the only sort of property her husband has. When Earl overhears ‘two men in business  suits’ appraising Doreen at the diner, and observing that only ‘jokers’ like ‘their quim’ as fat as Doreen, he begins to see his wife as the other men do, bending over the freezer to display ‘thighs that were rumpled and gray and a little hairy…with veins which spread in a beserk display’. The implied social and sexual judgement conferred upon the unemployed Earl is evident: his wife is derelict property and, in his pursuit of a more luxurious female ‘product’ by which to define himself, Earl buys a bathroom scale, and tells Doreen to ‘quit eating’, bullying her until she is so thin that she becomes ‘pale [and] spent more time in bed’. Suddenly, Earl has become what Chief Standing Bear of the Lakota tribe described at Wounded Knee in 1891 as the terrible ‘transforming hand’ of the white colonial man.

suits’ appraising Doreen at the diner, and observing that only ‘jokers’ like ‘their quim’ as fat as Doreen, he begins to see his wife as the other men do, bending over the freezer to display ‘thighs that were rumpled and gray and a little hairy…with veins which spread in a beserk display’. The implied social and sexual judgement conferred upon the unemployed Earl is evident: his wife is derelict property and, in his pursuit of a more luxurious female ‘product’ by which to define himself, Earl buys a bathroom scale, and tells Doreen to ‘quit eating’, bullying her until she is so thin that she becomes ‘pale [and] spent more time in bed’. Suddenly, Earl has become what Chief Standing Bear of the Lakota tribe described at Wounded Knee in 1891 as the terrible ‘transforming hand’ of the white colonial man.

Ironically, as he coerces his exhausted wife into losing more weight, Earl continues to hang around the diner, ‘watching and listening carefully’ for other men’s approbation, until even Doreen herself, when asked about him, can only say, ‘He’s a salesman’, with the admission that ‘He’s my husband’ coming only after a piercingly placed full-stop. The moment is tellingly underscored by her leaving ‘an unfinished chocolate sundae’ on the counter near her husband as the story closes.

The desolating effects of greed increase in ‘Jerry and Molly and Sam’, as husband Al, overburdened by a large family, ‘a cushy, two-hundred-a-month place’ and a demanding mistress fails to appease his domestic problems by ‘laying off’ the family dog, Suzy. And in ‘Tell the Women We’re Going’, Jerry, who has worked hard to acquire a family and ‘the house on the hill…’ is nonetheless goaded into homicidal mania by a barman’s taunts about whether he is ‘getting any on the side’. As he and his friend Bill subsequently pursue two girls on bicycles, even Jerry’s language becomes unsettlingly acquisitive: ‘I’ll take the brunette. The little one’s yours.’ And, as Bill observes in the final paragraph:

[…he] never knew what Jerry wanted. But it started and ended with a rock. Jerry used the same rock on both girls, the one called Sharon and the one that was supposed to be Bill’s.

Carver’s use of close third narrative perspective allows readers a devastating glimpse into the mind of the more passive Bill, who, even as he recounts the murder of the two women, seems latently wistful. ‘The other one’ is remembered only in terms of a missed opportunity for possession. She was ‘the one that was supposed to be Bill’s’.

The most interesting discussions about Short Cuts arose after we had finished the collection and were trying to see the selected stories as part of a coherent whole, a grand narrative composed from a series of fragments, like a Cubist portrait or, perhaps, a montage by the post-modern photographer Barbara Kruger. The boys had by then acquired a working knowledge of American history, from the original ‘purchase’ of Manhattan by the Dutch, through the expansionist ideology of Manifest Destiny, to the Battle of Little Big Horn and the Massacre at Wounded Knee in 1891. They could see by then, for example, that Donna’s insistent ambitions to move out West to Portland in ‘Vitamins’ is an echo of a well-established pioneering notion, that as the poet Louis Simson put it, ‘the end of America’ is only found when ‘we…look at the Pacific’.

Of course, it was Sam James in the end who pointed out that Altman’s selection and sequencing of Carver’s stories could be seen to echo the whole tragic arc of American expansionism. When I asked him to clarify, he shrugged. It begins with envy, he said, with the dispossessed and the disinherited, and their desire to make their mark on something which isn’t actually theirs.

And where, I asked, him, does it end?

And with a flash of that old school-boy swagger, he said, Well, that’s obvious, isn’t it? It’s like Jerry. It ends with a rock. It ends, he said, in blood.

Of all Carver’s assembled greatnesses, we agreed that his genius really does lie in the endings of these stories. The characters in Short Cuts are all in crisis, and what Carver deliberately does not offer in any of these stories is any redemptive sense of closure. In fact, the chaos seems to persist beyond the closing images of characters leaning against locked doors, or of an unfinished sundae left abandoned on a counter. At the end of ‘Vitamins’, we are left simply with ‘things’ which ‘kept falling’, or, in ‘Will You Please Be Quiet, Please’, with a man ‘turning, and turning’ towards his adulterous wife, ‘amazed at the tremendous changes he felt moving over him’.

If Andre Dubus was right, and short stories are, indeed, ‘the way we live’, then what Short Cuts seems to suggest is that as we sow, so shall we reap. And, as America heads towards the 2016 presidential election, it would surely do well to remember Carver’s insights about American culture. The iron which pierces the heart is this: what begins with greed and acquisition will end with blood.

It will end, as Sam James pointed out, with a rock.

One thought on “2016 Competition Winner”

Comments are closed.